Release Date: 22 January 1917

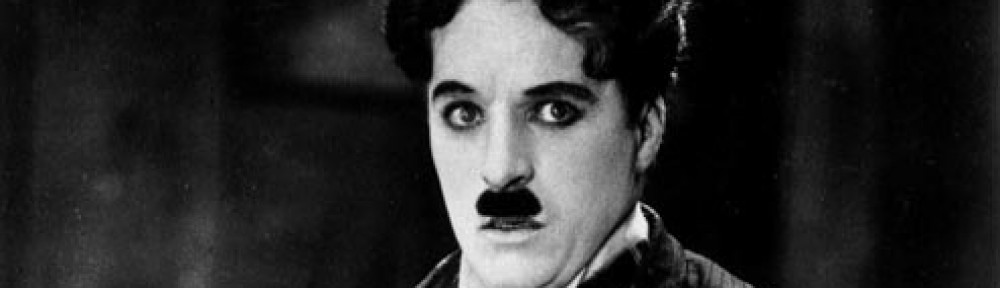

Writer/Director: Charles Chaplin

Duration: 23 mins

With: Edna Purviance, Eric Campbell, Albert Austin, James T. Kelley, Henry Bergman

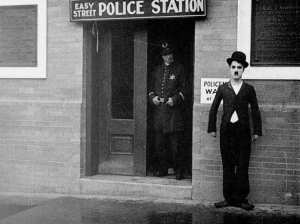

Story: The Tramp arrives on Easy Street, where a visit to the local Mission leads him to join the police and tackle the local bully (Eric Campbell) to restore order.

Production: During 1917 Charlie Chaplin would complete his contract with Mutual by producing four more films: Easy Street, The Cure, The Immigrant, and The Adventurer. To one degree or another, all four are widely regarded as being amongst Chaplin’s finest work.

For his first film of 1917, Chaplin turned to his own childhood experience, with a dash of the Karno sketch ‘Early Birds’ thrown in. The idea for a comedy set among the people of the slums had come to Chaplin while he was editing Behind the Screen, and he immediately commissioned the construction of one of his most elaborate sets yet. Easy Street would see the building of the first of several T-shaped street scenes (devised by set designer Danny Hall), within which his drama could play out. This one cost the studio about $10,000 to construct and was bigger than the elaborate set previously employed for the department store in The Floorwalker.

For Chaplin biographer David Robinson, this huge set ‘has the unmistakable look of South London’ (where Chaplin grew up in poverty). Wrote Robinson in 1985, ‘Even today, Methley Street, where Hannah Chaplin [Charlie’s mother] and her younger son lodged, between Hayward’s pickle factory and the slaughterhouse, presents the same arrested vista, the cross-bar of the “T” leading to the grimier mysteries on either side.’

According to Peter Ackroyd’s Chaplin biography, the comedian’s inspiration came from East Street in Walworth, where he believed he had been born. Quite why Chaplin should have been contemplating his urban origins in 1917 isn’t entirely clear. To this point, his Tramp persona had largely existed in the new American city (with the occasional rural outing). Now, he was journeying back beyond even the old Karno sketches that he’d recently drawn on for The Rink or in One A.M. to his own childhood experiences in turn-of-the-century London for inspiration.

Easy Street was one of Chaplin’s few Mutual outings in which he actually played a straightforward version of his Tramp character. His depiction in the opening minutes sees the Tramp at his most pathetic, curled up and destitute outside the Hope Mission. Lured inside by the sound of song, he witnesses a preacher’s sermon and is taken with the preacher’s daughter (Edna Purviance). Undergoing something of an instant transformation, the Tramp returns the collection box he’d stolen and hidden under his threadbare jacket. Easy Street was, as Robinson noted, ‘a comic parody of Victorian “reformation” melodramas’.

Easy Street was one of Chaplin’s few Mutual outings in which he actually played a straightforward version of his Tramp character. His depiction in the opening minutes sees the Tramp at his most pathetic, curled up and destitute outside the Hope Mission. Lured inside by the sound of song, he witnesses a preacher’s sermon and is taken with the preacher’s daughter (Edna Purviance). Undergoing something of an instant transformation, the Tramp returns the collection box he’d stolen and hidden under his threadbare jacket. Easy Street was, as Robinson noted, ‘a comic parody of Victorian “reformation” melodramas’.

