Release Date: 14 April 1918

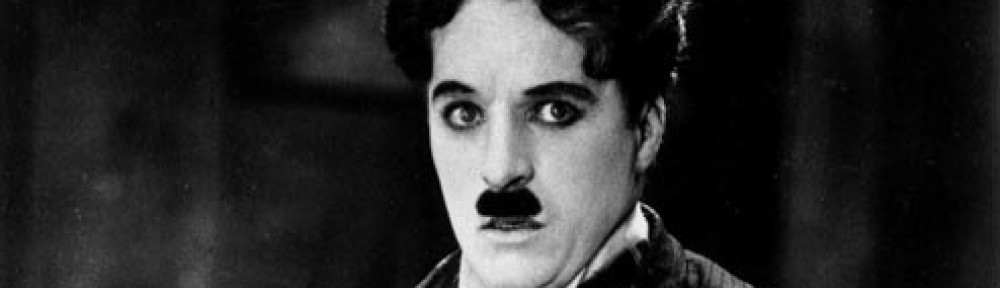

Written and Directed by Charles Chaplin

Duration: 33 mins

With: Edna Purviance (bar singer), Bud Jamison, Albert Austin (pickpockets), Henry Bergman (hot dog vendor/old woman/employment office man), Tom Wilson (policeman), Syd Chaplin (lunch wagon owner), James T. Kelley, Chuck Riesner

Story: The Little Tramp adopts a stray dog (Scraps), falls foul of a couple of pickpockets and some policemen, and falls in love with a singer at a bar…

Production: With The Adventurer, Charlie Chaplin had completed his contract with Mutual. It had taken a bit longer than anticipated, with him producing the work that was initially intended to take one year over a period of more than 18 months. His work rate had slowed considerably since the Keystone days (when he was far from being his own boss), but the quality had arguably improved dramatically. Now without a studio behind him, Chaplin was considering whether to continue with his filmmaking at all—he’d suffered a backlash over his continued avoidance of any involvement in the world war then raging, on behalf of either his birth country of Britain or his adopted home of America. Even then, audiences and studios were reluctant to let Charlie Chaplin vanish entirely.

A five week holiday in Hawaii with Edna Purviance seemed like nothing less than his due reward, but while there Chaplin had to think over the many offers being made to him to continue making movies. The problem was the Charlie Chaplin of late-1917 was very different from the man who’d started in the film business at Keystone under Mack Sennett. Slowly but surely, Chaplin had taken over control of his own output. It was this desire for control and improved films that had caused him to be so slow in fulfilling the terms of the Mutual contract. No matter how it may have irked them, those in charge at Mutual realised that Chaplin was such an asset that he was worth hanging on to, even if they might have to wait a little longer for each film. That was the reason that Mutual were quickest to offer Chaplin a new contract for just eight new movies with a total payment value of $1 million attached, a first in Hollywood.

A five week holiday in Hawaii with Edna Purviance seemed like nothing less than his due reward, but while there Chaplin had to think over the many offers being made to him to continue making movies. The problem was the Charlie Chaplin of late-1917 was very different from the man who’d started in the film business at Keystone under Mack Sennett. Slowly but surely, Chaplin had taken over control of his own output. It was this desire for control and improved films that had caused him to be so slow in fulfilling the terms of the Mutual contract. No matter how it may have irked them, those in charge at Mutual realised that Chaplin was such an asset that he was worth hanging on to, even if they might have to wait a little longer for each film. That was the reason that Mutual were quickest to offer Chaplin a new contract for just eight new movies with a total payment value of $1 million attached, a first in Hollywood.

Chaplin’s half-brother Sydney was his business manager, and he knew that this offer from Mutual would only be the starting point. Other studios were sure to be interested, and Mutual had helpfully established the ‘going rate’ or asking price for Chaplin’s services. Chaplin had also been giving the matter some thought, both during his holiday with Edna and later, upon his return to Los Angeles. The one thing that mattered to him most was control, with the monetary aspects of any new deal of secondary importance. His instruction to Sydney was simple: anything less than total control of his work was unacceptable.

