Release Date: 16 April 1917

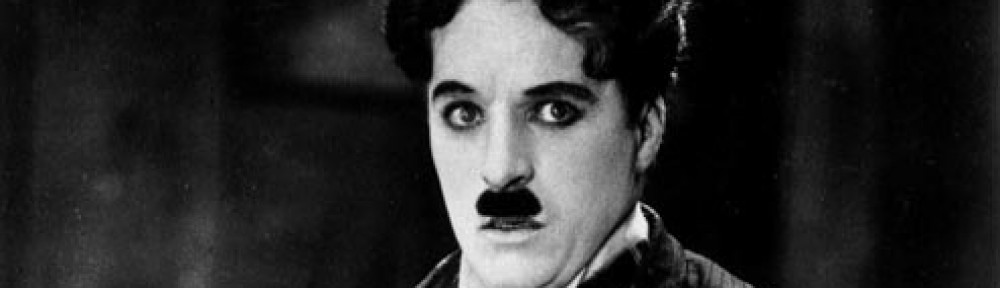

Writer/Director: Charles Chaplin

Duration: 24 mins

With: Edna Purviance, Eric Campbell, Henry Bergman, John Rand, Albert Austin, James T. Kelley, Frank J. Coleman

Story: A drunk (Chaplin) checks into a health spa in order to dry out, but brings a suitcase full of booze with him…

Production: Where Easy Street saw Charlie Chaplin branching out and drawing upon his own childhood experiences of poverty for inspiration, with his next film for Mutual, The Cure, he returned to the tried and tested: his familiar drunk routine. This new spin on a character he’d been playing since his earliest days in vaudeville was his attempt to go straight, even if he turns up at the spa for the cure with a huge trunk full of booze in tow.

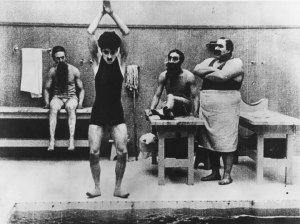

Of course, the humour in such a film comes from the Tramp’s complete resistance to any attempt to sober him up. A relaxing massage turns into a wrestling match, while the Tramp’s supply of back-up booze ends up in the water fountain, leading to all sorts of mayhem. Also in the mix is Eric Campbell’s gout sufferer, ensuring that Charlie gets his sensitive leg stuck in the revolving door, and Edna Purviance needs to be rescued from assorted drunks who’ve partaken of the fountain’s ‘healing’ waters. At the finale, both Charlie and Edna end up in the very same fountain.

The Cure is fast-moving and joke packed, made at a time when Chaplin was in his element, enjoying the security of his Lone Star studio and the complete trust of Mutual, who were resigned to if not relaxed about his slowed pace of production. They knew he’d complete the contracted 10 films, but they perhaps hoped he might have finished before October 1917, when he completed The Adventurer.

Three months had elapsed since the release of Easy Street, a significant period between Chaplin movies. Chaplin’s working process was becoming ever more elaborate and drawn out, as revealed in the Kevin Brownlow/David Gill documentary Unknown Chaplin. Thanks to saved outtakes and unused material, skilfully compiled by Brownlow and Gill, it is possible to witness Chaplin constructing The Cure by shooting, revising, and rethinking individual scenes and scenarios. Spontaneous ideas would mean rearranging or replacing already shot material, while previously discarded notions re-emerge as the work progresses. The opening sequence, for example, was apparently only reached by a total of 84 takes and a rethink in the design of the set.

Three months had elapsed since the release of Easy Street, a significant period between Chaplin movies. Chaplin’s working process was becoming ever more elaborate and drawn out, as revealed in the Kevin Brownlow/David Gill documentary Unknown Chaplin. Thanks to saved outtakes and unused material, skilfully compiled by Brownlow and Gill, it is possible to witness Chaplin constructing The Cure by shooting, revising, and rethinking individual scenes and scenarios. Spontaneous ideas would mean rearranging or replacing already shot material, while previously discarded notions re-emerge as the work progresses. The opening sequence, for example, was apparently only reached by a total of 84 takes and a rethink in the design of the set.

Through the numbered takes we can see Chaplin’s character evolving from bellboy to spa attendant, as the action is relocated from forecourt to the lobby of the health facility. A wheelchair bound patient is initially Eric Campbell, but is then replaced in later takes by Albert Austin. At one point, Chaplin’s employee becomes an ersatz traffic cop, directing the increasing number of wheelchair bound patients.

It is only after 77 takes of various bits of business that Chaplin removes the fountain in the forecourt, replacing it with a more accessible well, so much the better for falling in to. The first drunk to take a dunk is played by John Rand, under Chaplin’s close direction. At some point, whether through frustration or because he couldn’t resist the temptation of the role himself, Chaplin had dropped his previous characters and stepped into the part of the drunk. That led to the revolving door and the emergence of the final version of The Cure as we now know it.

