Release Date: 30 January 1931

Written & Directed by Charlie Chaplin

Duration: 87 minutes

With: Virginia Cherrill, Florence Lee, Harry Meyers, Allan Garcia, Joe Van Meter, Albert Austin, Hank Mann, Eddie Baker

Story: The Tramp falls in love with a blind flower girl while also pursuing a complicated friendship with a rich alcoholic friend who never remembers him when sober…

Production: Even before the public had even seen The Circus, and certainly long before Charlie Chaplin received his special Oscar for the film, the writer-director-performer had moved on to his next project, his fourth full-length feature film and his 75th film overall since 1914. This was highly unusual for Chaplin, who liked to take his own good time developing and reworking potential film material (financial pressures, from his recent divorce and tax troubles, may have been a motivator). Since he’d completed work on The Circus, he now also had to contend with significant changes in the film business—the long mooted possibility of sound cinema had come to pass. His brother, Sydney, had already appeared in a Warner Bros. Vitaphone sound short in 1926 entitled The Better ‘Ole, so the Chaplin brothers were only too aware of the implications of these major industry developments. How would the greatest silent comedian of them all react to this new direction? In typical Chaplin style, he virtually chose to ignore it altogether.

Production: Even before the public had even seen The Circus, and certainly long before Charlie Chaplin received his special Oscar for the film, the writer-director-performer had moved on to his next project, his fourth full-length feature film and his 75th film overall since 1914. This was highly unusual for Chaplin, who liked to take his own good time developing and reworking potential film material (financial pressures, from his recent divorce and tax troubles, may have been a motivator). Since he’d completed work on The Circus, he now also had to contend with significant changes in the film business—the long mooted possibility of sound cinema had come to pass. His brother, Sydney, had already appeared in a Warner Bros. Vitaphone sound short in 1926 entitled The Better ‘Ole, so the Chaplin brothers were only too aware of the implications of these major industry developments. How would the greatest silent comedian of them all react to this new direction? In typical Chaplin style, he virtually chose to ignore it altogether.

‘They are spoiling the oldest art in the world, the art of pantomime,’ complained Chaplin of the headlong drive of the industry to implement sound. From the debut of The Jazz Singer in 1927, nothing would ever be the same, even though that was not a ‘true’ sound film as it just featured elements of music and dialogue. The first full sound film was 1928’s Lights of New York, driving cinemas across the US (and then the world) to rapidly install sound equipment. ‘They are ruining the great beauty of silence,’ lamented Chaplin. ‘They are deafening the meaning of the screen.’ Chaplin feared the cinema sound revolution would be ‘fatal’ for his comic movies.

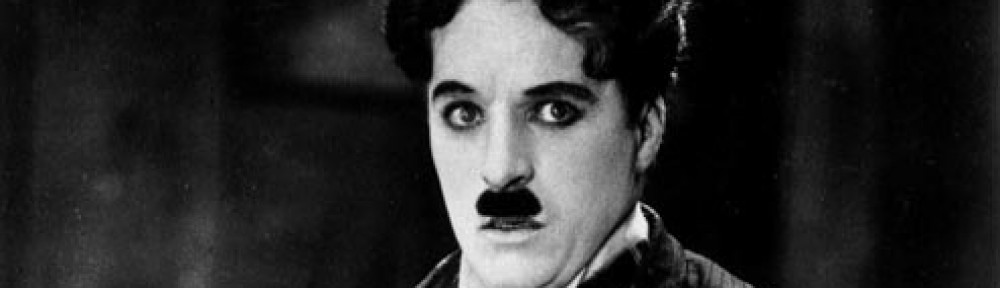

One of the greatest benefits of the silence of Chaplin’s Tramp was the character’s effortless appeal internationally. His was the language of mime, of pantomime, not words. His physicality and his face revealed his emotions. His actions spoke louder than any words could—and they were understood in any and all languages across the globe. The Tramp was an international ‘everyman’ representing humanity the world over. If he were to speak, would that not change forever his essential nature?

Chaplin had many things to think about. Would the arrival and dominance of sound cinema mean the end of silent movies? Would his past work suddenly become passée, old fashioned, out of tune with the times? Could he still make films in this brave new world he was so fearful of? If the Tramp were to speak, what would he sound like? Chaplin’s own speaking voice featured a soft, cultured, English accent—surely that’s not what his huge audience of American (and international) filmgoers thought the character they’d loved on screen for so many years would sound like. It was certainly a conundrum, one that threatened Chaplin’s very abilities as an entertainer.