The deal Sydney came back with was with the First National Film Corporation. The company was relatively new having been incorporated in 1917, initially as a theatrical exhibitor and distributor made up of a chain of independent theatre owners across the US, controlling around 600 cinemas. The company had been established to compete with Paramount Pictures (whose Jesse Lasky also bid for Chalpin) that then dominated the distribution of movies (First National would be absorbed by Warner Bros. in 1929). As a relatively new company, First National was keen to make a splash and they did just that by signing both Chaplin and Mary Pickford to $1 million dollar deals. Chaplin’s deal specified he should produce eight films (designated as two-reelers, although each additional reel would bring a further $15,000 in funding), preferably over a period of 18 months but without any firm deadlines attached (he’d end up making just nine movies for First National, mostly three-reelers or longer, but that would take him a total of five years!). His deal promised to deliver to Chaplin an advance of $125,000 on each film, with a split on the profits (after distribution costs) expected to bring his overall earnings across the period of the arrangement to well over the much-publicised $1 million. More importantly, Chaplin would retain copyright ownership of his own films, thus eliminating any further hassles from the likes of Essanay’s George Spoor.

The deal Sydney came back with was with the First National Film Corporation. The company was relatively new having been incorporated in 1917, initially as a theatrical exhibitor and distributor made up of a chain of independent theatre owners across the US, controlling around 600 cinemas. The company had been established to compete with Paramount Pictures (whose Jesse Lasky also bid for Chalpin) that then dominated the distribution of movies (First National would be absorbed by Warner Bros. in 1929). As a relatively new company, First National was keen to make a splash and they did just that by signing both Chaplin and Mary Pickford to $1 million dollar deals. Chaplin’s deal specified he should produce eight films (designated as two-reelers, although each additional reel would bring a further $15,000 in funding), preferably over a period of 18 months but without any firm deadlines attached (he’d end up making just nine movies for First National, mostly three-reelers or longer, but that would take him a total of five years!). His deal promised to deliver to Chaplin an advance of $125,000 on each film, with a split on the profits (after distribution costs) expected to bring his overall earnings across the period of the arrangement to well over the much-publicised $1 million. More importantly, Chaplin would retain copyright ownership of his own films, thus eliminating any further hassles from the likes of Essanay’s George Spoor.

At the same time, Chaplin began work on his own purpose-built studio, where he would be his own producer and have the ability to run his entire production company independently. Although Mutual had repurposed an existing facility for the exclusive use of Charlie Chaplin, the security offered by First National allowed Chaplin to afford to have a dedicated studio purpose-built to his own design. Located on the corner of La Brea Avenue and Sunset Boulevard (about a mile away from the main cluster of studios), the façade of the complex was designed after a row of Tudor-style English cottages, mainly to placate local residents but perhaps also partly intended to appeal to Chaplin’s own English roots. Five acres of former agricultural land (costing Chaplin $34,000) known locally as the R. S. McClellan estate was taken over for the construction of two open-air stages, a host of set building workshops, varied dressing rooms for the performers, a dedicated film laboratory, editing suite and projection room, as well as executive offices and meeting spaces—and a large swimming pool for recreational purposes. Chaplin’s own dedicated office was located in a modest private bungalow on the property. Partly for attractive landscaping purposes, but also calling back to the land’s original use, a series of lemon, orange, and peach trees were maintained within the grounds, as was the 10-room colonial ‘mansion’, the home of the former owner of the orange groves.

At the same time, Chaplin began work on his own purpose-built studio, where he would be his own producer and have the ability to run his entire production company independently. Although Mutual had repurposed an existing facility for the exclusive use of Charlie Chaplin, the security offered by First National allowed Chaplin to afford to have a dedicated studio purpose-built to his own design. Located on the corner of La Brea Avenue and Sunset Boulevard (about a mile away from the main cluster of studios), the façade of the complex was designed after a row of Tudor-style English cottages, mainly to placate local residents but perhaps also partly intended to appeal to Chaplin’s own English roots. Five acres of former agricultural land (costing Chaplin $34,000) known locally as the R. S. McClellan estate was taken over for the construction of two open-air stages, a host of set building workshops, varied dressing rooms for the performers, a dedicated film laboratory, editing suite and projection room, as well as executive offices and meeting spaces—and a large swimming pool for recreational purposes. Chaplin’s own dedicated office was located in a modest private bungalow on the property. Partly for attractive landscaping purposes, but also calling back to the land’s original use, a series of lemon, orange, and peach trees were maintained within the grounds, as was the 10-room colonial ‘mansion’, the home of the former owner of the orange groves.

