Release Date: 11 April 1947

Written & Directed by Charlie Chaplin

Duration: 124 minutes

With: Martha Raye, William Frawley, Marilyn Nash, Isobel Elsom, Barbara Slater, Fritz Leiber, Mady Correll Robert Lewis, Charles Evans

Story: During an economic depression, a former bank clerk turns to seduction and murder to keep the money flowing…

Production: There’s a question of authorship lingering in the development of Monsieur Verdoux (1947), the film that finally saw Charlie Chaplin dispense with the Tramp character he’d been playing (in several variants) since 1914, once and for all. There is no doubt the idea for a film based upon the Landru story originally came from Orson Welles, who’d made his mark in Hollywood in 1941 with Citizen Kane. What happened beyond that was long a matter of debate between Chaplin and Welles.

Landru was notoriously known as ‘Bluebeard’. Between the end of 1915, just as Chaplin was enjoying his first fame, and early 1919 (between the release of Chaplin’s Shoulder Arms in October 1918 and Sunnyside in June 1919), Parisian Henri Landru killed seven women (his total may stretch to 10, including at least three people he may have killed earlier). As a serial killer, Landru’s modus operandi was romance—he would seduce women, preferably rich women, only to then kill them, most often by strangulation. Following a trial, Landru was executed by guillotine in February 1922, shortly before Chaplin’s Pay Day reached movie screens. If nothing else, the serial killer and screen clown were contemporaries.

Landru was notoriously known as ‘Bluebeard’. Between the end of 1915, just as Chaplin was enjoying his first fame, and early 1919 (between the release of Chaplin’s Shoulder Arms in October 1918 and Sunnyside in June 1919), Parisian Henri Landru killed seven women (his total may stretch to 10, including at least three people he may have killed earlier). As a serial killer, Landru’s modus operandi was romance—he would seduce women, preferably rich women, only to then kill them, most often by strangulation. Following a trial, Landru was executed by guillotine in February 1922, shortly before Chaplin’s Pay Day reached movie screens. If nothing else, the serial killer and screen clown were contemporaries.

Subtitled ‘A Comedy of Murders’ (which had been an overall working title), the idea for a Landru film originated with Welles, with Chaplin set to star for the director. Welles regarded Chaplin as a better actor than he was a director, offering The Great Dictator as evidence of his old-fashioned and rather simplistic approach to filmmaking. It is true that Chaplin was no great stylist behind the camera, but then he was probably more focused on what he was doing, as the Tramp, in front of the camera than on finding an innovative way of filming it. Having agreed to star, Chaplin had second thoughts and reneged on their arrangement.

It appears Chaplin was concerned about playing a leading role in another director’s film—he was certainly not an actor-for-hire, and was worried that there would be inevitable clashes between two such titanic personalities as he and Welles. Chaplin offered to buy the Landru script, then entitled ‘The Ladykiller’, from Welles, and needing the money—as he often did from the mid-1940s onwards when he was pursuing his independent productions—Welles agreed to sign over all rights to the Landru story concept to Chaplin.

For his part, Chaplin had claimed the Landru idea originally came to him from Welles as a possible documentary project. Instead, Chaplin saw the comic possibilities in playing the role of a suave, sophisticated murderer (which Landru almost certainly was not in real life). He paid off Welles with $5,000 and a ‘story by’ credit on the resulting film. The only part of the film that Welles specifically claimed credit for was an early scene of Verdoux tending to his roses in the garden while in the background a chimney belches ominous black smoke…

By the fall of 1942 Chaplin was openly talking about his next project, with critic and writer Alexander Woollcott recalling a dinner during which the director acted out virtually every scene from the planned movie. During the writing of the script in 1943, Chaplin paused to marry the now 18-year-old Oona O’Neill in June (he was 52). In 1944 there was further delay when the Joan Barry case enveloped Chaplin (see below), dragging him into court and all but monopolising his time and focus. As a result, Chaplin didn’t have a completed shooting script for Monsieur Verdoux until 1946, and shooting finally took place between May and September that year.

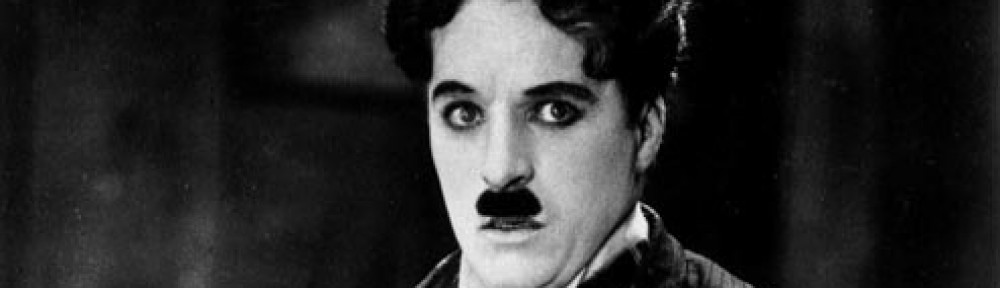

To play a role very far removed from his internationally recognised Tramp, Chaplin decide it was necessary to dramatically change his entire appearance . He spent six weeks growing a genuine moustache, wax-tipped in the approved French manner. He allowed the grey that featured in his natural hair to show through for the first time on screen, and he dressed in exquisite suits, complete with a range of hats and canes. As Henri Verdoux, Chaplin was, to all intents-and-purposes, the most polite and dapper ‘lady killer’ in town.

To play a role very far removed from his internationally recognised Tramp, Chaplin decide it was necessary to dramatically change his entire appearance . He spent six weeks growing a genuine moustache, wax-tipped in the approved French manner. He allowed the grey that featured in his natural hair to show through for the first time on screen, and he dressed in exquisite suits, complete with a range of hats and canes. As Henri Verdoux, Chaplin was, to all intents-and-purposes, the most polite and dapper ‘lady killer’ in town.

Having got away with his comic portrayal of Hitler in The Great Dictator, his comedy murder script ran into unexpected censorship problems the like of which Chaplin had never really dealt with before. The Breen Office made such strenuous objections to his screenplay [see Trivia] that Chaplin threatened to make the film but not release it in American. ‘I can get all I need [financially] to make a profit from foreign distribution alone,’ he claimed. Whether this threat gave him greater leverage with the censors is unclear, but he persisted with them engaging in their seemingly endless process of focusing on minutia like Verdoux’s questionable tone with the Priest, as well as ‘big picture’ concerns such as suggestions of ‘illicit sex’.

When it came to finally shooting the film, Chaplin hired director Robert Florey (who had carried out his own cinematic murder spree in 1931’s Murders in the Rue Morgue) as an associate director and an informal advisor on all-things French, which Chaplin went to great pains to get right. It is possible this move suggests a lack of confidence in Chaplin especially when it came to directing himself in such a sustained character piece, complete with more dialogue than he’d ever spoken on screen before. Florey became an all-round assistant, directing some of the non-Chaplin scenes, casting some of the smaller roles, and generally helping Chaplin achieve his vision.

Chaplin as Verdoux adopts a variety of aliases to access his various ‘wives’. At home waits his real wife, Mona (Mady Correll), looking after their young son, Peter. Also waiting is Lydia Florey (Margaret Hoffman), who believes Verdoux to be an engineer who has been travelling for three months. She’s the first victim we see Verdoux eliminate, only to make use of her funds the next morning. In his sights as his next victim is Marie Grosnay (Isobel Elsom) who comes to view his for-sale house. Also in play is the alarming Annabella (Martha Raye), who believes Verdoux to be a sailor, Captain Bonheur. She proves somewhat indestructible, surviving all of Verdoux’s attempts to remove her, whether through poisoned wine or the more direct approach of tossing her overboard from his boat. It is Annabella who ultimately thwarts his attempt to marry Grosnay. Also featured is ‘The Girl’, a young woman Verdoux finds on the street—a ‘derelict’, and in no way a prostitute, thanks to film censor intervention. He plans to try out his poison on her, but her commitment to looking after her now deceased injured war veteran husband stays Verdoux’s hand. She ultimately makes good in life as the wife, or perhaps companion, to an arms dealer making a fortune from war. That’s the core of Chaplin’s take on Verdoux—his individual acts are immoral, but society’s collective acts of war and destruction are seen as patriotic. It was a view that would bring Chaplin further trouble later.