Chaplin takes things further than this simple story. Arriving on Easy Street, the now reformed Tramp comes upon a recruitment poster for the police and in an unlikely development, he quickly signs up. His move from wastrel to productive member of society (indeed, a figure of authority) is complete. Unfortunately he’s unaware of the high turn over of police officers in the area as they are ‘hauled away to the hospital hourly’, as John McCabe puts it in his Chaplin biography.

Now sporting a British policeman’s uniform that is naturally a size (or two!) too large for him (and with his helmet habitually on backwards), the Tramp returns to Easy Street, looking impose law and order on the unruly area which seems to be in a permanent condition of riot. Almost immediately he falls foul of the local bully, giant Eric Campbell, against whom a mere truncheon is ineffective. Rather than tackle the big fella himself, he puts in a call to the station for back up. Here, Chaplin once more engages in his comedy of transformation, trying to deceive Campbell by pretending the phone is in fact a musical instrument and then a telescope.

Now sporting a British policeman’s uniform that is naturally a size (or two!) too large for him (and with his helmet habitually on backwards), the Tramp returns to Easy Street, looking impose law and order on the unruly area which seems to be in a permanent condition of riot. Almost immediately he falls foul of the local bully, giant Eric Campbell, against whom a mere truncheon is ineffective. Rather than tackle the big fella himself, he puts in a call to the station for back up. Here, Chaplin once more engages in his comedy of transformation, trying to deceive Campbell by pretending the phone is in fact a musical instrument and then a telescope.

The most famous scenes of Easy Street involve Chaplin, Campbell and a street lamp. As the bully displays his strength by bending the lamp over, the Tramp manages to trap the bully’s head within the top of the lamp fitting and then uses the free-flowing gas supply to knock him out. The lampposts had proved problematic during the December 2016 shoot on Easy Street. They were made to be easy enough for Campbell to bend, but supposedly were strong enough to stand upright themselves. Instead, at least one of the lamps bent without any force being applied, only to hit Chaplin in the face, injuring his nose and delaying filming for a few days as he couldn’t wear his Tramp make-up and moustache (which a baby in the earlier mission scenes had previously grabbed off his face).

The most famous scenes of Easy Street involve Chaplin, Campbell and a street lamp. As the bully displays his strength by bending the lamp over, the Tramp manages to trap the bully’s head within the top of the lamp fitting and then uses the free-flowing gas supply to knock him out. The lampposts had proved problematic during the December 2016 shoot on Easy Street. They were made to be easy enough for Campbell to bend, but supposedly were strong enough to stand upright themselves. Instead, at least one of the lamps bent without any force being applied, only to hit Chaplin in the face, injuring his nose and delaying filming for a few days as he couldn’t wear his Tramp make-up and moustache (which a baby in the earlier mission scenes had previously grabbed off his face).

Simon Louvish, in his book Chaplin: The Tramp’s Odyssey, describes Chaplin’s lone cop as ‘all of Keystone rolled into one uniform’. It is his task to succeed where the rest of the force has failed, in taking down Campbell’s neighbourhood bully a peg or two. Of course, this capture is only temporary, as awakening in the police station Campbell’s force of nature soon breaks out, wrecking the station in the process. Chaplin’s policeman is only able to finally defeat the bully once and for all by dropping a cast iron stove on his head. He then has to rescue Edna from the hostile crowd, conjure up the strength when he accidentally sits upon a drug addicts needle, and—as Joyce Milton puts it in her book, Tramp—‘the cocaine cocktail works miracles’. It’s an odd development, out of keeping with the rest of the film.

Simon Louvish, in his book Chaplin: The Tramp’s Odyssey, describes Chaplin’s lone cop as ‘all of Keystone rolled into one uniform’. It is his task to succeed where the rest of the force has failed, in taking down Campbell’s neighbourhood bully a peg or two. Of course, this capture is only temporary, as awakening in the police station Campbell’s force of nature soon breaks out, wrecking the station in the process. Chaplin’s policeman is only able to finally defeat the bully once and for all by dropping a cast iron stove on his head. He then has to rescue Edna from the hostile crowd, conjure up the strength when he accidentally sits upon a drug addicts needle, and—as Joyce Milton puts it in her book, Tramp—‘the cocaine cocktail works miracles’. It’s an odd development, out of keeping with the rest of the film.

