Release Date: 12 June 1916

Writer/Director: Charles Chaplin

Duration: 24 mins

With: Eric Campbell, Edna Purviance, Lloyd Bacon, Albert Austin, James T. Kelley, John Rand, Leo White, Frank J. Coleman

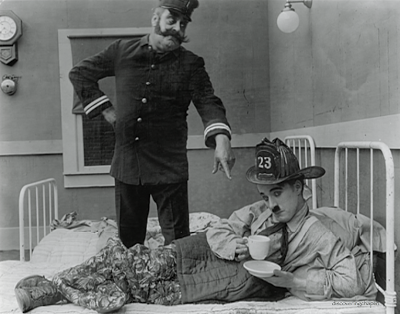

Story: The Tramp has a job, as an incompetent fireman at Station 23. Caught up in an insure-and-burn scheme, he has to rescue fire chief’s intended from the flames…

Production: Charlie Chaplin’s second short for Mutual continued his focus on gags and situations—as the title suggests, Chaplin plays the role of an inept firefighter—but he failed to add any additional depth to his character. Perhaps he felt he needed to find his feet making new films for a new studio in unfamiliar circumstances before he could turn his attention to further developing his art? As it is, The Fireman is a gag-laden short that is richly amusing if not emotionally enriching. According to John McCabe, Chaplin drew inspiration from simply walking past a local Los Angeles fire station near to the Mutual studio one day and imaging himself as a fireman, a man completely at the mercy of the demands of the fire alarm bell. It was enough to see him embark upon making the short, even without a fully worked out scenario, as was increasingly becoming his habit. That approach might explain the somewhat disjointed, episodic nature of The Fireman.

This is a short more in the Keystone style, with Eric Campbell as the hopeless fire chief who gets caught up in an insure-and-burn caper so he can wed a businessman’s daughter (played by Edna Purviance). His plan falls apart, however, when the ever-heroic Charlie comes to the rescue after he spots Edna (whom he’s also in love with) trapped in the burning building. There is something of the later Harold Lloyd ‘thrill pictures’ in the climax as Chaplin (or maybe a stunt double, see ‘Trivia’) scales the ladder to come to Edna’s rescue. Meanwhile, Leo White’s house is also burning down, but nothing he does seems to engage the interest of the fire department.

Filming for The Fireman took place at a real fire station—Fire Station #29, located at 158 South Western, which had opened just three years before (it only closed in 1988, making it potentially the Los Angeles fire station that was in continuous use the longest). This decision gave the short some very high production values, as Chaplin was able to fully utilise the premises and the (horse-drawn) fire trucks stored there—presumably all subject to them being withdrawn from the film if there were an emergency call out.

In addition to the fire station, real fires mounted by the production team at two separate condemned houses added further spectacular production value. Scenes of Chaplin rushing to get to the fires, with the fire fighter crew hanging on to the buggy for dear life, recall some of the old Keystone rough-and-tumble chases from two years before. Even when they reach the site of the fire, the firemen insist on limbering up before they dare tackle the blaze…

Despite all this action, there is room in the short for some quieter comic moments, such as when Charlie uses the fire engine’s boiler as a makeshift coffee urn, dispensing coffee and cream from its taps, and a scene in which the naïve fireman attempts to brush down the department’s horses using a dainty feather duster. These were characteristic comedy moments, but the relationship with Edna is not advanced much (attaching her to Eric Campbell’s villain made that difficult) and so the opportunities for any kind of heart-tugging pathos are limited.

Despite all this action, there is room in the short for some quieter comic moments, such as when Charlie uses the fire engine’s boiler as a makeshift coffee urn, dispensing coffee and cream from its taps, and a scene in which the naïve fireman attempts to brush down the department’s horses using a dainty feather duster. These were characteristic comedy moments, but the relationship with Edna is not advanced much (attaching her to Eric Campbell’s villain made that difficult) and so the opportunities for any kind of heart-tugging pathos are limited.

Upon the release of The Fireman, Chaplin received a letter in reaction to the short from a fan that brought him up short (according to biographer John McCabe). The mid-westerner wrote: ‘I have noticed in your last picture a lack of spontaneity. Although the picture was unfailing as a laugh-getter, the laughter was not so round as in some of your earlier work. I am afraid that you are becoming a slave to your public, whereas in most of your pictures the audience were a slave to you…’ It seemed to Chaplin that the complaint was a valid one—he was in danger of resting on his laurels, and churning out material that could have been made at Keystone or even at Essanay was not enough. He would have to strive to deepen both his character and his filmmaking techniques if he was to stay one step ahead of his fans, giving the public not what they wanted but what they didn’t know they needed.