Chaplin as Verdoux adopts a variety of aliases to access his various ‘wives’. At home waits his real wife, Mona (Mady Correll), looking after their young son, Peter. Also waiting is Lydia Florey (Margaret Hoffman), who believes Verdoux to be an engineer who has been travelling for three months. She’s the first victim we see Verdoux eliminate, only to make use of her funds the next morning. In his sights as his next victim is Marie Grosnay (Isobel Elsom) who comes to view his for-sale house. Also in play is the alarming Annabella (Martha Raye), who believes Verdoux to be a sailor, Captain Bonheur. She proves somewhat indestructible, surviving all of Verdoux’s attempts to remove her, whether through poisoned wine or the more direct approach of tossing her overboard from his boat. It is Annabella who ultimately thwarts his attempt to marry Grosnay. Also featured is ‘The Girl’, a young woman Verdoux finds on the street—a ‘derelict’, and in no way a prostitute, thanks to film censor intervention. He plans to try out his poison on her, but her commitment to looking after her now deceased injured war veteran husband stays Verdoux’s hand. She ultimately makes good in life as the wife, or perhaps companion, to an arms dealer making a fortune from war. That’s the core of Chaplin’s take on Verdoux—his individual acts are immoral, but society’s collective acts of war and destruction are seen as patriotic. It was a view that would bring Chaplin further trouble later.

Hanging over the entire period that Charlie Chaplin was working on the script for Monsieur Verdoux was the bizarre Joan Barry case. Chaplin had met Barry in between his relationships with Paulette Goddard and Oona O’Neill. She was an aspiring actress who’d come to Hollywood intent upon becoming a film star. She and Chaplin met following one of his regular, well-populated weekend tennis parties. They dined together at Romanoff’s, and the following day took a trip to Santa Barbara. This was in 1941, when Chaplin was 52, while Barry was 30 years younger. In his 1964 autobiography, Chaplin bizarrely described Barry as ‘a big handsome woman of 22, well built, with upper regional domes immensely expansive and made alluring by an extremely low décolleté summer dress which … evoked my libidinous curiosity.’ In the aftermath of the scandal that unfolded, Chaplin maintained that Barry had pursued him romantically; however it was instigated, the pair certainly had a stormy, short-lived relationship.

As had been his habit, Chaplin justified his interest in yet another young woman thorough his work—he had her screen tested for a proposed film of a 1937 Paul Vincent Carroll play entitled Shadow and Substance. By June, Barry was under contract to Chaplin, and in time honoured fashion he sent her out for acting lessons. Barry claimed it was only at this point that she gave in to Chaplin’s demands for a sexual relationship.

Things very quickly unravelled. Barry became a nuisance, whose drinking was getting out of control making her erratic behind the wheel of any automobile. She would arrive at Chaplin’s home at all hours of the day or night demanding his attention, often drunk. Property was damaged, including broken windows. ‘Finally, she got so obstreperous that when she called in the small hours, I would neither answer the phone nor open the door to her,’ wrote Chaplin in My Autobiography (1964). ‘Overnight, my existence became a nightmare…’

It became clear that Barry had not been attending the acting lessons that Chaplin was paying for, and when he called her on it, she denied any ambitions to become an actress. Her interest in Chaplin seemed purely financial as she demanded $5,000 in order to return to New York with her mother. Chaplin claims he agreed, and tore up her contract upon paying her off. Barry told a different story, claiming to have been pregnant and to have been sent by Chaplin for an abortion in New York (then a criminal offence). Upon arriving in the city, Barry apparently decided not to go through with the procedure that she claimed Chaplin had paid for. Back in Los Angeles, Chaplin and an associate seemingly made sure she underwent the procedure this time.

That was thought to be the end of the matter, and while things went quiet for a while, Joan Barry never really went away. By the end of 1942, she was back to trouble Chaplin once more. A couple of days before Christmas, Barry broke into Chaplin’s house, wielding a gun and threatening suicide. Apparently, with Chaplin’s willing acquiescence, she then stayed the night. She was back a week later, like a stalker, and this time Chaplin took her to the police. That apparent warning shot wasn’t enough to make her change her behaviour and she was found the following night on Chaplin’s grounds, once again armed.

That was thought to be the end of the matter, and while things went quiet for a while, Joan Barry never really went away. By the end of 1942, she was back to trouble Chaplin once more. A couple of days before Christmas, Barry broke into Chaplin’s house, wielding a gun and threatening suicide. Apparently, with Chaplin’s willing acquiescence, she then stayed the night. She was back a week later, like a stalker, and this time Chaplin took her to the police. That apparent warning shot wasn’t enough to make her change her behaviour and she was found the following night on Chaplin’s grounds, once again armed.

Through a media-savvy friend Barry planted a story in the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner that she had been ‘dumped’ by Chaplin following a romance and would kill herself as a consequence. The newspapers referred to Barry as ‘a Titian-haired protégée of Chaplin’. A subsequent overdose of barbiturates was described by the attending physician as a ‘simulated suicide attempt’. The police charged the seemingly homeless Barry with vagrancy. Sentenced to 90 days in prison, she was told the term would be suspended as long as she left town and stayed away for two years.

Joan Barry didn’t stay away from Charlie Chaplin for long. By May 1943, she was back at his home claiming once more to be pregnant. Following an unsatisfactory confrontation, Barry began to communicate with Hearst columnist Hedda Hopper, who was only too willing to listen to malicious gossip about the ‘Communist Charlie Chaplin’. Barry continued to harass Chaplin throughout the summer of 1943, even as her pregnancy began to be noticeable. Fearing for his life, Chaplin attempted to console Barry, but this only served to encourage her.

That same month, Barry’s mother Gertrude filed suit against Chaplin naming him as the father of her daughter’s unborn child and demanding a payment of $2,500 per month and $10,000 for ‘pre-natal costs’. Chaplin flatly denied paternity and refused an offer of a quick settlement that would see him pay Barry off. The scene was set for a sensational court action.

Around this time Chaplin married Oona O’Neill, who was 36 years his junior. It was his fourth wedding, if that with Paulette Goddard was counted. What followed was a ‘phoney peace’, as the law took its time to come to terms with the Joan Barry case. At the start of October, Barry gave birth to the child that she claimed was Chaplin’s. The following February Chaplin was formally charged under the Mann Act which forbade the crossing of State lines for immoral purposes, something he was said to have done by buying Barry a train ticket to New York. A prison sentence of at least 20 years awaited Chaplin if he was found guilty by a Federal grand jury.

The use of the Mann Act in this way by prosecutors was targetted against those (like Chaplin) who’d spoken out in favour of a ‘second front’ during the war to help relieve pressure on Russia; a similar prosecution had been considered against writer Theodore Dreiser for similar reasons, but was not ultimately progressed. Now, Chaplin was the target. One newspaper commentator even went so far as to claim that Chaplin might have been the victim of a ‘fascist clique in America’ in retaliation for his caricature of Hitler in The Great Dictator. The Washington Times-Herald opined that ‘this is persecution of Chaplin by the Federal government’.

The use of the Mann Act in this way by prosecutors was targetted against those (like Chaplin) who’d spoken out in favour of a ‘second front’ during the war to help relieve pressure on Russia; a similar prosecution had been considered against writer Theodore Dreiser for similar reasons, but was not ultimately progressed. Now, Chaplin was the target. One newspaper commentator even went so far as to claim that Chaplin might have been the victim of a ‘fascist clique in America’ in retaliation for his caricature of Hitler in The Great Dictator. The Washington Times-Herald opined that ‘this is persecution of Chaplin by the Federal government’.

The trial of Charlie Chaplin began on 21 March 1944, with the expected press and public hullabaloo. The event was a circus, with witnesses lining up to testify against Chaplin. The trial ended with Chaplin’s own evidence in which he denied all the charges. On 4 April, Chaplin was acquitted on all charges, but the screen clown’s reputation would never recover from the damage the public spectacle of a ‘morals’ trial had inflicted on him, combined with his well-known leftist political views.

That should have been the end of the Joan Barry affair, yet—bizarrely—it was not. At the end of the year, Chaplin faced a paternity case over Barry’s child. A trio of doctors stated that blood tests proved that the comedian could not possibly be the father of the child. Barry’s legal representative attacked Chaplin’s person and morals in an attempt to sway the jury, despite the established biological facts. Barry’s attorney Joe Scott impugned Chaplin’s character with epithets like ‘Cockney cad’ and ‘Piccadilly pimp’ (among others), while also calling attention to his London origins and failure to take up US citizenship. Chaplin complained to the judge: ‘I’ve committed no crime. I’m only human, but this man is trying to make a monster out of me.’ The trial ended in deadlock and was not resolved until the following spring when during another hearing where Chaplin did not appear, he was deemed—by a jury of 11 women and one man—to be responsible for the child that he could not have possibly biologically fathered.

