Released: 20 November 1915, Essanay

Director: Charlie Chaplin

Writer: Charlie Chaplin

Duration: approx. 24 mins.

With: Edna Purviance, Dee Lampton, Leo White, May White, Bud Jamison

Story: A night at the theatre, disrupted by Mr Pest (in the stalls) and Mr Rowdy (in the gallery).

Production: For the 12th film in his contract with Essanay, Charlie Chaplin opted to rest his Tramp figure that he’d been developing so much in his recent run of shorts, preferring instead to fall back upon another old vaudeville routine, a trusted source which had often formed the inspiration for much of his early film work. Fred Karno’s musical hall sketch ‘Mumming Birds’ had been retitled for touring in the United States as ‘A Night in an English Music Hall’, and it was a variation on the latter title that Chaplin used for this film. Instead of the Tramp, he plays the role of ‘the inebriated swell’, another part he knew very well from countless performances touring the vaudeville stages of Britain and America before he broke into the movies.

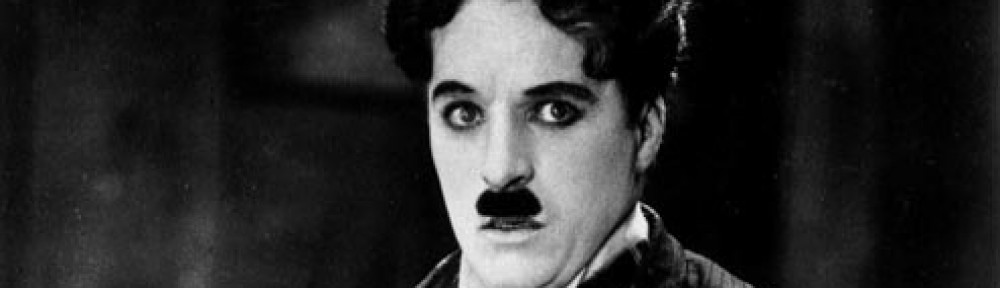

In developing the film version of the Karno original, Chaplin opted to take on two roles: Mr Rowdy, the drunken bum modelled on the original ‘inebriated’ swell, and Mr Pest, also drunk but tuxedo-clad, so filling the ‘swell’ part of the original character. Neither of these is truly the Tramp figure as we’ve come to know him. Mr Pest is dressed for an evening at the theatre, and Chaplin’s slicked down hair emphases his (much noted later) resemblance to Hitler (they were born just four days apart). Mr Rowdy has a bigger moustache than the Tramp, and far baggier pants, but he captures some of the earlier violent physical nature of Chaplin’s original character. The plot is extremely simple, as the two characters Chaplin plays wreak havoc during a vaudeville performance. In this respect, A Night in the Show is perhaps a step back from the detailed character work Chaplin had been doing with his role as the Tramp.

As a fairly faithful filmed version of the Karno sketch, A Night in the Show serves the useful purpose of preserving something of the original vaudeville act. Arguably, though, we don’t see enough of the other (rather terrible) acts on stage, just glimpses of a rotund belly dancer, the comedy singing team of Dot and Dash, a snake charmer, and a fire-eater—all of whom have to struggle on with their performances while Chaplin causes havoc out in the stalls and then on the stage itself. According to Chaplin biographer David Robinson, it was surprising that Chaplin made no formal arrangement with Karno to adapt the material, especially as the old showman was known to jealously guard his intellectual property. Robinson notes that Chaplin expanded the original adding new business that takes place in both the auditorium and the foyer of the theatre, and this may have been enough to distinguish Chaplin’s work from that of Karno (although the remainder is a very faithful version of ‘Mumming Birds’ nonetheless).

It was Chaplin’s performance in the original Karno show that had brought him to the attention of Mack Sennett’s scouts looking for new film talent, so this short was perhaps Chaplin’s attempt to preserve something of the performance that had brought him to film, fame, and fortune in America. Chaplin’s drunk act was justifiably famous, and this short features one of the best examples. As Mr Pest (he’s the main character, with Mr Rowdy little more than a sideshow), he manages to entangle himself with almost everyone else in the vaudeville theatre, from the moment he enters.

A Night in the Show is essentially plotless, comprising a series of simple situations in which Chaplin’s two characters contribute to the spreading of chaos while the performers on stage attempt to get through their routines unscathed (the fire-eater is hosed off, a gag re-used much later in A King on New York, 1957). The well-turned-out Mr Pest is drunk, so seems confused about where he is and what’s going on. From striking his match on an orchestra member’s head to sitting on someone else’s top hat, Mr Pest lives up to his name. When not flirting with the nearest married woman, he’s throwing pies at the performers.

Beyond the silliness, Chaplin is perhaps here making a point about class. As Mr Pest appears well off—he’s dressed in elegant evening clothes and his hair is slicked back—so his antics are tolerated by those around him in a way they would not be if the exact same behaviour had been carried out by his usual Tramp character. This harks back to previous shorts, such as A Jitney Elopement, in which he touched on class difference and sets the stage for later projects like The Count and The Adventurer at Mutual.

Chaplin’s other character is the boorish Mr Rowdy, located in the balcony above the stalls. He spends much time throwing things around, and it is Rowdy who eventually unleashes the fire hose upon the fire-eater. Despite attempting to hide behind a large, theatrical moustache, it is likely that 1915 audiences would have spotted that it was Chaplin playing this larger-than-life second role.

The one who loses out most in A Night in the Show is Chaplin’s leading lady (on and off stage), Edna Purviance. She is the married woman whom Mr Pest flirts with, and that’s all she gets to do in the film. It’s a blink-and-you’ll-miss-her bit, and more could easily have been done with it building upon the pair’s obvious natural chemistry. Perhaps, though, that wasn’t something Chaplin was keen on—the more he got involved with Purviance in real life, the less he seemed to want to feature her in his ‘reel life’ in the film business.