It was little wonder that the progress of each film would be slower and more involved given the way Chaplin was approaching his work. He’d seemingly inherited the idea of starting a film based upon a simple scenario, character or location from Keystone, but on top of that he’d brought his own perfectionist instincts. Having built up a solid reputation for good work in such a short period of time, it is fair to speculate that Chaplin must’ve been terrified of turning in anything less than his best efforts. However, his approach of ‘finding’ the film in the shooting of it was both beneficial and detrimental. A benefit shows up in comic business created accidentally: in one take around the revolving door, Chaplin’s cane gets accidentally caught in the door. A few takes later, he starts to incorporate this ‘accident’ as a deliberate bit of business. This kind of thing would happen a lot as he used time, his colleagues, and reels and reels of film to work out his ideas. The downside was that he could now spend months on each individual film, determined to get it right, constantly striving to improve whatever he’d worked out, only agreeing to release it once his high standards had been satisfied. It certainly worked on the critics, who largely failed to perceive the amount of effort that went in to creating such ‘spontaneity’, such that Motion Picture World was able to say of The Cure: ‘Chaplin’s inimitable expressions and postures are so spontaneous that one cannot for a moment think of his work as preconceived effort.’

It was little wonder that the progress of each film would be slower and more involved given the way Chaplin was approaching his work. He’d seemingly inherited the idea of starting a film based upon a simple scenario, character or location from Keystone, but on top of that he’d brought his own perfectionist instincts. Having built up a solid reputation for good work in such a short period of time, it is fair to speculate that Chaplin must’ve been terrified of turning in anything less than his best efforts. However, his approach of ‘finding’ the film in the shooting of it was both beneficial and detrimental. A benefit shows up in comic business created accidentally: in one take around the revolving door, Chaplin’s cane gets accidentally caught in the door. A few takes later, he starts to incorporate this ‘accident’ as a deliberate bit of business. This kind of thing would happen a lot as he used time, his colleagues, and reels and reels of film to work out his ideas. The downside was that he could now spend months on each individual film, determined to get it right, constantly striving to improve whatever he’d worked out, only agreeing to release it once his high standards had been satisfied. It certainly worked on the critics, who largely failed to perceive the amount of effort that went in to creating such ‘spontaneity’, such that Motion Picture World was able to say of The Cure: ‘Chaplin’s inimitable expressions and postures are so spontaneous that one cannot for a moment think of his work as preconceived effort.’

Simon Louvish, in Chaplin: The Tramp’s Odyssey, positions The Cure as a kind of sequel to One A.M., working on the assumption that the character of ‘Mr. Arthur Arkwright, the naturalist’ may be the same drunk audiences saw struggling with the contents of his home when he arrived back late one night slightly the worse for wear. Perhaps, so Louvish’s theory goes, The Cure sees the same character presenting himself for detoxification. According to Louvish, ‘The Cure is a torture chamber of society’s solutions for the demon rum’s malignant authority… The revolving door exemplifies [the] failed attempt at moral resurrection … There is no cure for society’s ills, as it is incurably insane.’

Simon Louvish, in Chaplin: The Tramp’s Odyssey, positions The Cure as a kind of sequel to One A.M., working on the assumption that the character of ‘Mr. Arthur Arkwright, the naturalist’ may be the same drunk audiences saw struggling with the contents of his home when he arrived back late one night slightly the worse for wear. Perhaps, so Louvish’s theory goes, The Cure sees the same character presenting himself for detoxification. According to Louvish, ‘The Cure is a torture chamber of society’s solutions for the demon rum’s malignant authority… The revolving door exemplifies [the] failed attempt at moral resurrection … There is no cure for society’s ills, as it is incurably insane.’

Was Chaplin’s approach to filmmaking at this stage an example of his growing abilities as an artist, creating the films with the camera as an author writes with a pen (or typewriter), being willing to discard what doesn’t work, to rework material, or even drop everything in order to start again? Or was it, as Chaplin biographer Joyce Milton suggests, simply symptomatic of a man who couldn’t make up his mind? It took Chaplin four months to complete and release The Cure, and while the final film is regarded as one of his best, the increasing delays and slowing pace of production was of concern to Mutual, who felt their ‘Lone Star’ was perhaps delaying production for no very good reason (except, maybe, his own enrichment).

Milton reports that Chaplin was becoming ever more moody during this time, and had a tendency to upset those he was working with, perhaps simply a symptom of his own artistic frustration in making The Cure. A new recruit among Chaplin’s company during the early part of 1917 was his new personal publicist, Carlyle T. Robinson, who would remain by the comedian’s side for the next decade and a half. Robinson quickly found that Chaplin ‘was a very difficult person to meet, even within his own studio. I learned also that it was absolutely forbidden for strangers to penetrate into the studio, that the star did not like journalists, and did not wish to be bothered by old friends, even those who had known Charlie Chaplin when he played in the English music halls.’