It was an astonishing mind-boggling outcome, and Chaplin was forced to pay $75 each week (later raised to $100) to Barry’s daughter Carol Ann (until her 21st birthday) who was, furthermore, also legally allowed to use the name Chaplin. It was a bizarre travesty of justice, but Joan Barry’s relentless campaign of harassment appeared to have paid off. While the girl continued to receive payments, Barry herself didn’t ultimately benefit as she vanished into the American mental health care system of the 1950s. It was an entirely unsatisfactory end to an entirely unsatisfactory sequence of events that contributed to Chaplin’s eventual downfall in the US..

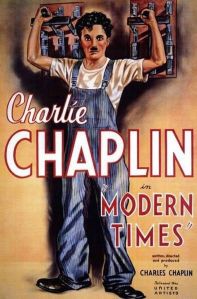

Chaplin had gambled with The Great Dictator and had won, now he gambled with Monsieur Verdoux and, misjudging both the times and the fallout from the Barry case, he lost. The film was a commercial failure, a fact that Chaplin’s longterm associate Henry Bergman had predicted. Bergman had been considered for a role, especially as Bergman considered himself to be Chaplin’s good luck charm. Chaplin, however, felt the actor looked too ill to participate—Begrman died in October 1946, prior to the release of Monsieur Verdoux. His final film appearance had been as the cafe proprietor in Chaplin’s own 1936 film Modern Times.

The subject matter alone should have been a red flag. In the years immediately following the conclusion of the Second World War audiences were in no mood for a tale of a serial murderer who almost gets away with it. Even more, they were not prepared to accept such a film from Charlie Chaplin, whose reputation had been sullied by the Barry affair and by allegations regarding his political views, some of which seeped into the film. Monsieur Verdoux raised questions about the connections between business and war, from which business can profit at the expense of lives.

On some posters for Monsieur Verdoux, a challenge was thrown out to audiences that had grown-up with the ‘old’ Charlie Chaplin, the knockabout Keystone Tramp: ‘Chaplin Changes!’ the poster declared, and then asked, pointedly, ‘Can You?’ Chaplin knew the film would be challenging to some audiences, and he expected critics to dislike it. At a press conference to launch the movie in New York in April 1947 he invited the attending reporters to ‘proceed with the butchery’. Many of the questions concerned what ‘message’ Chaplin was trying to communicate, and whether he felt audiences would be willing to follow him in this new, somewhat startling direction. Chaplin’s supposed ‘Communist sympathies’ were also queried, something he denied although he was happy to admit to having supported Russia as ‘a wartime ally’. The press conference rapidly became an inquisition with a free-for-all as journalists hurled questions to Chaplin about his nationality status, his income, and his refusal to fight for Britain in either of the World Wars. Getting back on topic, Chaplin was finally asked about his reaction to the reviews of his latest film: ‘Well, the one optimistic note is that they were mixed,’ said the screen clown.

On some posters for Monsieur Verdoux, a challenge was thrown out to audiences that had grown-up with the ‘old’ Charlie Chaplin, the knockabout Keystone Tramp: ‘Chaplin Changes!’ the poster declared, and then asked, pointedly, ‘Can You?’ Chaplin knew the film would be challenging to some audiences, and he expected critics to dislike it. At a press conference to launch the movie in New York in April 1947 he invited the attending reporters to ‘proceed with the butchery’. Many of the questions concerned what ‘message’ Chaplin was trying to communicate, and whether he felt audiences would be willing to follow him in this new, somewhat startling direction. Chaplin’s supposed ‘Communist sympathies’ were also queried, something he denied although he was happy to admit to having supported Russia as ‘a wartime ally’. The press conference rapidly became an inquisition with a free-for-all as journalists hurled questions to Chaplin about his nationality status, his income, and his refusal to fight for Britain in either of the World Wars. Getting back on topic, Chaplin was finally asked about his reaction to the reviews of his latest film: ‘Well, the one optimistic note is that they were mixed,’ said the screen clown.

There was a wave of hostility towards Monsieur Verdoux from the press critics, with James Agee in The Nation standing out against the tide. ‘Disregard virtually everything you may have read about the film,’ opened Agee in a lengthy, three-part essay. ‘It is of interest, but chiefly as a definitive measure between the thing a man of genius puts before the world and the things the world is equipped to see in it.’ Others were not so kind or open-minded, with Howard Barnes in the Herald-Tribune calling the film ‘an affront to the intelligence’, while Bosley Crowther tore the film apart in the New York Times. Theatres screening Monsieur Verdoux were actively picketed by Catholic War Veterans and the American Legion, more in reaction to Chaplin personally than anything the film might have contained—it is unlikely that any of those picketing had taken the time to actually watch the movie.

It may be relentlessly old fashioned in style and approach, but Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux held up a perhaps unwelcome mirror to contemporary society. The core of the film’s meaning comes in the words of Verdoux uttered towards the end of the film. They are a briefer, more refined version of the passionate declaration that had climaxed The Great Dictator, and they are all the more effective for it: ‘As for being a mass killer, does the world not encourage it? Is it not building weapons of destruction for the sole purpose of mass killing? … As a mass killer, I am an amateur by comparison. … Wars, conflict—it’s all business. One murder makes a villain; millions, a hero. Number sanctify.’ The fact his victims were women could perhaps be read as Chaplin’s personal verdict following the Joan Barry case (as Henri Verdoux he admits: ‘I like women, but I don’t admire them’), even though he had begun formulating the film before that ‘landmark miscarriage of justice,’ as Los Angeles attorney Eugene L. Trope had described the case.

It may be relentlessly old fashioned in style and approach, but Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux held up a perhaps unwelcome mirror to contemporary society. The core of the film’s meaning comes in the words of Verdoux uttered towards the end of the film. They are a briefer, more refined version of the passionate declaration that had climaxed The Great Dictator, and they are all the more effective for it: ‘As for being a mass killer, does the world not encourage it? Is it not building weapons of destruction for the sole purpose of mass killing? … As a mass killer, I am an amateur by comparison. … Wars, conflict—it’s all business. One murder makes a villain; millions, a hero. Number sanctify.’ The fact his victims were women could perhaps be read as Chaplin’s personal verdict following the Joan Barry case (as Henri Verdoux he admits: ‘I like women, but I don’t admire them’), even though he had begun formulating the film before that ‘landmark miscarriage of justice,’ as Los Angeles attorney Eugene L. Trope had described the case.

Monsieur Verdoux was one of a series of dark, morbid, almost gothic, comedies released in the post-war years that included the likes of Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) and Britain’s Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949). Audiences took to those films well enough, and while Monsieur Verdoux flopped in America, it—true to Chaplin’s prediction—did well enough overseas to not be a financial catastrophe. The factor that made the film unpalatable to American audiences as the 1950s loomed was Chaplin himself, now seen as not quite ‘one of us’, a foreigner who had made his fortune in America but who seemingly ‘supported’ America’s enemy (the Cold War was just kicking off). As well as the political questions swirling around Chaplin, the Joan Barry case had relit all those moral concerns that had previously surrounded his marriages and divorces in the past , but which he had managed to more or less recover from. Now, Chaplin was being portrayed in the United States as morally and politically undesirable, and this would have huge consequences for both his movie-making and the remainder of his long life.

Trivia: The entire initial script of Monsieur Verdoux was rejected by the Breen office of censors due to ‘elements which seem to be anti-social in their concept and significance … the sections of the story in which Verdoux indicts “the system” and impugns the present-day social structure.’ There was about the proposed film ‘a distasteful flavour of illicit sex, which in our judgement is not good’. On a far more trivial (not to say ridiculous) note, the censors wanted there to be ‘no showing of, or suggestion of, toilets in the bathroom’ (a taboo that Alfred Hitchcock would finally shatter with Psycho, 1959). Chaplin met with Breen to discuss the screenplay, and changes were made but not as many or as extensive as the censors required—Chaplin followed the tried and tested method of altering some big items and simply ignoring the guidance offered on many much smaller concerns. The finished film was ultimately passed without further censorious comment.

Trivia: The entire initial script of Monsieur Verdoux was rejected by the Breen office of censors due to ‘elements which seem to be anti-social in their concept and significance … the sections of the story in which Verdoux indicts “the system” and impugns the present-day social structure.’ There was about the proposed film ‘a distasteful flavour of illicit sex, which in our judgement is not good’. On a far more trivial (not to say ridiculous) note, the censors wanted there to be ‘no showing of, or suggestion of, toilets in the bathroom’ (a taboo that Alfred Hitchcock would finally shatter with Psycho, 1959). Chaplin met with Breen to discuss the screenplay, and changes were made but not as many or as extensive as the censors required—Chaplin followed the tried and tested method of altering some big items and simply ignoring the guidance offered on many much smaller concerns. The finished film was ultimately passed without further censorious comment.