Chaplin had many things to think about. Would the arrival and dominance of sound cinema mean the end of silent movies? Would his past work suddenly become passée, old fashioned, out of tune with the times? Could he still make films in this brave new world he was so fearful of? If the Tramp were to speak, what would he sound like? Chaplin’s own speaking voice featured a soft, cultured, English accent—surely that’s not what his huge audience of American (and international) filmgoers thought the character they’d loved on screen for so many years would sound like. It was certainly a conundrum, one that threatened Chaplin’s very abilities as an entertainer.

There was much speculation about Chaplin’s options. In September 1929 Film Weekly ran a story headlined ‘Will Chaplin Talk?’, asking the question that was on everyone’s mind. Chaplin’s lawyer Nathan Burkan said: ‘It is still undecided whether or not this film will be a talkie’, suggesting that Chaplin was keeping his options open. ‘Charlie’s attitude to “talkies” at the present time is that they are interesting, but that he does not consider that speech is in any way essential to screen art,’ said Burkan, further suggesting that Chaplin saw his silent ‘art’ as being something quite separate to the mainstream direction movies were taking. ‘The script of City Lights contains dialogue,’ confirmed Burkan, ‘and it is almost certain the film will contain some speech, but whether Charlie will break his silence is an open question…’

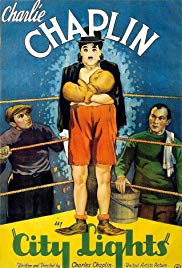

The ideas for what would become City Lights (‘A Comedy Romance in Pantomime’, according to a title card) had come to Chaplin during the production of The Circus, so he’d set about developing the film in the traditional way, giving little thought to the advent of sound. He had three characters—the Tramp, a blind flower seller, and a millionaire, whom he saves from a drunken suicide attempt. Around these he would build his drama. When the millionaire was in his cups, the Tramp would be his best pal, but when sober he would refuse to even recognise him (in an interview, Chaplin called the character a ‘Jekyll and Hyde inebriate’). Confusion as to who is who causes the blind girl to think of the kindly Tramp as her benefactor, when it is in fact the rich millionaire. It is his money that buys her the operation she needs to restore her sight, yet when she can see she doesn’t initially recognise the Tramp. The moment of dawning realisation that makes up the climax of City Lights is considered one of the greatest scenes in all cinema.

The ideas for what would become City Lights (‘A Comedy Romance in Pantomime’, according to a title card) had come to Chaplin during the production of The Circus, so he’d set about developing the film in the traditional way, giving little thought to the advent of sound. He had three characters—the Tramp, a blind flower seller, and a millionaire, whom he saves from a drunken suicide attempt. Around these he would build his drama. When the millionaire was in his cups, the Tramp would be his best pal, but when sober he would refuse to even recognise him (in an interview, Chaplin called the character a ‘Jekyll and Hyde inebriate’). Confusion as to who is who causes the blind girl to think of the kindly Tramp as her benefactor, when it is in fact the rich millionaire. It is his money that buys her the operation she needs to restore her sight, yet when she can see she doesn’t initially recognise the Tramp. The moment of dawning realisation that makes up the climax of City Lights is considered one of the greatest scenes in all cinema.

Chaplin discovered his newest leading lady in the audience of a boxing match he was attending (Chaplin gives a different, even less likely account of their first meeting in his autobiography). Virginia Cherrill was aged 20 (too old to attract Chaplin’s romantic interest, perhaps?) and not an actress, but she had the right, almost ethereal looks that Chaplin knew he needed for the blind flower seller. He had considered using Georgia Hale (from The Gold Rush), but his motivation here seems to have been more lustful than professional. Merna Kennedy (the star of The Circus) was listed in early Chaplin Studio production records for City Lights, but she is not known to have actively participated in the making of the film.

Lack of acting experience for Chaplin was always better, as it allowed him to mould her performance precisely to his needs without challenge. Cherrill, for her part, was apparently divorced and happy to swan about society living off her alimony payments. Invited to star in a movie, she simply looked upon it as another jolly wheeze to be pursued for as long as it amused her.