Construction, by the Milwaukee Building Co. following plans by architects Meyer and Holler (who’d designed the Ince and Goldwyn studios, and would go on to design Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre), cost Chaplin around $100,000. Building commenced in November 1917 and took three months. After Chaplin vacated the studio in 1952 it was used as a location for the William Castle film Hollywood Story and then used or occupied by Stanley Kramer (1954), American International Pictures (1960), Red Skelton (1962), and A&M Records throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Most recently it has been home to the Jim Henson organisation, and the entrance features a statute of Kermit the frog done up as Chaplin’s Little Tramp.

Construction, by the Milwaukee Building Co. following plans by architects Meyer and Holler (who’d designed the Ince and Goldwyn studios, and would go on to design Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre), cost Chaplin around $100,000. Building commenced in November 1917 and took three months. After Chaplin vacated the studio in 1952 it was used as a location for the William Castle film Hollywood Story and then used or occupied by Stanley Kramer (1954), American International Pictures (1960), Red Skelton (1962), and A&M Records throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Most recently it has been home to the Jim Henson organisation, and the entrance features a statute of Kermit the frog done up as Chaplin’s Little Tramp.

Although he began filming on what would ultimately become A Dog’s Life (under the original title I Should Worry) on 15 January 1918, Chaplin officially opened the new studio (located at 1416 N. La Brea Avenue) on 21 January 1918 in front of the waiting press when, in full costume as the Little Tramp, he marked his ‘big shoe’ footprints in wet cement, along with an imprint of his bamboo cane, his name and the date, at the entrance to the studio. It was important that this new environment suit Chaplin, both personally and as a work place in which he would be free to conjure up his new ‘funnies’ in peace and isolation, as it would be where he would be based for the rest of his time working in the United States (essentially until 1952, although he didn’t know that at the time).

Although he began filming on what would ultimately become A Dog’s Life (under the original title I Should Worry) on 15 January 1918, Chaplin officially opened the new studio (located at 1416 N. La Brea Avenue) on 21 January 1918 in front of the waiting press when, in full costume as the Little Tramp, he marked his ‘big shoe’ footprints in wet cement, along with an imprint of his bamboo cane, his name and the date, at the entrance to the studio. It was important that this new environment suit Chaplin, both personally and as a work place in which he would be free to conjure up his new ‘funnies’ in peace and isolation, as it would be where he would be based for the rest of his time working in the United States (essentially until 1952, although he didn’t know that at the time).

Just as everything was going right for Charlie Chaplin towards the end of 1917 in his professional life, things were very different in his private life. He and Edna Purviance had been drifting apart for some time, partly due to his work schedule and their different outlooks on life and ultimate ambitions—she wanted to marry, and Chaplin had no time for that at that moment. Chaplin took time while on that Hawaiian holiday with Edna to give some serious thought to their future together or whether they even had one—his life was about to change in every other way, so was there any reason for his by now unsatisfying life with Edna to persist? The end when it came was down to Edna’s own unfaithfulness, rather than due to any decision of Chaplin’s. In his autobiography Chaplin described himself and Edna as being ‘inseparable’ in 1916, doing everything together, but he was aware of her growing jealousy, not only of the attention paid to him by men and women (due to his increasing fame), but also of his unrelenting dedication to his work.

Just as everything was going right for Charlie Chaplin towards the end of 1917 in his professional life, things were very different in his private life. He and Edna Purviance had been drifting apart for some time, partly due to his work schedule and their different outlooks on life and ultimate ambitions—she wanted to marry, and Chaplin had no time for that at that moment. Chaplin took time while on that Hawaiian holiday with Edna to give some serious thought to their future together or whether they even had one—his life was about to change in every other way, so was there any reason for his by now unsatisfying life with Edna to persist? The end when it came was down to Edna’s own unfaithfulness, rather than due to any decision of Chaplin’s. In his autobiography Chaplin described himself and Edna as being ‘inseparable’ in 1916, doing everything together, but he was aware of her growing jealousy, not only of the attention paid to him by men and women (due to his increasing fame), but also of his unrelenting dedication to his work.