The latest addition to the Chaplin company at Mutual was James T. Kelley (born in Castlebar in July, 1854 and sometimes billed as ‘Kelly’), an Irish-born performer who had a degree of stage and dance experience, but on film often played elderly inebriates. His earlier films included some Edison credits in 1897: Bowery Waltz (aka Apache Dance) and Charity Ball. He was seen alongside Louise Fazenda in the Universal short The Battle of the Nations in 1914. Kelley had appeared alongside Chaplin before in A Night in the Show and in Police, but he’d really make his mark during the Mutual period. He was the elderly elevator operator in The Floorwalker, a past his prime fireman in The Fireman, and later an out-of-shape bellhop in The Cure and he played two roles in the Chaplin classic The Immigrant. He worked with Chaplin right through the Mutual period, including roles in The Pawnshop, The Vagabond, A Dog’s Life, The Count, The Rink, and Easy Street. He also worked with Harold Lloyd, appearing in his 1921 comedy Among Those Present right through to the feature Safety Last (1923). Later in the 1920s he appeared in a variety of Western films, including Man Rustlin’ (1926) and Men of Daring (1927). He died in 1933 at the age of 79 in New York City.

Along with his newfound popularity, Chaplin had to face a new problem: film piracy. In the earliest days of movie distribution, films were released across the US via local ‘film exchanges’ in an often haphazard manner. Films were considered disposable, unlikely to last (either physically or in the memory of audiences) beyond the projected 90-day life of a standard print. It was easy for unscrupulous practitioners to obtain copies of the newest Chaplin short and strike their own copy, which they then leased out to cinemas pocketing the theatrical screening fee that should have gone back to the studios, whether Keystone, Essanay, or—from May 1916—Mutual, none of whom seemed too interested in protecting their property. (French filmmaker George Méliès, a special effects and filmmaking pioneer in his own right, especially suffered from US piracy of his works).

One example was the completely unauthorised ‘Chaplin Film Company’ that actually had an office on West 45th Street in Manhattan. It was Keystone investor Charles Baumann who discovered it following a tip-off. This unofficial distributor was well-stocked with ‘dupes’, unofficial duplicate prints, copies of the most popular Chaplin shorts and at this point—in the summer of 1915—was making great money from distributing Chaplin’s Dough and Dynamite. Now aware of the transgression, Keystone went to court and had the whole operation shut down. That, however, was just one of many ‘dupe’ distributors in action, many of them not daft enough to open a shop front in a major Manhattan thoroughfare.

One step beyond that kind of direct theft was the ‘bogus Chaplins’. These weren’t films featuring Chaplin impersonators and imitators (already covered here: In The Park), but movies made up of extracts or outtakes from Chaplin’s work that was re-edited to make a ‘new’ Chaplin release. One such was The Perils of Patrick, modelled after Pathe’s The Perils of Pauline (at least as far as the title went), a serial made up of much of Chaplin’s Keystone footage. It didn’t help their case that both Keystone and Essanay (see Burlesque on Carmen) were not above similar activity themselves.

The effort that went in to creating these ‘bogus’ Chaplin shorts was often ingenious. Rather than put their efforts into creating original works of their own, several would-be filmmakers took the opportunity of Chaplin’s stratospheric popularity to ride on the innovative comedian’s coat tails. Among them were Bronx-born duo Jules Potash and Isadore Peskov who took Chaplin’s The Champion (an Essanay release), removed the backgrounds and replaced them with an unlikely undersea world, itself lifted directly from Herbert Brenon’s film Daughter of the Gods. The resulting uncomfortable mash-up was released (through their New Apollo Feature Film Company) under the title Charlie Chaplin in a Son of the Gods, a film which contrived to show the Tramp visiting King Neptune’s court and there encountering Keystone-style bathing beauty mermaids. This film was brazenly screened at the 14th Street Crystal Palace theatre in New York, a regular venue for Chaplin’s legitimate products. Having succeeded with that release, Potash and Peskov were soon at it again with Charlie in the Harem and the predictive Charlie in the Trenches (itself a working title for the later Shoulder Arms, 1918). As Chaplin did not own the copyright to his early works, there was little he could do about such disgraceful behaviour.