Cherrill’s first scene, in which she offers a flower up to the Tramp, became legendary not so much for its content but for the reputed 342 takes that Chaplin indulged in to get exactly what he wanted. Even though the film was silent, he insisted that she say her line ‘A flower, sir?’ just so. If her expression did not touch him, he would take the scene again. Sometimes it was her gesturing that was off, or the way she looked at him, or looked past him. Little details obsessed Chaplin, and this repeated striving to get Cherrill to do exactly what he wanted was the inevitable downside of his dependence on an actress he openly called ‘an amateur’.

Cherrill’s first scene, in which she offers a flower up to the Tramp, became legendary not so much for its content but for the reputed 342 takes that Chaplin indulged in to get exactly what he wanted. Even though the film was silent, he insisted that she say her line ‘A flower, sir?’ just so. If her expression did not touch him, he would take the scene again. Sometimes it was her gesturing that was off, or the way she looked at him, or looked past him. Little details obsessed Chaplin, and this repeated striving to get Cherrill to do exactly what he wanted was the inevitable downside of his dependence on an actress he openly called ‘an amateur’.

Cherrill was flighty, and in no way as committed to the making of the film as Chaplin inevitably was. One day she walked off the set, declaring she had to attend an appointment with her hairdresser. Chaplin flew into a rage, and then retreated to his bed for three days, unable to face the work, or—perhaps—his leading lady, who had disappointed him so. They did not get on personally, and more than once Chaplin fired his star, only to realise that he couldn’t face the prospect of starting all over again with someone new.

A witness to Chaplin’s tried and tested directing method, in which he acted out all the parts as a guide for his actors, was child actor Robert Parrish, who lated grew up to become a director himself. Writing in his memoir, he recalled: ‘[Chaplin] became a kind of dervish, playing all the parts, using all the props, seeing and cane-twirling as the Tramp, not seeing and grateful as the blind girl, pea-shooting as the newsboys. [We] watched as Charlie did his show. Finally, he had it all worked out and reluctantly gave us back our parts. I felt that he would much rather have played all of them himself.’ Virginia Cherrill too recalled Chaplin’s approach to directing her: ‘It seemed that the times you thought it was good, he’d hate it, and the other times when you felt flat and forced, he’d say it was great. If he enjoyed something, he’d do it forever until he was bored.’

A huge new city street set was constructed in the Chaplin studio for City Lights. It was built in a ‘T’ shape, thus allowing for deep street views, and populated with crowds of extras and plenty of vehicles to give the feel of a bustling city. A mix of the world’s greatest cities—New York, London, Paris—Chaplin’s fantasy conurbation included a theatre and a cabaret, an art store, and the monument seen at the film’s opening, as well as the flower store of the climax.

It has been suggested that rising star Jean Harlow was among the City Lights extras during a restaurant scene. If she was, it seems likely her scene was reshot without her as she is not readily visible in the film. According to Glenn Mitchell, Chaplin had cast Henry Clive as the millionaire but found him difficult to work with. The actor was fired and the part recast with Harry Meyers, meaning all the scenes featuring the millionaire had to be re-taken. It is likely that if she was originally in the film at all, Harlow may have appeared in one of the now replaced scenes with Henry Clive. Before City Lights was released in 1931, Jean Harlow would anyway go on to find fame on her own. It was to be short lived, as she died in 1937 aged just 26.

Also fired during production was Chaplin’s assistant Harry Crocker, who’d played the tightrope walker Rex in Chaplin’s preceding film, The Circus. Behind the scenes candid film footage released as part of the indispensable Unknown Chaplin (1983) documentary shows Chaplin becoming frustrated with Crocker on the set of City Lights. As a result of their differences on this production (which remain a mystery; Chaplin biographer David Robinson suggests it was something ‘extremely personal’), Crocker was let go. He and Chaplin later reconciled and Crocker again worked for the comic prior to Chaplin’s departure from the United States in 1952.

Also fired during production was Chaplin’s assistant Harry Crocker, who’d played the tightrope walker Rex in Chaplin’s preceding film, The Circus. Behind the scenes candid film footage released as part of the indispensable Unknown Chaplin (1983) documentary shows Chaplin becoming frustrated with Crocker on the set of City Lights. As a result of their differences on this production (which remain a mystery; Chaplin biographer David Robinson suggests it was something ‘extremely personal’), Crocker was let go. He and Chaplin later reconciled and Crocker again worked for the comic prior to Chaplin’s departure from the United States in 1952.