Chaplin was clearly a workaholic and a perfectionist who demanded even higher standards of himself than he demanded of others—this was both a source of great joy to him (he loved his work, even more so the results) but also of great anguish (the work came at a great personal price). Chaplin’s work was the one ‘mistress’ with which Edna Purivance could not complete, and she may have come to feel neglected by Chaplin in favour of his work. Despite this, Chaplin noted: ‘I blamed myself for neglecting her at times.’

Edna had taken up with Thomas Meighan, a film actor 10 years Chaplin’s senior who’d formerly been on the stage and before that was a doctor. When he discovered their liaison, Chaplin was heartbroken. He and Edna split and then reconciled, but when Chaplin found that Edna was still seeing Meighan, he finally put a halt to their relationship. The initial separation affected Chaplin’s creativity and impacted his work, but as time went on it was in his work that he found a new escape: ‘My consolation was in my work.’ Edna’s relationship with Meighan was short; perhaps it had served its purpose in allowing her to find a way away from Chaplin and so to find herself. However, she never married and maintained a collection of press cuttings following Chaplin’s progress. For his part, Chaplin maintained that the time he’d spent with Edna had been the most fulfilling relationship of his early career in films.

Chaplin’s focus on his work in his new environment of his own dedicated studio would serve dividends, but it would take a few years for his creativity to fully blossom. He had been taking steps to develop his filmic storytelling, developing short comedy narratives in new ways in such films as Easy Street and The Immigrant. As part of the First National deal, Sydney had promised that Chaplin would further explore ‘a continuous story’ in each of his future films that at a minimum of three reels each would be longer than any of his previous work. Although Chaplin had produced more story-focused films, he had still built them up from a series of often unrelated comic incidents, only later applying an overall direction to the story (even to the extent of going back and shooting or reshooting material to make his tale more coherent). Now, the plan was for narrative to take precedent over laughs for their own sake—there’d be less slapstick, but more ‘character’ and more emotion in Chaplin’s work. This would begin with his first production for First National, A Dog’s Life.

Chaplin’s focus on his work in his new environment of his own dedicated studio would serve dividends, but it would take a few years for his creativity to fully blossom. He had been taking steps to develop his filmic storytelling, developing short comedy narratives in new ways in such films as Easy Street and The Immigrant. As part of the First National deal, Sydney had promised that Chaplin would further explore ‘a continuous story’ in each of his future films that at a minimum of three reels each would be longer than any of his previous work. Although Chaplin had produced more story-focused films, he had still built them up from a series of often unrelated comic incidents, only later applying an overall direction to the story (even to the extent of going back and shooting or reshooting material to make his tale more coherent). Now, the plan was for narrative to take precedent over laughs for their own sake—there’d be less slapstick, but more ‘character’ and more emotion in Chaplin’s work. This would begin with his first production for First National, A Dog’s Life.

Despite breaking up in real life, Chaplin realised what an asset Edna Purviance was to his movies and they continued to work together for the first three films in his new First National contract—A Dog’s Life, Shoulder Arms (mainly in deleted domestic scenes), and The Pilgrim. In the first of these, A Dog’s Life, Edna plays the bar singer whose emotional laments reduce the bar’s lowlife clientele to tears (Chaplin’s Tramp included), and who reluctantly hustles patrons for dances in order to make them buy more drinks. She’s selective whom she dances with, however, choosing Chaplin’s good natured Tramp over some of the more boorish patrons demanding her attention, a personal discernment that earns her the sack.