Chaplin would later build upon his dual roles in A Night in Show by repeating the trick to even greater effect in later films The Idle Class (1921) and, most effectively and expansively, The Great Dictator (1940). Drunks, of course, were Chaplin’s stock-in-trade, and would be seen again in The Idle Class and One A.M. (perhaps the pinnacle of his ‘drunk act’ on film).

Chaplin may have been keen to stretch himself beyond the role of the Tramp, even though it was evident from audiences that it was the Tramp they wanted to see. He’d become trapped by the part, and would (with a few exceptions) play it in all of his subsequent films until his later features. The Mutual shorts would allow him to consolidate and perfect the character, while the United Artists features would allow a more in-depth exploration of the ‘little fellow’. However, Chaplin the artist didn’t perhaps achieve proper satisfaction until after The Great Dictator (1940), when he could play other non-Tramp roles in feature films such as in Monsieur Verdoux (1947), in his homage to long-gone vaudeville in Limelight (1952), and in his British film (made in exile from the United States), A King on New York (1957).

By the end of 1915, Charlie Chaplin was arguably the most famous man in the world. Not just the most famous movie star, but also the most famous person. Each new film—and the wait between movies was becoming increasingly longer—was greeted with whoops of joy and applause from ecstatic audiences. The noise, of laughter and clapping, would continue right through the performance, sometimes drowning out the piano musical accompaniment. Charlie Chaplin songs were being sung far and wide, and his image was reaching remote outposts where English was not spoken (not a requirement, as the films were perfectly understandable even without the few inter-title cards used). According to Peter Ackroyd, Chaplin was a figure of fun in Puerto Rico, while in Ghana ‘Fanti savages from Ashanti lands, up-country Kroo boys … Haussas from the north of Nigeria’ all greeted Chaplin with cries of ‘Charlee’ (as reported in The New York Times in 1915).

The merchandising of Chaplin’s image was in full swing as 1915 drew to a close, with dolls, figurines, hats and ties, playing cards, badges and statues widely available. The Tramp character featured in newspaper comic strip series, and the animated cartoon character of Felix the Cat owed more than a little to the antics of the Tramp. There was no escaping Chaplin if you went anywhere near a cinema, where life-size cut out figures and movie posters declared the little Tramp’s presence on the big screen. On stage, you wouldn’t see Chaplin but you could see several prominent imitators (who were also starting to appear on film, much to Chaplin’s understandable fury).

With the ‘great war’ of 1914-1918 underway in Europe, the injured would often recuperate in hospital wards that projected Chaplin’s films as part of the rehabilitation process. It would be a while before Chaplin himself took on the subject of the First World War, most prominently in Shoulder Arms in 1918—he steered clear of the subject as he wasn’t sure it was suitable for humour, but also because his perceived non-participation had brought him great criticism.

One reason Chaplin may have fallen back on reprising an old vaudeville number for A Night in the Show was because he was getting itchy feet once more. As before at Keystone, Chaplin was feeling constrained by Essanay. Although he had a lot of freedom, there was pressure on him to produce more shorts ever quicker, while his developing work habits were taking him in the opposite direction: fewer shorts, but much more thought out in more depth, better character development and better comedy business. It was where his work immediately prior to A Night in Show was heading, and he wanted to work with a management that would give him the time, space, and resources to further develop his art. It was evident that this would not happen at Essanay, and his time with the company was coming to a close.

Trivia: In 1915, it was estimated that Charlie Chaplin’s worldwide audience totalled an astonishing 300 million people of all nationalities speaking a variety of languages. Of his amazing fame, Chaplin said: ‘I am known in parts of the world by people who have never heard of Jesus Christ.’

The Contemporary View: ‘Chaplin loses the rails again by reason of no story … still he is funny. When they showed me this … at times decidedly unpleasant visual narrative, I punctuated it with ribald shouts. I couldn’t help roaring!’—Julia Johnson, Photoplay (1915).

Slapstick: While Mr pest waits patiently behind a statue for a ticket, Mr Rowdy almost takes the first of many near tumbles from the gallery. Seating confusion follows, then a trombone makes for a handy ashtray. A gallery of grotesques in the tiny orchestra pit entrances Mr Pest, leading to conflict with the conductor (and the audience). A latecomer is tipped into the fountain by Mr Pest, who then engages in an arm rest battle with his neighbour. In the gallery, Mr Rowdy pops open a bottle, showering all around (and below) him with the contents. Mr Pest switches seats again, at the cost of two Toppers. There’s more hat trouble when a woman with a giant feathered headpiece positions herself in front of Mr Pest—her feathers are soon plucked. A collision on stage sees Mr Pest come to the rescue. The arrival of a fat boy and his custard pie in Mr Pest’s box leads to… well, you know how that ends (a first for Chaplin?)! Escaped snakes cause new havoc in the orchestra pit and beyond. A firey climax and Mr Rowdy’s hand hose brings down the curtain on the show—even an umbrella can’t save Mr Pest.

Verdict: Standard stuff that was old even 100 years ago, 2/5

Next: Burlesque on Carmen (18 December 1915)

Available Now!

CHARLIE CHAPLIN: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION

An 80,000 word ebook chronicle of Chaplin’s early films from Keystone (1914) and Essanay (1915), based on the blog postings at Chaplin: Film by Film with 20,000 words of supplemental biographical essays.

Pingback: Shanghaied (4 October 1915) | Chaplin: Film by Film

Pingback: One A.M. (7 August 1916) | Chaplin: Film by Film