Others were inspired to follow the example of Potash and Peskov: after all, there was money in them thar films. The Seiden brothers—Joseph and Jacob—operated out of Chicago (Chaplin’s onetime Essanay stamping ground) and released a Chaplin knockoff under the title The Fall of the RummyNuffs (a supposed pun on the Russian Romanovs, then in the news). As well as adapting original footage, particularly enterprising film pirates would hire Chaplin lookalikes in order to create ‘new’ material to expand the length of the films (this lead to the full-blown craze for Chaplin impersonators such as Billy West). By this time, Chaplin was signed to First National (in 1917), and his legal officer Nathan Burkan launched a concerted effort to rid cinemas of these ‘bogus’ Chaplin films, including such titles as The Dishonour System (a two-reeler) and One Law for Both. Targets he attacked included not only the filmmakers themselves, but also the laboratories that developed the film, those who made the posters for the bogus movies, and those who screened them—all in an attempt to seek some form of financial redress. ‘Several suits will be started against each and every exhibitor in this and other cities for exhibiting spurious Charlie Chaplin pictures,’ said Burkan. At First National, Chaplin developed an innovative way of authenticating his films to counter such piracy, but we’ll cover that when the blog reaches Chaplin’s First National releases.

Others were inspired to follow the example of Potash and Peskov: after all, there was money in them thar films. The Seiden brothers—Joseph and Jacob—operated out of Chicago (Chaplin’s onetime Essanay stamping ground) and released a Chaplin knockoff under the title The Fall of the RummyNuffs (a supposed pun on the Russian Romanovs, then in the news). As well as adapting original footage, particularly enterprising film pirates would hire Chaplin lookalikes in order to create ‘new’ material to expand the length of the films (this lead to the full-blown craze for Chaplin impersonators such as Billy West). By this time, Chaplin was signed to First National (in 1917), and his legal officer Nathan Burkan launched a concerted effort to rid cinemas of these ‘bogus’ Chaplin films, including such titles as The Dishonour System (a two-reeler) and One Law for Both. Targets he attacked included not only the filmmakers themselves, but also the laboratories that developed the film, those who made the posters for the bogus movies, and those who screened them—all in an attempt to seek some form of financial redress. ‘Several suits will be started against each and every exhibitor in this and other cities for exhibiting spurious Charlie Chaplin pictures,’ said Burkan. At First National, Chaplin developed an innovative way of authenticating his films to counter such piracy, but we’ll cover that when the blog reaches Chaplin’s First National releases.

Another pressing problem that Chaplin faced in the summer of 1916 was the question of his willingness (or otherwise) to fight for his country—Great Britain—in the then-unfolding ‘Great War’, better known today as the First World War. In 1914, when war was first declared with Germany, Chaplin had decided to stay in the US rather than return home to do his bit for ‘King and Country’ (as the misguided patriotic cry had it). By the time he was at Mutual, just as the war was kicking into a higher gear in the summer of 1916, it became public that Chaplin’s Mutual contract actually contained a clause that would actively prevent him from ‘joining up’ in the British army as he was considered to be such a valuable ‘commodity’ to the company.

This created something of a backlash with some popular sentiment portraying Chaplin as a coward who was actively avoiding conscription (the ‘draft’ in the US) of ordinary citizens to serve in the army that was ensnaring much of his home country audience. The comedian began to receive letters from soldiers containing white feathers, long a symbol of cowardice in the face of war, and a handful of cinemas back in Britain refused to screen any further Chaplin films due to his non-participation in the war. At the same time, Chaplin received letters from other soldiers, many serving at the frontlines in France, pleading with him to continue making the ‘funny’ films that made them laugh and raised their morale in the face of deadly danger. Some in the ‘top brass’ of the British army actually came to regard Charlie Chaplin’s filmmaking to be a much more important contribution to the British war effort and to raising morale both among soldiers and on the ‘home front’ than any effort he could personally make by picking up a rifle.

According to Chaplin biographer David Robinson, the campaign to harass Chaplin due to his seeming avoidance of war service had been instigated by Lord Northcliffe, the publisher of Britain’s Daily Mail newspaper. From the spring of 1916 the paper had been carrying disparaging comments about Chaplin’s failure to sign up with Britain’s armed forces, highlighting the clause in his Mutual contract that apparently prevented him from returning to his homeland for the duration of the conflict in case he should be conscripted to fight. ‘We have received several letter protesting against the idea of [anyone] making a profit on the exhibition in this country of a man who binds himself not to come home to fight for his native land,’ said the newspaper.