Despite breaking up in real life, Chaplin realised what an asset Edna Purviance was to his movies and they continued to work together for the first three films in his new First National contract—A Dog’s Life, Shoulder Arms (mainly in deleted domestic scenes), and The Pilgrim. In the first of these, A Dog’s Life, Edna plays the bar singer whose emotional laments reduce the bar’s lowlife clientele to tears (Chaplin’s Tramp included), and who reluctantly hustles patrons for dances in order to make them buy more drinks. She’s selective whom she dances with, however, choosing Chaplin’s good natured Tramp over some of the more boorish patrons demanding her attention, a personal discernment that earns her the sack.

The film’s other relationship is that between Chaplin’s Little Tramp and the dog, Scraps. The opening sequences in which we find both the Tramp and Scraps getting by separately on the streets set out to compare their lives with one another, giving the film and its title a satirical edge—the Tramp’s life is little better than that of a stray mutt. Both are alone, both suffer the same hunger pangs, and both lose out to the bigger and more ruthless elements within their societies.

The film’s other relationship is that between Chaplin’s Little Tramp and the dog, Scraps. The opening sequences in which we find both the Tramp and Scraps getting by separately on the streets set out to compare their lives with one another, giving the film and its title a satirical edge—the Tramp’s life is little better than that of a stray mutt. Both are alone, both suffer the same hunger pangs, and both lose out to the bigger and more ruthless elements within their societies.

This is depicted when the Tramp attempts to find work at a labour exchange, where his competition with a bunch of other out-of-work men for scarce jobs is contrasted with Scraps conflict with a bunch of larger, wilder dogs on the street over a measly bone. Although the Tramp is first into the exchange, he loses out on a day’s employment as he is continually pushed aside by others or disadvantaged as he attempt to get to one of the open windows before the competition. At the Tramp’s social level, it really is a dog-eat-dog world.

According to Peter Ackroyd’s Chaplin biography, Chaplin had been searching for a suitable animal co-star for a while, realising the emotional screen potential of a teaming of the Tramp with an equally vulnerable creature. A total of 12 (Ackroyd) or 21 (David Robinson) dogs were brought in to the star’s brand new studio to audition for A Dog’s Life, with the winner being a mongrel dubbed ‘Mut’, whose stage and screen name was ‘Scraps’. An accounting entry in the studio ledger is marked ‘whiskey (Mut) – 60 cents’ suggesting the dog may have been given a wee dram or two for the scenes where he was supposed to be asleep or docile, possibly for the scene where the Tramp uses the dog as a makeshift pillow (this kind of practice of sedating a screen animal with alcohol would not be allowed today).

According to Peter Ackroyd’s Chaplin biography, Chaplin had been searching for a suitable animal co-star for a while, realising the emotional screen potential of a teaming of the Tramp with an equally vulnerable creature. A total of 12 (Ackroyd) or 21 (David Robinson) dogs were brought in to the star’s brand new studio to audition for A Dog’s Life, with the winner being a mongrel dubbed ‘Mut’, whose stage and screen name was ‘Scraps’. An accounting entry in the studio ledger is marked ‘whiskey (Mut) – 60 cents’ suggesting the dog may have been given a wee dram or two for the scenes where he was supposed to be asleep or docile, possibly for the scene where the Tramp uses the dog as a makeshift pillow (this kind of practice of sedating a screen animal with alcohol would not be allowed today).

In a news report from 1916, Chaplin was quoted as commenting ‘For a long time I’ve been considering the idea that a good comedy dog would be an asset in some of my plays, and of course the first that was offered [to] me was a dachshund. [It] got on my nerves. The second was a Pomeranian picked up by Miss Purviance. I got sick of having ‘Fluffy Ruffles’ round me, so I traded the ‘Pom’ for Helene Rosson’s poodle. That moon-eyed snuffling little beast lasted two days. What I really want is a mongrel dog. These studio beasts are too well kept.’ Perhaps dogs and Chaplin simply weren’t made for each other—maybe he should’ve tried a kid instead?

In a news report from 1916, Chaplin was quoted as commenting ‘For a long time I’ve been considering the idea that a good comedy dog would be an asset in some of my plays, and of course the first that was offered [to] me was a dachshund. [It] got on my nerves. The second was a Pomeranian picked up by Miss Purviance. I got sick of having ‘Fluffy Ruffles’ round me, so I traded the ‘Pom’ for Helene Rosson’s poodle. That moon-eyed snuffling little beast lasted two days. What I really want is a mongrel dog. These studio beasts are too well kept.’ Perhaps dogs and Chaplin simply weren’t made for each other—maybe he should’ve tried a kid instead?