Charlie Says: ‘A day or so later [after talking with Orson Welles] it struck me that the idea of Landru would make a wonderful comedy. So I telephoned Welles. “Look, your proposed documentary about Landru has given me the idea for a comedy. It has nothing to do with Landru, but to clear everything, I am willing to pay you five thousand dollars, only because your proposition made me think of it.” … Thus a deal was negotiated. … I began writing Monsieur Verdoux.’—Charlie Chaplin, My Autobiography, 1964

‘I had been working three months on [Verdoux] when Joan Barry blew into Beverly Hills. The events that followed were not only sordid but sinister. Because I would not see her, she broke into the house, smashed windows, threatened my life and demanded money. … Barry blithely announced she was three months pregnant. … It was certainly no concern of mine. … A few hours later the newspapers were black with headlines. I was pilloried, excoriated, and vilified: Chaplin, the father of her unborn child, had had her arrested! … The following weeks were like a Kafka story. I found myself engrossed in the all-absorbing enterprise of fighting for my liberty [and] facing twenty years imprisonment!’—Charlie Chaplin, My Autobiography, 1964

Verdict: Overlong and frustratingly episodic, Monsieur Verdoux is nonetheless a triumph, largely thanks to Chaplin’s uncharacteristic yet nuanced performance, one so far removed from his regular character of the Tramp. If only he had played many more such characters than he did!

—Brian J. Robb

Next: Limelight (23 October 1952)

CHARLIE CHAPLIN: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION

An 80,000 word ebook chronicle of Chaplin’s early films from Keystone (1914) and Essanay (1915), based on the first year of blog postings at Chaplin: Film by Film with 20,000 words of supplemental biographical essays.

Amazon US | Amazon UK

Also available at Kobo, Nook, Apple, Scribd and other ebook outlets.

Released: 2 February 1914, Keystone

Released: 2 February 1914, Keystone

Although offered the services of a co-writer or even a ghostwriter, Chaplin insisted he must tell his own story in his own words. It was a process that soon got away from him. Rather than type his own work, Chaplin dictated his life story to his secretary, Eileen Burnier, relying on her to edit, clean up, and re-order his stream-of-consciousness anecdotes from all across his life and career. The book was promised for 1958, but it didn’t see publication, under the title My Autobiography, until 1964. Full of oversights and omissions, Chaplin’s autobiography was self aggrandising and indulgent. Lita Grey Chaplin—dismissed in a mere three lines despite being the mother of two of Chaplin’s surviving children—responded with a book of her own, Life With Chaplin, in an attempt to balance the scales. The spark behind the writing of Chaplin’s book, Sydney, died on 16 April 1965 aged 80—the same day was also Chaplin’s 76

Although offered the services of a co-writer or even a ghostwriter, Chaplin insisted he must tell his own story in his own words. It was a process that soon got away from him. Rather than type his own work, Chaplin dictated his life story to his secretary, Eileen Burnier, relying on her to edit, clean up, and re-order his stream-of-consciousness anecdotes from all across his life and career. The book was promised for 1958, but it didn’t see publication, under the title My Autobiography, until 1964. Full of oversights and omissions, Chaplin’s autobiography was self aggrandising and indulgent. Lita Grey Chaplin—dismissed in a mere three lines despite being the mother of two of Chaplin’s surviving children—responded with a book of her own, Life With Chaplin, in an attempt to balance the scales. The spark behind the writing of Chaplin’s book, Sydney, died on 16 April 1965 aged 80—the same day was also Chaplin’s 76

Chaplin’s instructional directing style was also difficult for Brando, who revered the ‘method’ style of acting, popular since the 1950s. Hedren recalled: ‘Charlie and Marlon put up with each other, you might say. Marlon was so insulted to see someone acting out his role and that’s why he wanted to leave. I thought it was charming and funny, but Marlon wanted to quit and Charlie had to convince him to stay on.’ Brando took to showing up late on set, dominating Loren, and attempted to ‘psych-out’ his elderly director. Chaplin was having none of it and very quickly restored his authority by threatening Brando with rival press conferences to air their grievances. ‘We’ll see who gets the biggest audience,’ he said, no doubt with a twinkle in his eye.

Chaplin’s instructional directing style was also difficult for Brando, who revered the ‘method’ style of acting, popular since the 1950s. Hedren recalled: ‘Charlie and Marlon put up with each other, you might say. Marlon was so insulted to see someone acting out his role and that’s why he wanted to leave. I thought it was charming and funny, but Marlon wanted to quit and Charlie had to convince him to stay on.’ Brando took to showing up late on set, dominating Loren, and attempted to ‘psych-out’ his elderly director. Chaplin was having none of it and very quickly restored his authority by threatening Brando with rival press conferences to air their grievances. ‘We’ll see who gets the biggest audience,’ he said, no doubt with a twinkle in his eye. Chaplin made a small cameo in the movie—his only appearance in one of his own films in colour. He played an elderly ship’s steward who, unaccountably given his profession, seemingly suffers from seasickness, recalling scenes from earlier ship-board Chaplin shorts. Chaplin’s steward had few lines, and as this was his final appearance in his final films, he left the world of moving pictures as he’d come in, silently.

Chaplin made a small cameo in the movie—his only appearance in one of his own films in colour. He played an elderly ship’s steward who, unaccountably given his profession, seemingly suffers from seasickness, recalling scenes from earlier ship-board Chaplin shorts. Chaplin’s steward had few lines, and as this was his final appearance in his final films, he left the world of moving pictures as he’d come in, silently. For the Sunday Express, the new Chaplin film was ‘old fashioned’ and ‘predictable’, while many critics complained about the miscast leads, deeming Loren and Brando unsuitable for such comedic farce material. Alexander Walker of the Evening Standard claimed Brando had been ‘directed to act in two styles, one reminiscent of a speak-your-weight machine and the other a sudden, manic frenzy peculiar to bedroom farce’. The Daily Mail was one of the few to lightly praise Chaplin’s late life effort: ‘Not by a long chalk the best of Chaplin, but all the same an agreeable escapist send-off for the New Year.’ In the United States, Time magazine called the film ‘probably the best movie made by a 77-year-old man. Unhappily, it is the worst movie made by Charlie Chaplin.’

For the Sunday Express, the new Chaplin film was ‘old fashioned’ and ‘predictable’, while many critics complained about the miscast leads, deeming Loren and Brando unsuitable for such comedic farce material. Alexander Walker of the Evening Standard claimed Brando had been ‘directed to act in two styles, one reminiscent of a speak-your-weight machine and the other a sudden, manic frenzy peculiar to bedroom farce’. The Daily Mail was one of the few to lightly praise Chaplin’s late life effort: ‘Not by a long chalk the best of Chaplin, but all the same an agreeable escapist send-off for the New Year.’ In the United States, Time magazine called the film ‘probably the best movie made by a 77-year-old man. Unhappily, it is the worst movie made by Charlie Chaplin.’ Charlie Chaplin died in his sleep on the morning of Christmas Day in 1977 at the age of 88 (Chaplin hated Christmas, and his daughter Geraldine even implied he may have deliberately chosen his moment of departure). A funeral two days later saw him buried at the local cemetery in Corzier-sur-Vevey, his home from the mid-1950s. There was a blackly comic postscript to Chaplin’s interment that he would no doubt have found humorously macabre—his body was stolen in March 1978 as part of a bungled ransom attempt. The police quickly caught the hopeless perpetrators, a pair of unemployed immigrants (Chaplin biographer David Robinson dubbed the pair ‘Keystone incompetents’). Chaplin’s coffin was recovered unharmed and re-interred, this time encased in reinforced concrete.

Charlie Chaplin died in his sleep on the morning of Christmas Day in 1977 at the age of 88 (Chaplin hated Christmas, and his daughter Geraldine even implied he may have deliberately chosen his moment of departure). A funeral two days later saw him buried at the local cemetery in Corzier-sur-Vevey, his home from the mid-1950s. There was a blackly comic postscript to Chaplin’s interment that he would no doubt have found humorously macabre—his body was stolen in March 1978 as part of a bungled ransom attempt. The police quickly caught the hopeless perpetrators, a pair of unemployed immigrants (Chaplin biographer David Robinson dubbed the pair ‘Keystone incompetents’). Chaplin’s coffin was recovered unharmed and re-interred, this time encased in reinforced concrete. Verdict: An unfortunately misfiring final effort from Chaplin. The film takes the better part of an hour to get going, Brando is miscast, and the farce is neither fast enough nor farcical enough. There’s good value to be had from Sydney Chaplin, Patrick Cargill, and (briefly, in the available cut) Margaret Rutherford. Chaplin’s twinkly cameo is another brief highlight, but A Countess From Hong Kong simply proves Chaplin should have stopped after A King in New York.—

Verdict: An unfortunately misfiring final effort from Chaplin. The film takes the better part of an hour to get going, Brando is miscast, and the farce is neither fast enough nor farcical enough. There’s good value to be had from Sydney Chaplin, Patrick Cargill, and (briefly, in the available cut) Margaret Rutherford. Chaplin’s twinkly cameo is another brief highlight, but A Countess From Hong Kong simply proves Chaplin should have stopped after A King in New York.— Project Postscript:

Project Postscript:

The writer-director had decided not to return to London permanently as he felt the extradition arrangements with the United States meant he could not be sure of his own long-term safety. He turned in his void re-entry permit at the US consulate and issued a statement: ‘It is not easy to uproot myself and my family from a country where I have lived for 40 years without a feeling of sadness, but since the end of the last war I have been the object of vicious propaganda by powerful reactionary groups who by their influence and by the aid of America’s yellow press have created an unhealthy atmosphere in which liberal-minded individuals can be singled out and persecuted. I have therefore given up my residence in the United States.’ This ‘persecution’ of ‘liberal-minded individuals’ and America’s ‘unhealthy atmosphere’ would be the backdrop for A King in New York.