Chaplin lost the month of March 1929 to illness, but returned to the set at the beginning of April with renewed vigour and commitment to work positively with Cherrill and get his film finished. The break from filming had been useful, as a major operation had been undertaken to move the La Brea studio frontage (mainly offices) back 15 feet as mandated by the city’s desire to widen the road. The construction work was interfering with the making of City Lights, even though the film was defiantly silent. Production on the film was essentially halted through July and August, the summer of 1929, until the building work in the studio was done.

Chaplin wrapped filming in the autumn of 1930 (after many stop-start delays), and then decided that his only concession to the demands of sound cinema would be an original score of his own composition. It was a new delay to the completion of the picture, and a new, artistic and creative distraction for Chaplin himself. It was also the start of a slippery slope, because having decided to add music, he then considered working in some spot sound effects and even little bits of gibberish dialogue for crowd scenes. In fact, his use of a kazoo sound for the speech of the dignitaries was both a dig at such pompous people but also at talking films themselves. He made clever use of a whistle sound, having the Tramp swallow one and so almost ‘talk’ through it. These were all compromises with the way the art of cinema was going, and each of them no doubt struck at Chaplin’s heart, but he was fearful that if he did nothing and simply presented City Lights as a ‘true’ silent picture that audiences, now used to the new world of sound, would simply reject it outright.

Chaplin wrapped filming in the autumn of 1930 (after many stop-start delays), and then decided that his only concession to the demands of sound cinema would be an original score of his own composition. It was a new delay to the completion of the picture, and a new, artistic and creative distraction for Chaplin himself. It was also the start of a slippery slope, because having decided to add music, he then considered working in some spot sound effects and even little bits of gibberish dialogue for crowd scenes. In fact, his use of a kazoo sound for the speech of the dignitaries was both a dig at such pompous people but also at talking films themselves. He made clever use of a whistle sound, having the Tramp swallow one and so almost ‘talk’ through it. These were all compromises with the way the art of cinema was going, and each of them no doubt struck at Chaplin’s heart, but he was fearful that if he did nothing and simply presented City Lights as a ‘true’ silent picture that audiences, now used to the new world of sound, would simply reject it outright.

Finally, in January 1931, Charlie Chaplin had to put City Lights before the public, and see what would happen. To Henry Bergman he expressed his doubts about the film: ‘I don’t know so much about that picture. I’m not sure.’ All through the making of the film right up to its premiere, Chaplin had been concerned about releasing what was essentially a silent film in the era of sound. Despite his bravado and his bold decision to stick to his artistic guns—silent film was what he knew how to do—there was a worry at the back of his mind that this could be the last film he might ever make.

Chaplin needn’t have worried—the debut screenings of City Lights in Los Angeles (attended by Chaplin’s guest, Albert Einstein) and New York were greeted by standing ovations from appreciative crowds. For many, this new film reminded them of what was possibly being lost in the headlong rush into sound. The filmic art of silent movies was being diminished by the need to put the visuals second to the needs of recorded sound, complete with bulky, immobile cameras that were incapable (initially, at least) of producing the kind of gliding camerawork that featured in F. W. Murnau’s Sunrise (1927) just a few years before.

What Chaplin had achieved with City Lights was a successful combination of some of his most successful shorts (such as The Rounders, 1914, A Night Out, 1915, The Champion, 1915, and The Count, 1916; even, perhaps, 1921’s The Idle Class) with the greater scope of the sort of emotional drama that needed to be central to a feature film. For The New Republic, City Lights was a masterpiece that ‘gave the impression of being created before your eyes, with this extraordinary result.’ For Mordaunt Hall in The New York Times, Chaplin had ‘proved the eloquence of silence’, while for essayist Alexander Woollcott, City Lights was nothing less than ‘a gauntlet thrown down to the rest of Hollywood’ and he labelled Chaplin’s Tramp ‘the finest gentleman of our time’. Variety saw no problem with Chaplin continuing to plow the furrow of silent movies as he was in the unique position of having ‘talent, time, and means’ to produce his films exactly the way he wanted to. For The Record, ‘Nobody in the world but Charlie Chaplin could have done it. He is the only person that has that peculiar something called “audience appeal” in sufficient quantity to defy the popular penchant for pictures that talk. City Lights is the exception that proves the rule.’