One brilliant bit of comic business is down to the dog’s tail. Attempting to hide the animal down his trousers as he enters the lowlife bar, Chaplin appears to be sporting a fluffy tail when Scraps own appendage sticks out through a hole in his trousers. Standing by the drummer in the band, the Tramp is oblivious as the dog’s eager wagging tail taps out an unexpected drumbeat, confusing the drummer who’s on a lunch break. Such a gag obviously depends on sound, so seems an odd choice for a silent movie, especially when the choice to add in such sound effects would vary according to each individual exhibitor—for once, the controlling Chaplin couldn’t exactly dictate how that particular gag should be presented.

One brilliant bit of comic business is down to the dog’s tail. Attempting to hide the animal down his trousers as he enters the lowlife bar, Chaplin appears to be sporting a fluffy tail when Scraps own appendage sticks out through a hole in his trousers. Standing by the drummer in the band, the Tramp is oblivious as the dog’s eager wagging tail taps out an unexpected drumbeat, confusing the drummer who’s on a lunch break. Such a gag obviously depends on sound, so seems an odd choice for a silent movie, especially when the choice to add in such sound effects would vary according to each individual exhibitor—for once, the controlling Chaplin couldn’t exactly dictate how that particular gag should be presented.

A Dog’s Life was Chaplin’s longest work to date (apart from his role in Tillie’s Punctured Romance and the expanded Carmen, neither of which he controlled), with filming completed by 22 March (followed by almost a week of intense editing). In expanding his material to three reels (just over 30 minutes in duration), Chaplin faced the task of structuring his narrative in a more disciplined way. While he worked much as he always had in terms of developing comic business within scenes as he went along and as the fancy took him (an approach that was much more tenable in his own studio rather than when under the supervision of others), Chaplin was now finding it necessary to develop at least a modicum of a story spine first from which he could hang his comic business if he were to adequately fill the new running time.

One way of expanding the length of his films was to focus on character. Chaplin’s Tramp had always been at the centre of his films and so had enjoyed greater scope in terms of character development over the years, from the knockabout devil-may-care figure of the Keystone days to the more nuanced and better-developed human being of the Essanay and, especially, the Mutual shorts. Now he turned the character spotlight onto others. Arguably, Edna’s bar singer is a little more developed than some of her past roles, and even the likes of the pickpockets and the lunch wagon vendor get a bit more time and business than might be allowed in a simple two-reeler.

That lunch wagon vendor—from whom the Tramp steals several mouthfuls of muffins (or are they pies? Cakes? Pastries?) before he is caught—was played by Chaplin’s half-brother and business manager Syd Chaplin, the first time the pair had appeared together on screen. They’d worked together on the vaudeville stage, and Syd had been the first of the brothers to be signed up by Fred Karno. Syd effectively replaced Chaplin (upon Chaplin’s recommendation) at Keystone when he left at the end of 1914, but after a year at the studio and little success, Syd left. By then he’d taken up his role as Chaplin’s manager, negotiating both the Mutual and First National contracts that proved to be so lucrative and key to Chaplin’s development as a filmmaker (Syd would later be key to the negotiations that established United Artists in 1919). After appearing beside Chaplin in A Dog’s Life, Syd went on to feature in four more films with him: The Bond, Shoulder Arms, Pay Day, and The Pilgrim. Syd was signed to his own $1 million dollar contract by Famous Players-Lasky, a studio evidently keen to get in on the Chaplin business even if they couldn’t secure the ‘original’ Chaplin.