Robinson quickly got the measure of his new employer, learning his ways. It was clear that Chaplin did not keep anything resembling ‘office hours’, and would come and go from the studio at all hours of the day and night, as inspiration or the need to work struck him. Robinson was to be on the receiving end of Chaplin’s eccentricities and idiosyncrasies, as well as his strongly expressed likes and dislikes. According to Robinson, Chaplin’s favourites, like Henry Bergman, tended to be disliked by the rest of the crew working on the Chaplin films, simply because they’d been singled out for the star’s favour.

For all its inventiveness, there is something basic about The Cure. The scenario is not particularly unique, while the comic business featuring Chaplin’s drunk and Eric Campbell’s gout-struck foot is par for the course. Even the negligent romance with Edna is underplayed, except for one surprising moment that sticks out today. As noted by John Kimber in The Art of Charlie Chaplin, ‘[Charlie and Eric]’s routine feuding over Edna is enlivened by a moment when Charlie imagines that Eric’s salacious invitations are being directed at him, and reacts with a mixture of embarrassment and pleasure.’

For all its inventiveness, there is something basic about The Cure. The scenario is not particularly unique, while the comic business featuring Chaplin’s drunk and Eric Campbell’s gout-struck foot is par for the course. Even the negligent romance with Edna is underplayed, except for one surprising moment that sticks out today. As noted by John Kimber in The Art of Charlie Chaplin, ‘[Charlie and Eric]’s routine feuding over Edna is enlivened by a moment when Charlie imagines that Eric’s salacious invitations are being directed at him, and reacts with a mixture of embarrassment and pleasure.’

Chaplin’s focus on the mischief making drunk is a throwback to his earlier Keystone shorts in which the Tramp was the source of most of the mayhem that ensued. In The Cure he has retreated from being the figure of authority seen in his policeman in Easy Street, bringing order where there is chaos, and has instead returned to playing the Trickster figure, the one who causes the chaos where there otherwise was order.—Brian J. Robb

Charlie Says: ‘When I see a screen actress get ready to cry, I look the other way until she’s through with the spasm. It gives me the shudders; I feel ashamed. That isn’t good acting. Some directors insist on their actresses crying during certain kinds of emotional scenes. Then they show a close-up of tears furrowing through make-up. Uhh! One of the easiest things in acting is to bring tears. I can do it any time, but I should never forgive myself if I had some scene like that photographed.’—New York Tribune Sunday, 30 December 1917

Trivia: Chaplin’s astonishing earnings at Mutual [see Chaplin Signs With Mutual] had been causing consternation through 1916 and 1917 in the motion picture community, with many arguing that his payment was ridiculously high at a time of war when many people were struggling to earn a decent income. Photoplay magazine ran an article entitled ‘C. Chaplin, Millionaire-Elect’ that focused on Chaplin’s accumulating wealth. Photoplay noted that ‘Except for John Hayes Hammond, President of US Steel, ‘Chaplin’s salary is likely the biggest salary grabbed off by any public person outside of royalty.’ Statistics revealed that Chaplin’s salary made up 17 per cent of the total salaries paid to 96 Senators and 435 Representatives of the US Congress, and 93 per cent of the Senate’s payroll.

The Contemporary View: ‘If there should be any impression that Charlie Chaplin has slipped the slightest in his ability to comically mime in the films, the once over of his latest effort, The Cure (Mutual), should certainly “cure” any such idea. … It may be that Chaplin fans will vote The Cure the best of the Mutual’s so far. It has been […] months since the previous Chaplin, Easy Street, was released, and therefore the new one is considerably late. A reason for that probably is the rather pretentious hotel setting employed, which looked good enough to have taken plenty of time for construction. … The Cure is a whole meal of laughs, not merely giggles, and ought to again emphasize the fact that Charlie is in a class by himself.’—Variety, 13 April 1917

‘[The Cure] wherein Charlie Chaplin proves himself a great comedian. There is little slapstick comedy used in this burlesque on sanatorium life. Chaplin’s inimitable expressions and postures are so spontaneous that one cannot for a moment think of his work as preconceived effort. It is interesting to note that of each of Mr. Chaplin’s latest comedies one feels like saying: “the best yet”.’—Motion Picture Magazine, July 1917

Verdict: One of the best Mutuals, even if Chaplin’s character reverts to near-Keystone type as the creator of chaos.

Next: The Immigrant (17 June 197)

CHARLIE CHAPLIN: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION

An 80,000 word ebook chronicle of Chaplin’s early films from Keystone (1914) and Essanay (1915), based on the blog postings at Chaplin: Film by Film with 20,000 words of supplemental biographical essays.

Also available at Kobo, Nook, Apple, Scribd and other ebook outlets.