What Chaplin had achieved with City Lights was a successful combination of some of his most successful shorts (such as The Rounders, 1914, A Night Out, 1915, The Champion, 1915, and The Count, 1916; even, perhaps, 1921’s The Idle Class) with the greater scope of the sort of emotional drama that needed to be central to a feature film. For The New Republic, City Lights was a masterpiece that ‘gave the impression of being created before your eyes, with this extraordinary result.’ For Mordaunt Hall in The New York Times, Chaplin had ‘proved the eloquence of silence’, while for essayist Alexander Woollcott, City Lights was nothing less than ‘a gauntlet thrown down to the rest of Hollywood’ and he labelled Chaplin’s Tramp ‘the finest gentleman of our time’. Variety saw no problem with Chaplin continuing to plow the furrow of silent movies as he was in the unique position of having ‘talent, time, and means’ to produce his films exactly the way he wanted to. For The Record, ‘Nobody in the world but Charlie Chaplin could have done it. He is the only person that has that peculiar something called “audience appeal” in sufficient quantity to defy the popular penchant for pictures that talk. City Lights is the exception that proves the rule.’

In Britain, Observer critic C. A. Lejeune felt that Chaplin’s work stood tall against the best that European cinema had to offer, citing the work of Rene Clair as comparable. ‘The two directors,’ noted Lejeune of Chaplin and Clair, ‘are almost alone in their power of pure film thinking, without translation through literary or sociological or dramatic idea; they are quite alone in their comic psychology, their sense of the right movement, or pause to reveal the whole mockable nature of man’s soul. Chaplin is the surer artist, giving what Clair has never quite succeeded in suggesting, the sense of frustration behind the laughter; there is always at the back of Chaplin’s work that emotion without logic which first carried him beyond Sennett and the Keystone comedies to be the world’s first clown.’ For critic James Agee (writing in 1950 when the film was re-released), the final scene of City Lights was simply cinematic perfection: ‘The greatest piece of acting and the highest moment in movies.’

City Lights cost Chaplin over $1.5 million to make, a huge sum for a near-silent movie under 90 minutes in length and without any big stars besides Chaplin himself. The average Hollywood feature film in 1930 cost $375,000, suggesting that City Lights cost a whopping four times as much as the average feature. Chaplin’s efforts to recover this expenditure led him into a conflict with United Artists. D. W. Griffith, one of the four original founders, was long gone and the business was now being run by Joseph Schenck, who’d come from the exhibition side into production largely through his wife, actress Norma Talmadge (he would later be a founder of Twentieth Century Pictures and would engineer the merger with the Fox Film Corporation to create 20th Century Fox in 1935). Schenck used United Artist as a vehicle to produce films for his extended family, including wife Norma Talmadge, sister-in-law Constance Talmadge, and brother-in-law Buster Keaton (whom he’d later bring to MGM).

City Lights cost Chaplin over $1.5 million to make, a huge sum for a near-silent movie under 90 minutes in length and without any big stars besides Chaplin himself. The average Hollywood feature film in 1930 cost $375,000, suggesting that City Lights cost a whopping four times as much as the average feature. Chaplin’s efforts to recover this expenditure led him into a conflict with United Artists. D. W. Griffith, one of the four original founders, was long gone and the business was now being run by Joseph Schenck, who’d come from the exhibition side into production largely through his wife, actress Norma Talmadge (he would later be a founder of Twentieth Century Pictures and would engineer the merger with the Fox Film Corporation to create 20th Century Fox in 1935). Schenck used United Artist as a vehicle to produce films for his extended family, including wife Norma Talmadge, sister-in-law Constance Talmadge, and brother-in-law Buster Keaton (whom he’d later bring to MGM).