Syd’s wasn’t the only familiar face to have made the move from Mutual to the First National contract alongside Chaplin. Having essentially established a ‘Mutual repertory group’ that he knew he worked well with, Chaplin saw no reason to rock the boat and signed many of the same performers to work on the First National films as he’d used previously, central to them (for the first trio of films, at least) being Edna Purviance as his ‘leading lady’. Perhaps Chaplin simply knew it might take him a while to find a suitable replacement. Among those who reappeared from the Mutual films were Chaplin’s stand-by Henry Bergman (in at least three roles, and whom Chaplin looked upon as a replacement for the lost Eric Campbell), and the likes of Bud Jamison (from the Essanay days) and Albert Austin (as the pair of pickpockets), James T. Kelley, and Chuck Riesner.

While Chaplin was beginning to develop more complex stories, his camera style remained restrained consisting of largely establishing shots or simple head-on shots of the main characters in any scene. There is little visual innovation or experiment to be discerned from A Dog’s Life, except for the unusual step of shooting Scraps and the other dogs with no or few humans in the scene, following the dog’s adventures in parallel to those of the Tramp (who is endeavouring to ‘liberate’ a hot dog). The Tramp’s attire has been altered slightly; it more ‘vagabond’ in appearance, as he has lost his tie and cane—it is believed that Chaplin dropped the latter due to the need to hold onto the dog’s leash, and also because he was coming to feel he was relying on it a little too much for comic business.

While Chaplin was beginning to develop more complex stories, his camera style remained restrained consisting of largely establishing shots or simple head-on shots of the main characters in any scene. There is little visual innovation or experiment to be discerned from A Dog’s Life, except for the unusual step of shooting Scraps and the other dogs with no or few humans in the scene, following the dog’s adventures in parallel to those of the Tramp (who is endeavouring to ‘liberate’ a hot dog). The Tramp’s attire has been altered slightly; it more ‘vagabond’ in appearance, as he has lost his tie and cane—it is believed that Chaplin dropped the latter due to the need to hold onto the dog’s leash, and also because he was coming to feel he was relying on it a little too much for comic business.

A Dog’s Life ends on an unusual, almost fantasy-like scene of contentment for the Tramp. He’s fulfilled his promise to Edna to move to the country (becoming a farmer in the process, apparently), and seems to have a baby, if the presence of a baby basket is anything to go by. In a final comic upset, we’re shown that the basket contains Scraps and her pups… A family of sorts for Edna and the Little Tramp.

Trivia: The funniest scene in A Dog’s Life comes when the Tramp inserts his arms through a curtain behind the unconscious Albert Austin in an attempt to convince his drinking partner he’s still awake, and in an effort to recover some of the money the pair have stolen (and for the odd sup of beer). This scene (along with a few others in the film) is edited differently in alternate cuts of A Dog’s Life. The film was one of three (the other two being Shoulder Arms and The Pilgrim, along with clips from the incomplete How to Make Movies, see The Bond) were recut and released by Chaplin as The Chaplin Revue in 1959, with a new score composed by Chaplin and his own linking narration. As the original negative of the released version of A Dog’s Life had deteriorated beyond saving by 1940, Chaplin had to rely on alternate takes and unused shots archived by Rollie Totheroh to ‘reconstruct’ the film. Whereas the action in the Revue edit is uninterrupted, the original included reaction shots of Bud Jamison.

Charlie Says: ‘My first picture in my new studio was A Dog’s Life. The story had an element of satire, paralleling the life of a dog with that of the Tramp. This leitmotif was the structure upon which I build sundry gags and slapstick routines. I was beginning to think of comedy in a structural sense, and to become conscious of its architectural form. Each sequence implied the next sequence, all of them relating to the whole. In the Keystone days the Tramp had been freer and less confined to plot. With each succeeding comedy the Tramp was growing more complex. Sentiment was beginning to percolate through the character.’—My Autobiography

Verdict: Chaplin under a new boss (himself!) produces a slight step forward in A Dog’s Life, but it was merely the curtain raiser for the delights yet to come…

—Brian J. Robb

Next: The Bond [29 September 1918]

CHARLIE CHAPLIN: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION

An 80,000 word ebook chronicle of Chaplin’s early films from Keystone (1914) and Essanay (1915), based on the first year of blog postings at Chaplin: Film by Film with 20,000 words of supplemental biographical essays.

Also available at Kobo, Nook, Apple, Scribd and other ebook outlets.