According to Chaplin biographer David Robinson, the campaign to harass Chaplin due to his seeming avoidance of war service had been instigated by Lord Northcliffe, the publisher of Britain’s Daily Mail newspaper. From the spring of 1916 the paper had been carrying disparaging comments about Chaplin’s failure to sign up with Britain’s armed forces, highlighting the clause in his Mutual contract that apparently prevented him from returning to his homeland for the duration of the conflict in case he should be conscripted to fight. ‘We have received several letter protesting against the idea of [anyone] making a profit on the exhibition in this country of a man who binds himself not to come home to fight for his native land,’ said the newspaper.

By the following year, the rhetoric had escalated, with an editorial (probably dictated by Northcliffe himself) running in the Weekly Dispatch that castigated the comedian: ‘Charles Chaplin, although slight built, is very firm on his feet, as is evidenced by his screen acrobatics. … During the 34 months of the war it is estimated [that] he has earned well over £125,000. … Chaplin can hardly refuse the British nation both his money and his services. … He is under the suspicion of regarding himself as specially privileged to escape the common responsibilities of British citizenship. … It is Charlie’s duty to offer himself as a recruit.’ Other papers, including the Daily Express, joined the calls against Chaplin’s non-participation.

Eventually, the star was forced into issuing a statement on the situation to the press: ‘I am ready and willing to answer the call of my country to serve in any branch of the military service at whatever post the national authorities may consider I might do the most good,’ said Chaplin. ‘But, like thousands of other Britishers, I am awaiting word from the British Embassy in Washington.’ He went on to highlight his financial investments in the war effort and the fact that he’d registered for the draft (drawn on a random lottery basis) in the United States.

Sydney was drawn into the fuss, too, having to confirm that he was over the exemption age of 31—the suspicion was that he’d been singled out simply because he was Chaplin’s (half) brother. The active campaign against Chaplin only came to an end, according to Robinson, when the actor presented himself at a recruiting office but was turned away for being underweight!

Sydney was drawn into the fuss, too, having to confirm that he was over the exemption age of 31—the suspicion was that he’d been singled out simply because he was Chaplin’s (half) brother. The active campaign against Chaplin only came to an end, according to Robinson, when the actor presented himself at a recruiting office but was turned away for being underweight!

According to Peter Ackroyd’s biography of Chaplin the comedian wrote back to one soldier correspondent that he was ‘sorry my professional demands do not permit my presence in the Mother Country.’ According to another friend, Chaplin had expressed his utter horror of war in these terms: ‘Not for me! I’d have gone to jail rather than have gone into it. I’d have gnawed off my fist rather than get into that sort of thing.’ These sentiments perhaps reflected Chaplin’s growing pacifist feelings rather than any cowardice in his nature. Later Chaplin would tackle the subject directly in 1918’s Shoulder Arms and would tour the US (where he was greeted by record-breaking crowds) promoting the purchase of war bonds. — Brian J. Robb

Trivia: It doesn’t appear to be Chaplin driving the horse-drawn fire truck from the station, more like Eric Campbell (based on his size) or an anonymous stuntman. Similarly, the dummy figure that Chaplin carries down during the rescue scene has much darker hair than the blonde Edna Purviance, who he is supposedly rescuing!

The Contemporary View: ‘There is an abundance of the rough comedy which secures laughs. The best laughs are when the prop engine falls apart. The rescue of the girl from the top storey is a good hit, also the general business around the firehouse.’—Variety, June 1916

Verdict: The Fireman is a throwback to Keystone and Essanay slapstick, but Chaplin was capable of more sophisticated comedy.

Next: The Vagabond (10 July 1916)

Available Now!

CHARLIE CHAPLIN: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION

An 80,000 word ebook chronicle of Chaplin’s early films from Keystone (1914) and Essanay (1915), based on the blog postings at Chaplin: Film by Film with 20,000 words of supplemental biographical essays.

Also available at Kobo, Nook, Apple, Scribd and other ebook outlets.

Pingback: The Floorwalker (15 May 1916) | Chaplin: Film by Film