The writer-director had decided not to return to London permanently as he felt the extradition arrangements with the United States meant he could not be sure of his own long-term safety. He turned in his void re-entry permit at the US consulate and issued a statement: ‘It is not easy to uproot myself and my family from a country where I have lived for 40 years without a feeling of sadness, but since the end of the last war I have been the object of vicious propaganda by powerful reactionary groups who by their influence and by the aid of America’s yellow press have created an unhealthy atmosphere in which liberal-minded individuals can be singled out and persecuted. I have therefore given up my residence in the United States.’ This ‘persecution’ of ‘liberal-minded individuals’ and America’s ‘unhealthy atmosphere’ would be the backdrop for A King in New York.

Chaplin’s deposed monarch, King Shahdov (his name suggests a ‘shadow’ personality; curiously it is depicted as ‘Shadov’ on the film credits) of Estrovia, has been overthrown by a cabal within his government following his plans to use atomic power to improve the lot of his people. Having fallen on hard times (the money looted from his kingdom has in turn been looted by his prime minister), the King becomes a celebrity and takes on advertising contracts in order to pay off his expensive hotel bills. He encounters modern culture, such as movies, and decides it’s not to his taste. A relationship with Dawn Addam’s advertising advisor continues Chaplin’s infatuation (on- and off-screen) with women far younger than he was—Chaplin was in his mid-60s, Addams in her mid-20s.

Chaplin’s deposed monarch, King Shahdov (his name suggests a ‘shadow’ personality; curiously it is depicted as ‘Shadov’ on the film credits) of Estrovia, has been overthrown by a cabal within his government following his plans to use atomic power to improve the lot of his people. Having fallen on hard times (the money looted from his kingdom has in turn been looted by his prime minister), the King becomes a celebrity and takes on advertising contracts in order to pay off his expensive hotel bills. He encounters modern culture, such as movies, and decides it’s not to his taste. A relationship with Dawn Addam’s advertising advisor continues Chaplin’s infatuation (on- and off-screen) with women far younger than he was—Chaplin was in his mid-60s, Addams in her mid-20s. As with

As with  Many of those caught up in accusations of Communism relocated to Europe with several prominent American filmmakers working in 1950s London on both film and television projects. Chaplin’s leading lady this time was Dawn Addams, who first made her mark in 1952’s MGM musical Singin’ in the Rain and had married a Prince in 1954 (she had previously auditioned for Chaplin’s

Many of those caught up in accusations of Communism relocated to Europe with several prominent American filmmakers working in 1950s London on both film and television projects. Chaplin’s leading lady this time was Dawn Addams, who first made her mark in 1952’s MGM musical Singin’ in the Rain and had married a Prince in 1954 (she had previously auditioned for Chaplin’s  The film was completed relatively quickly across a tight nine-week period, with an additional week devoted to location filming. Chaplin himself was under a strict limitation as to how long he could stay in Britain, largely for tax reasons and because he was in fear of attracting the attention of the American authorities who might decide at any moment to have him arrested. It is little wonder, then, if he was somewhat paranoid and irritated when filming A King in New York. As soon as the filming wrapped in summer 1956, Chaplin left for the relative quiet and solitude of Switzerland once more.

The film was completed relatively quickly across a tight nine-week period, with an additional week devoted to location filming. Chaplin himself was under a strict limitation as to how long he could stay in Britain, largely for tax reasons and because he was in fear of attracting the attention of the American authorities who might decide at any moment to have him arrested. It is little wonder, then, if he was somewhat paranoid and irritated when filming A King in New York. As soon as the filming wrapped in summer 1956, Chaplin left for the relative quiet and solitude of Switzerland once more. American audiences and critics would not officially see A King in New York for 16 years after its release, although some critics did sneak in a viewing, with the New Yorker dubbing it ‘maybe the worst film ever made by a celebrated film artist.’ British critics were more welcoming if not universally positive. ‘Never boring,’ was the conclusion of Kenneth Tynan writing in The Observer. ‘The points that are made—about the withdrawal of passports and the abject necessity of informing—are new to the screen, and it is about time somebody made them.’ For the Daily Mail, Chaplin’s latest was ‘a lumpish mixture of subtle slapstick and clumsy political satire’. In The Sunday Times, Dilys Powell described Chaplin’s character in A King in New York as the final step of his discarding of the Tramp guise, now he was simply playing himself onscreen. Some critics missed the ‘old-fashioned’ slapstick Chaplin and decried his ‘message-crammed’ later movies like

American audiences and critics would not officially see A King in New York for 16 years after its release, although some critics did sneak in a viewing, with the New Yorker dubbing it ‘maybe the worst film ever made by a celebrated film artist.’ British critics were more welcoming if not universally positive. ‘Never boring,’ was the conclusion of Kenneth Tynan writing in The Observer. ‘The points that are made—about the withdrawal of passports and the abject necessity of informing—are new to the screen, and it is about time somebody made them.’ For the Daily Mail, Chaplin’s latest was ‘a lumpish mixture of subtle slapstick and clumsy political satire’. In The Sunday Times, Dilys Powell described Chaplin’s character in A King in New York as the final step of his discarding of the Tramp guise, now he was simply playing himself onscreen. Some critics missed the ‘old-fashioned’ slapstick Chaplin and decried his ‘message-crammed’ later movies like  Chaplin—unusually for the 1950s—was aware of the economic value of his back catalogue. Many other film comedians, especially of the early silent years, did not control their own material, and Chaplin in fact did not have any say over future use of his Keystone and Essanay films, either. Everything else post-1918, though, had been produced at studios under licence or via his own studio. In 1954, Chaplin called his long-term camera operator/cinematographer Rollie Totheroh to clear out the vaults of his old studio and ship all the film material stored there to Switzerland. He had special adjustable temperature controlled storage vaults built in the basement of his Swiss home to store the material.

Chaplin—unusually for the 1950s—was aware of the economic value of his back catalogue. Many other film comedians, especially of the early silent years, did not control their own material, and Chaplin in fact did not have any say over future use of his Keystone and Essanay films, either. Everything else post-1918, though, had been produced at studios under licence or via his own studio. In 1954, Chaplin called his long-term camera operator/cinematographer Rollie Totheroh to clear out the vaults of his old studio and ship all the film material stored there to Switzerland. He had special adjustable temperature controlled storage vaults built in the basement of his Swiss home to store the material. Trivia:

Trivia:

That train of thought fed into his next movie, the final film he would make in the Unite States. By 1948 he was working on a project entitled ‘Footlights’—although he always intended it to be a film, he’d begun building the narrative in the form of a novella. He dictated his story, breaking occasionally to work on developing tunes with his piano that, as Peter Ackroyd puts it ‘might help to evoke the spirit of London immediately before the First World War’, filtered through the earlier London of his childhood. Although autobiographical in nature, the story as it unfolded was not about Chaplin himself, but a Chaplinesque figure that he would undoubtedly play. Towards the end of 1950, the novella had turned into a screenplay now called Limelight.

That train of thought fed into his next movie, the final film he would make in the Unite States. By 1948 he was working on a project entitled ‘Footlights’—although he always intended it to be a film, he’d begun building the narrative in the form of a novella. He dictated his story, breaking occasionally to work on developing tunes with his piano that, as Peter Ackroyd puts it ‘might help to evoke the spirit of London immediately before the First World War’, filtered through the earlier London of his childhood. Although autobiographical in nature, the story as it unfolded was not about Chaplin himself, but a Chaplinesque figure that he would undoubtedly play. Towards the end of 1950, the novella had turned into a screenplay now called Limelight. Rehearsals for Limelight began in September 1951. Chaplin’s production methods had changed considerably since the early days of 1914 when he and a gang of clowns could simply turn up to a Los Angeles park, camera equipment in hand, and make up a slapstick entertainment on the spot. The rehearsal period was partly mandated by the need for Bloom to train to master her role as a ballerina (she would be doubled in some bed scenes by Oona O’Neill). Filming actually began in November, and while as involved in every detail as before, Chaplin followed his recent, more efficient production process on Limelight.