Chaplin demanded that United Artists pay him fifty per cent of the gross takings of City Lights, a deal far in excess of that offered to any other filmmaker. United Artist’s management were already concerned that Chaplin was putting out an essentially silent movie, when even Fairbanks and Pickford had released a ‘talkie’ film of The Taming of the Shrew in 1929. When they refused his demands, Chaplin decided to distribute City Lights through a ‘roadshow’ method, and charged a higher than usual ticket price of $1.50 (15c higher than regular prices for the new sound films). The film—which took 190 filming days spread over a period of two years and eight months to complete—would go on the gross in excess of $2 million in the US, easily returning Chaplin’s investment; overseas distribution brought in an additional $3 million, making for an overall worldwide gross of $5 million. City Lights remains one of his most successful and most appreciated feature films, and it was Chaplin’s own personal favourite.

Chaplin demanded that United Artists pay him fifty per cent of the gross takings of City Lights, a deal far in excess of that offered to any other filmmaker. United Artist’s management were already concerned that Chaplin was putting out an essentially silent movie, when even Fairbanks and Pickford had released a ‘talkie’ film of The Taming of the Shrew in 1929. When they refused his demands, Chaplin decided to distribute City Lights through a ‘roadshow’ method, and charged a higher than usual ticket price of $1.50 (15c higher than regular prices for the new sound films). The film—which took 190 filming days spread over a period of two years and eight months to complete—would go on the gross in excess of $2 million in the US, easily returning Chaplin’s investment; overseas distribution brought in an additional $3 million, making for an overall worldwide gross of $5 million. City Lights remains one of his most successful and most appreciated feature films, and it was Chaplin’s own personal favourite.

Having succeeded with City Lights, conquering his own fears and bringing his audience along with him, Charlie Chaplin took a break before the next challenge. He left on the ship Mauretania, intending to take time out to visit the London of his boyhood once more. Sitting in his cabin, however, he was plagued with one thought: ‘What am I going do next?’

Trivia: In 1991, the US Library of Congress selected Chaplin’s City Lights for preservation in the National Film Registry, recognising it as ‘culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant’. It is not the only Chaplin film to be so preserved—The Kid (1921), selected in 2011; The Gold Rush (1925), selected in 1992; Modern Times (1936), selected in 1989; and The Great Dictator (1940), selected in 1997, would also make the list.

Charlie Says: ‘Overnight, every theatre began wiring for sound. That was the twilight of silent films. It was a pity, for they were beginning to improve. Murnau, the German director, had used the medium effectively, and some of our American directors were beginning to do the same. A good silent picture had universal appeal both to the intellectual and the rank and file. Now it was all to be lost. I was determined to continue to make silent films, for I believed there was room for all types of entertainment. Besides, I was a pantomimist, and in that medium I was unique and, without false modesty, a master. So I continued with the production of another silent picture, City Lights.’—Charles Chaplin, My Autobiography, 1964.

Charlie Says: ‘Overnight, every theatre began wiring for sound. That was the twilight of silent films. It was a pity, for they were beginning to improve. Murnau, the German director, had used the medium effectively, and some of our American directors were beginning to do the same. A good silent picture had universal appeal both to the intellectual and the rank and file. Now it was all to be lost. I was determined to continue to make silent films, for I believed there was room for all types of entertainment. Besides, I was a pantomimist, and in that medium I was unique and, without false modesty, a master. So I continued with the production of another silent picture, City Lights.’—Charles Chaplin, My Autobiography, 1964.

‘[A] difficulty was to find a girl who could look blind without detracting from her beauty. Virginia Cherrill I had met before … after making one or two tests with other actresses, in sheer desperation I called her up. To my surprise she had the faculty of looking blind. I instructed her to look at me but to look inward and to not see me, and she could do it. Miss Cherrill was beautiful and photogenic, but she had little acting experience. This is sometimes an advantage, especially in silent pictures where technique is all important. Those with less experience are more apt to adapt themselves to the mechanics.’—Charles Chaplin, My Autobiography, 1964.

Verdict: Somewhat episodic and made up of moments Chaplin had explored before in some of his earlier shorts, City Lights is nonetheless a cohesive whole that merges theme and character successfully. Although widely beloved, it’s not my favourite (come back next month for that), but it is easy to appreciate its artistry.

—Brian J. Robb

Next: Modern Times (5 February 1936)

CHARLIE CHAPLIN: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION

An 80,000 word ebook chronicle of Chaplin’s early films from Keystone (1914) and Essanay (1915), based on the first year of blog postings at Chaplin: Film by Film with 20,000 words of supplemental biographical essays.

Also available at Kobo, Nook, Apple, Scribd and other ebook outlets.