Rehearsals for Limelight began in September 1951. Chaplin’s production methods had changed considerably since the early days of 1914 when he and a gang of clowns could simply turn up to a Los Angeles park, camera equipment in hand, and make up a slapstick entertainment on the spot. The rehearsal period was partly mandated by the need for Bloom to train to master her role as a ballerina (she would be doubled in some bed scenes by Oona O’Neill). Filming actually began in November, and while as involved in every detail as before, Chaplin followed his recent, more efficient production process on Limelight. While much of Limelight—a film that is overlong by at least half-an-hour—is maudlin and self-regarding, it is well-remembered for the only screen pairing of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. In his early days Chaplin had worked with such figures as Mabel Normand and Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle, whom he later came to eclipse in terms of productivity and popularity. Chaplin was a contemporary of both Keaton and Harold Lloyd (and Lloyd had a serious claim to having been the most popular of the three comics with audiences). For the final musical number of Limelight, Chaplin brought in Keaton as his stage partner partly due to the fact that his comic rival had fallen on hard times following a divorce and loss of his fortune.

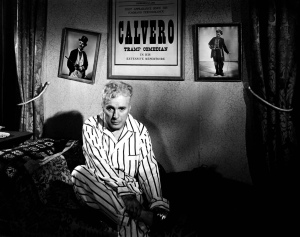

While much of Limelight—a film that is overlong by at least half-an-hour—is maudlin and self-regarding, it is well-remembered for the only screen pairing of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. In his early days Chaplin had worked with such figures as Mabel Normand and Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle, whom he later came to eclipse in terms of productivity and popularity. Chaplin was a contemporary of both Keaton and Harold Lloyd (and Lloyd had a serious claim to having been the most popular of the three comics with audiences). For the final musical number of Limelight, Chaplin brought in Keaton as his stage partner partly due to the fact that his comic rival had fallen on hard times following a divorce and loss of his fortune. When Limelight was released in October 1952, Chaplin summed up the critical reaction as ‘lukewarm’, which is at least better than outright hostility. Many critics noted how much this once silent comedian, who had so actively resisted the sound film for so long, now rather liked the sound of his own voice. This reaction was best summed up by Walter Kerr: ‘From the first reel of Limelight, it is perfectly clear that Chaplin now wants to talk, that he loves to talk, that in this film he intends to do little but talk!’ For others, though, Chaplin’s best moments in Limelight came with Calvero’s contemplative silences, where according to critic Robert Warshow Chaplin’s ‘true profundity’ lay.

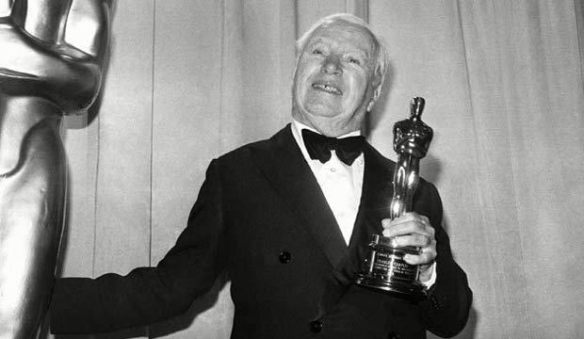

When Limelight was released in October 1952, Chaplin summed up the critical reaction as ‘lukewarm’, which is at least better than outright hostility. Many critics noted how much this once silent comedian, who had so actively resisted the sound film for so long, now rather liked the sound of his own voice. This reaction was best summed up by Walter Kerr: ‘From the first reel of Limelight, it is perfectly clear that Chaplin now wants to talk, that he loves to talk, that in this film he intends to do little but talk!’ For others, though, Chaplin’s best moments in Limelight came with Calvero’s contemplative silences, where according to critic Robert Warshow Chaplin’s ‘true profundity’ lay. Limelight, however, did not get a wide release across the United States. It was not seen much beyond the East Coast and New York area in 1952, with many cinema chains simply refusing to show the picture in reaction to Chaplin’s unfavourable public profile following the Joan Barry scandal and the fuss over his personal politics. Several Los Angeles theatres dropped planned screenings of the film when threatened by anti-Chaplin pickets on behalf of the American Legion (the organisation attempted to have release of the film entirely banned across the US). This situation, bizarrely, allowed Chaplin to win his first competitive Oscar, even if somewhat belatedly. The film was re-released in 1972, by which time it had picked up a more positive critical reputation, and as this release saw its first screenings in Los Angeles Limelight was eligible for contention in that year’s Academy Awards. As a result, Chaplin (along with collaborators Ray Rasch and Larry Russell) won the Oscar for Best Music, Original Dramatic Score for Limelight.

Limelight, however, did not get a wide release across the United States. It was not seen much beyond the East Coast and New York area in 1952, with many cinema chains simply refusing to show the picture in reaction to Chaplin’s unfavourable public profile following the Joan Barry scandal and the fuss over his personal politics. Several Los Angeles theatres dropped planned screenings of the film when threatened by anti-Chaplin pickets on behalf of the American Legion (the organisation attempted to have release of the film entirely banned across the US). This situation, bizarrely, allowed Chaplin to win his first competitive Oscar, even if somewhat belatedly. The film was re-released in 1972, by which time it had picked up a more positive critical reputation, and as this release saw its first screenings in Los Angeles Limelight was eligible for contention in that year’s Academy Awards. As a result, Chaplin (along with collaborators Ray Rasch and Larry Russell) won the Oscar for Best Music, Original Dramatic Score for Limelight. United Artists had been largely profitable since the late-1930s, although the business had declined in recent years. Chaplin’s involvement in the company had been minimal. Various management teams had come and gone, as had various ‘output’ deals with independent studios that would see UA distribute their films. By the start of the 1950s, only Mary Pickford and Chaplin remained of the original founders. They had allowed producers Arthur B. Krim and Robert Benjamin to run UA for a period of 10 years, with a view to them becoming co-owners if they were successful. The pair quickly released two successful films, The African Queen (1951) and Moulin Rouge (1952), both directed by John Huston. By 1955, following his departure from the US (see below), Chaplin had sold his 25 per cent of the company directly to Krim and Benjamin for just over $1 million. That left Pickford, who followed suit just a year later, selling up for $3 million. For the first time, United Artists was free to pursue a new destiny without any of its illustrious founders. Krim and Benjamin would take the company public in 1957, and decades of success (backing the James Bond franchise) and trouble (several near bankruptcies and takeovers, including by MGM and Turner) followed.

United Artists had been largely profitable since the late-1930s, although the business had declined in recent years. Chaplin’s involvement in the company had been minimal. Various management teams had come and gone, as had various ‘output’ deals with independent studios that would see UA distribute their films. By the start of the 1950s, only Mary Pickford and Chaplin remained of the original founders. They had allowed producers Arthur B. Krim and Robert Benjamin to run UA for a period of 10 years, with a view to them becoming co-owners if they were successful. The pair quickly released two successful films, The African Queen (1951) and Moulin Rouge (1952), both directed by John Huston. By 1955, following his departure from the US (see below), Chaplin had sold his 25 per cent of the company directly to Krim and Benjamin for just over $1 million. That left Pickford, who followed suit just a year later, selling up for $3 million. For the first time, United Artists was free to pursue a new destiny without any of its illustrious founders. Krim and Benjamin would take the company public in 1957, and decades of success (backing the James Bond franchise) and trouble (several near bankruptcies and takeovers, including by MGM and Turner) followed. The comedians initial reaction was to declare his unequivocal intention to return once he had launched Limelight in London. He would, he said, be more than happy to face any allegations or accusations that could be made against him—after all, he’d taken on both Joan Barry and HUAC and triumphed. At the back of Chaplin’s mind, however, was the potential loss of all his financial assets (his studio, bank accounts, and various remaining investments) if they were to be seized by the government—this would mean for him a return to the childhood poverty he had been running from all his life. He’d been lucky to avoid the financial crash of 1929, so he wasn’t prepared to lose everything to the American government without a fight.

The comedians initial reaction was to declare his unequivocal intention to return once he had launched Limelight in London. He would, he said, be more than happy to face any allegations or accusations that could be made against him—after all, he’d taken on both Joan Barry and HUAC and triumphed. At the back of Chaplin’s mind, however, was the potential loss of all his financial assets (his studio, bank accounts, and various remaining investments) if they were to be seized by the government—this would mean for him a return to the childhood poverty he had been running from all his life. He’d been lucky to avoid the financial crash of 1929, so he wasn’t prepared to lose everything to the American government without a fight. In November, Chaplin had Oona return to Hollywood via New York, where she spent several days retrieving Chaplin’s financial papers and redirecting his assets, including shifting over $4 million to European banks. She closed up Chapin’s home on Summit Drive, where he had lived the longest, and arranged for the furniture to be shipped to Europe. In her absence, Chaplin was said to be suffering a form of nervous exhaustion, fearing she might die in a plane crash or somehow be detained by FBI agents. It was no fanciful fear, as Oona found that FBI agents had been questioning the staff who remained at Summit Drive, clearly preparing a ‘morals’ case against Chaplin. Many in his circle of friends, work colleagues, and acquaintances were questioned, but little of any value was ultimately uncovered. However, once Oona was back safely in London, it was clear to Chaplin that his days as a non-citizen of the United States had firmly come to an end.

In November, Chaplin had Oona return to Hollywood via New York, where she spent several days retrieving Chaplin’s financial papers and redirecting his assets, including shifting over $4 million to European banks. She closed up Chapin’s home on Summit Drive, where he had lived the longest, and arranged for the furniture to be shipped to Europe. In her absence, Chaplin was said to be suffering a form of nervous exhaustion, fearing she might die in a plane crash or somehow be detained by FBI agents. It was no fanciful fear, as Oona found that FBI agents had been questioning the staff who remained at Summit Drive, clearly preparing a ‘morals’ case against Chaplin. Many in his circle of friends, work colleagues, and acquaintances were questioned, but little of any value was ultimately uncovered. However, once Oona was back safely in London, it was clear to Chaplin that his days as a non-citizen of the United States had firmly come to an end.

Landru was notoriously known as ‘Bluebeard’. Between the end of 1915, just as Chaplin was enjoying his first fame, and early 1919 (between the release of Chaplin’s

Landru was notoriously known as ‘Bluebeard’. Between the end of 1915, just as Chaplin was enjoying his first fame, and early 1919 (between the release of Chaplin’s  To play a role very far removed from his internationally recognised Tramp, Chaplin decide it was necessary to dramatically change his entire appearance . He spent six weeks growing a genuine moustache, wax-tipped in the approved French manner. He allowed the grey that featured in his natural hair to show through for the first time on screen, and he dressed in exquisite suits, complete with a range of hats and canes. As Henri Verdoux, Chaplin was, to all intents-and-purposes, the most polite and dapper ‘lady killer’ in town.

To play a role very far removed from his internationally recognised Tramp, Chaplin decide it was necessary to dramatically change his entire appearance . He spent six weeks growing a genuine moustache, wax-tipped in the approved French manner. He allowed the grey that featured in his natural hair to show through for the first time on screen, and he dressed in exquisite suits, complete with a range of hats and canes. As Henri Verdoux, Chaplin was, to all intents-and-purposes, the most polite and dapper ‘lady killer’ in town. Chaplin as Verdoux adopts a variety of aliases to access his various ‘wives’. At home waits his real wife, Mona (Mady Correll), looking after their young son, Peter. Also waiting is Lydia Florey (Margaret Hoffman), who believes Verdoux to be an engineer who has been travelling for three months. She’s the first victim we see Verdoux eliminate, only to make use of her funds the next morning. In his sights as his next victim is Marie Grosnay (Isobel Elsom) who comes to view his for-sale house. Also in play is the alarming Annabella (Martha Raye), who believes Verdoux to be a sailor, Captain Bonheur. She proves somewhat indestructible, surviving all of Verdoux’s attempts to remove her, whether through poisoned wine or the more direct approach of tossing her overboard from his boat. It is Annabella who ultimately thwarts his attempt to marry Grosnay. Also featured is ‘The Girl’, a young woman Verdoux finds on the street—a ‘derelict’, and in no way a prostitute, thanks to film censor intervention. He plans to try out his poison on her, but her commitment to looking after her now deceased injured war veteran husband stays Verdoux’s hand. She ultimately makes good in life as the wife, or perhaps companion, to an arms dealer making a fortune from war. That’s the core of Chaplin’s take on Verdoux—his individual acts are immoral, but society’s collective acts of war and destruction are seen as patriotic. It was a view that would bring Chaplin further trouble later.

Chaplin as Verdoux adopts a variety of aliases to access his various ‘wives’. At home waits his real wife, Mona (Mady Correll), looking after their young son, Peter. Also waiting is Lydia Florey (Margaret Hoffman), who believes Verdoux to be an engineer who has been travelling for three months. She’s the first victim we see Verdoux eliminate, only to make use of her funds the next morning. In his sights as his next victim is Marie Grosnay (Isobel Elsom) who comes to view his for-sale house. Also in play is the alarming Annabella (Martha Raye), who believes Verdoux to be a sailor, Captain Bonheur. She proves somewhat indestructible, surviving all of Verdoux’s attempts to remove her, whether through poisoned wine or the more direct approach of tossing her overboard from his boat. It is Annabella who ultimately thwarts his attempt to marry Grosnay. Also featured is ‘The Girl’, a young woman Verdoux finds on the street—a ‘derelict’, and in no way a prostitute, thanks to film censor intervention. He plans to try out his poison on her, but her commitment to looking after her now deceased injured war veteran husband stays Verdoux’s hand. She ultimately makes good in life as the wife, or perhaps companion, to an arms dealer making a fortune from war. That’s the core of Chaplin’s take on Verdoux—his individual acts are immoral, but society’s collective acts of war and destruction are seen as patriotic. It was a view that would bring Chaplin further trouble later. That was thought to be the end of the matter, and while things went quiet for a while, Joan Barry never really went away. By the end of 1942, she was back to trouble Chaplin once more. A couple of days before Christmas, Barry broke into Chaplin’s house, wielding a gun and threatening suicide. Apparently, with Chaplin’s willing acquiescence, she then stayed the night. She was back a week later, like a stalker, and this time Chaplin took her to the police. That apparent warning shot wasn’t enough to make her change her behaviour and she was found the following night on Chaplin’s grounds, once again armed.

That was thought to be the end of the matter, and while things went quiet for a while, Joan Barry never really went away. By the end of 1942, she was back to trouble Chaplin once more. A couple of days before Christmas, Barry broke into Chaplin’s house, wielding a gun and threatening suicide. Apparently, with Chaplin’s willing acquiescence, she then stayed the night. She was back a week later, like a stalker, and this time Chaplin took her to the police. That apparent warning shot wasn’t enough to make her change her behaviour and she was found the following night on Chaplin’s grounds, once again armed. The use of the Mann Act in this way by prosecutors was targetted against those (like Chaplin) who’d spoken out in favour of a ‘second front’ during the war to help relieve pressure on Russia; a similar prosecution had been considered against writer Theodore Dreiser for similar reasons, but was not ultimately progressed. Now, Chaplin was the target. One newspaper commentator even went so far as to claim that Chaplin might have been the victim of a ‘fascist clique in America’ in retaliation for his caricature of Hitler in The Great Dictator. The Washington Times-Herald opined that ‘this is persecution of Chaplin by the Federal government’.

The use of the Mann Act in this way by prosecutors was targetted against those (like Chaplin) who’d spoken out in favour of a ‘second front’ during the war to help relieve pressure on Russia; a similar prosecution had been considered against writer Theodore Dreiser for similar reasons, but was not ultimately progressed. Now, Chaplin was the target. One newspaper commentator even went so far as to claim that Chaplin might have been the victim of a ‘fascist clique in America’ in retaliation for his caricature of Hitler in The Great Dictator. The Washington Times-Herald opined that ‘this is persecution of Chaplin by the Federal government’. On some posters for Monsieur Verdoux, a challenge was thrown out to audiences that had grown-up with the ‘old’ Charlie Chaplin, the knockabout Keystone Tramp: ‘Chaplin Changes!’ the poster declared, and then asked, pointedly, ‘Can You?’ Chaplin knew the film would be challenging to some audiences, and he expected critics to dislike it. At a press conference to launch the movie in New York in April 1947 he invited the attending reporters to ‘proceed with the butchery’. Many of the questions concerned what ‘message’ Chaplin was trying to communicate, and whether he felt audiences would be willing to follow him in this new, somewhat startling direction. Chaplin’s supposed ‘Communist sympathies’ were also queried, something he denied although he was happy to admit to having supported Russia as ‘a wartime ally’. The press conference rapidly became an inquisition with a free-for-all as journalists hurled questions to Chaplin about his nationality status, his income, and his refusal to fight for Britain in either of the World Wars. Getting back on topic, Chaplin was finally asked about his reaction to the reviews of his latest film: ‘Well, the one optimistic note is that they were mixed,’ said the screen clown.

On some posters for Monsieur Verdoux, a challenge was thrown out to audiences that had grown-up with the ‘old’ Charlie Chaplin, the knockabout Keystone Tramp: ‘Chaplin Changes!’ the poster declared, and then asked, pointedly, ‘Can You?’ Chaplin knew the film would be challenging to some audiences, and he expected critics to dislike it. At a press conference to launch the movie in New York in April 1947 he invited the attending reporters to ‘proceed with the butchery’. Many of the questions concerned what ‘message’ Chaplin was trying to communicate, and whether he felt audiences would be willing to follow him in this new, somewhat startling direction. Chaplin’s supposed ‘Communist sympathies’ were also queried, something he denied although he was happy to admit to having supported Russia as ‘a wartime ally’. The press conference rapidly became an inquisition with a free-for-all as journalists hurled questions to Chaplin about his nationality status, his income, and his refusal to fight for Britain in either of the World Wars. Getting back on topic, Chaplin was finally asked about his reaction to the reviews of his latest film: ‘Well, the one optimistic note is that they were mixed,’ said the screen clown. It may be relentlessly old fashioned in style and approach, but Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux held up a perhaps unwelcome mirror to contemporary society. The core of the film’s meaning comes in the words of Verdoux uttered towards the end of the film. They are a briefer, more refined version of the passionate declaration that had climaxed The Great Dictator, and they are all the more effective for it: ‘As for being a mass killer, does the world not encourage it? Is it not building weapons of destruction for the sole purpose of mass killing? … As a mass killer, I am an amateur by comparison. … Wars, conflict—it’s all business. One murder makes a villain; millions, a hero. Number sanctify.’ The fact his victims were women could perhaps be read as Chaplin’s personal verdict following the Joan Barry case (as Henri Verdoux he admits: ‘I like women, but I don’t admire them’), even though he had begun formulating the film before that ‘landmark miscarriage of justice,’ as Los Angeles attorney Eugene L. Trope had described the case.

It may be relentlessly old fashioned in style and approach, but Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux held up a perhaps unwelcome mirror to contemporary society. The core of the film’s meaning comes in the words of Verdoux uttered towards the end of the film. They are a briefer, more refined version of the passionate declaration that had climaxed The Great Dictator, and they are all the more effective for it: ‘As for being a mass killer, does the world not encourage it? Is it not building weapons of destruction for the sole purpose of mass killing? … As a mass killer, I am an amateur by comparison. … Wars, conflict—it’s all business. One murder makes a villain; millions, a hero. Number sanctify.’ The fact his victims were women could perhaps be read as Chaplin’s personal verdict following the Joan Barry case (as Henri Verdoux he admits: ‘I like women, but I don’t admire them’), even though he had begun formulating the film before that ‘landmark miscarriage of justice,’ as Los Angeles attorney Eugene L. Trope had described the case. Trivia:

Trivia:

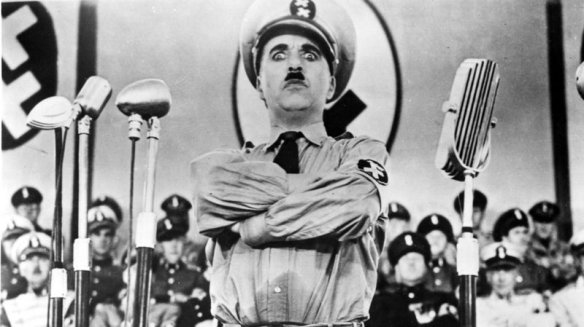

The odd similarity between the appearances of Chaplin and of Hitler was hard to ignore in the later 1930s. It had inspired a comic song by British performer Tommy Handley entitled ‘Who is That Man Who Looks Like Charlie Chaplin?’ and was often used by newspaper cartoonist to make satirical political points. The similarity was not simply in their appearance—Chaplin and Hitler had been born in the same April week in 1889. This was something Chaplin could not ignore, especially when in the wake of Modern Times the German authorities at the direction of Hitler began to ban his films.

The odd similarity between the appearances of Chaplin and of Hitler was hard to ignore in the later 1930s. It had inspired a comic song by British performer Tommy Handley entitled ‘Who is That Man Who Looks Like Charlie Chaplin?’ and was often used by newspaper cartoonist to make satirical political points. The similarity was not simply in their appearance—Chaplin and Hitler had been born in the same April week in 1889. This was something Chaplin could not ignore, especially when in the wake of Modern Times the German authorities at the direction of Hitler began to ban his films. Direct inspiration came from a viewing of the Leni Rienfenstahl German propaganda film The Triumph of the Will (1935). Chaplin saw the film with fellow director Rene Clair, who found it horrifying while Chaplin thought it a hilarious production, so ridiculously over-the-top was the propaganda element. Watching Hitler giving speeches, Chaplin began to see how he could imitate and so satirise Hitler’s mannerisms and movements, even his vocal inflections. He followed a viewing of the Rienfenstahl film with careful study of newsreels of Hitler’s speeches, and slowly developed his caricature of the dictator’s oratory. The core of The Great Dictator lay in this simple conceit.

Direct inspiration came from a viewing of the Leni Rienfenstahl German propaganda film The Triumph of the Will (1935). Chaplin saw the film with fellow director Rene Clair, who found it horrifying while Chaplin thought it a hilarious production, so ridiculously over-the-top was the propaganda element. Watching Hitler giving speeches, Chaplin began to see how he could imitate and so satirise Hitler’s mannerisms and movements, even his vocal inflections. He followed a viewing of the Rienfenstahl film with careful study of newsreels of Hitler’s speeches, and slowly developed his caricature of the dictator’s oratory. The core of The Great Dictator lay in this simple conceit. Shooting actually started just days after the war began and ran through until March 1940, a rather rapid production process in comparison to some of Chaplin’s past endeavours (but not as rapid as Hitler’s assault on the countries of Europe). His first drafts of the script are, at their core, remarkably similar to what was to finally end up onscreen, including a shorter version of the climatic speech. For the first time Chaplin deviated from his use of the regular supporting cast members he’d worked with over many years in favour of hiring several well-established acting names. Henry Daniell, with a reputation for playing villains, took on the Goebbels-like role of Garbitsch and played it rather straight in stark contrast to the comic acting going on around him, particularly from Chaplin as Adenoid Hynkel and Jack Oakie as the Mussolini-equivalent, Benzino Napaloni, dictator of Bacteria. Billy Gilbert, familiar from his work with Laurel and Hardy especially in 1932’s Oscar-winning The Music Box, partnered Daniell by playing the Goering inspired character of Herring.

Shooting actually started just days after the war began and ran through until March 1940, a rather rapid production process in comparison to some of Chaplin’s past endeavours (but not as rapid as Hitler’s assault on the countries of Europe). His first drafts of the script are, at their core, remarkably similar to what was to finally end up onscreen, including a shorter version of the climatic speech. For the first time Chaplin deviated from his use of the regular supporting cast members he’d worked with over many years in favour of hiring several well-established acting names. Henry Daniell, with a reputation for playing villains, took on the Goebbels-like role of Garbitsch and played it rather straight in stark contrast to the comic acting going on around him, particularly from Chaplin as Adenoid Hynkel and Jack Oakie as the Mussolini-equivalent, Benzino Napaloni, dictator of Bacteria. Billy Gilbert, familiar from his work with Laurel and Hardy especially in 1932’s Oscar-winning The Music Box, partnered Daniell by playing the Goering inspired character of Herring. Chaplin cast Goddard as Hannah (presumably deliberated named for his mother), the waif-like companion to the little barber, a role not a million miles away from that she had on

Chaplin cast Goddard as Hannah (presumably deliberated named for his mother), the waif-like companion to the little barber, a role not a million miles away from that she had on  Chaplin’s detailed attempts to guide his wife’s performance didn’t help matters. Dan James noted: ‘There was some anger on both sides, but he worked very hard with her. Sometimes he would make 25 or 30 takes. He would stand in her place on the set and try and give her the tone and the gestures. It was a method he had been able to use in silent films; it could not work so well on a talking picture.’ Part of the problem for Chaplin was that filmmaking had changed, as had screen acting, but his infrequent filmmaking endeavours had not allowed him to keep up with the trends or further develop his art. Essentially, he wasn’t keeping up with the times, and was at least a decade behind everyone else in sound filmmaking techniques. Just as the events between the wars had bypassed the Jewish barber, so developments in modern 1930s filmmaking had bypassed Chaplin who worked as though it were still 1918.