Although Chaplin had slowed his production process quite a bit by 1917, certainly when compared to the breakneck pace at Keystone three years before, Mutual were anxious enough about the slow progress of Easy Street to issue a statement to the film trade. The delay was attributed to ‘the unusual character of the latest Charlie Chaplin production … involving so many big scenes which, while they appear to be “interiors” are exteriors, necessitating sun for their success.’ That winter had been unusually wet in California, making work on the open air Chaplin sets difficult at times. Chaplin, the Mutual statement went on, preferred ‘to delay completion of the comedy until conditions for its successful filming are perfect.’

Easy Street is one of the few Chaplin films to feature young children—in one scene where the Tramp policeman is dispensing food to impoverished children, he does it as though he were scattering grain to chickens. Much later, Chaplin explained to Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein that the scene communicated his own dislike of children. Eisenstein was reported to have not been surprised at this revelation: after all, he explained, the only people who do not like children are other children, thereby casually labelling Chaplin as either infantile or child-like. Another whom the comedian told of his dislike of children was English author Thomas Burke. Some felt this was because children may have intimidated the comedian. Chaplin saw in children his most astute critics, not yet cursed by self-awareness but attuned to detect insincerity on behalf of posturing adults. [See Trivia].

As he had done in the past, Easy Street saw Chaplin trying to perfect something he’d explored in a previous film. Chaplin had laid the groundwork for Easy Street in Police (belated released in May 1916 after he’d left Essanay; see Chaplin: A Centenary Celebration for full coverage), made between The Bank and A Night in the Show. At that same time, Chaplin had been working on a project tentatively titled Life (again, see Chaplin: A Centenary Celebration), a film he ultimately left incomplete, with Essanay incorporating some footage into Police (and Triple Trouble, 1918).

Life was both Charlie Chaplin’s first attempted feature film and his first abandoned project. It was also intended to be Chaplin’s first fusion of comedy and tragedy, a difficult mix he wouldn’t really get to grips with in any serious way until these later films at Mutual. Intended to address the serious issue of urban poverty, a pressing issue at the time, Chaplin conceived of a sharply satirical, yet serious film that would be feature-length and would examine the lives lead by those at the bottom of society: the down-and-outs, the drunks, the ne’er-do-wells, even the Tramps. This ambition would find further expression in Easy Street.

In Charlie Chaplin and His Times, author Kenneth S. Lynn notes of Life: ‘The flophouse nightmare came straight out of Chaplin’s childhood experience—but not in a direct way. … For marginal people who have experienced status loss, there is always the fear of the abyss beneath them, as well as a compulsion to keep up appearances, to dress respectably, to speak properly. … In the Life fragments, the satirical savagery of Chaplin’s presentation of the poor devils in a squalid flophouse leaves little doubt that he had a horror of such people.’

Chaplin combined this with the idea of him playing a policeman, lifting the focus on law and order from 1916’s Police. Full of social commentary, Police was an indicator of the kind of depth Chaplin would bring to his work at Mutual. The combination of the examination of impoverished lives planned for Life with the role of the authority figure of the policeman from Police is what makes Easy Street so memorable among Chaplin’s Mutual output. The contrast between his slight figure of law and order with Campbell’s giant of an anarchic bully, together with the iconic location and setting, make for a more memorable short than most.

Chaplin combined this with the idea of him playing a policeman, lifting the focus on law and order from 1916’s Police. Full of social commentary, Police was an indicator of the kind of depth Chaplin would bring to his work at Mutual. The combination of the examination of impoverished lives planned for Life with the role of the authority figure of the policeman from Police is what makes Easy Street so memorable among Chaplin’s Mutual output. The contrast between his slight figure of law and order with Campbell’s giant of an anarchic bully, together with the iconic location and setting, make for a more memorable short than most.

Nonetheless, there is a moral ambiguity in Chaplin’s figure of triumphant authority. He is ‘converted’ from outlaw Tramp to productive citizen by his visit to the Hope Mission, as much by the beauty of Edna Purviance as anything the minister might impart. Once he resolves to join the police, he moves from lawbreaker to enforcer, although he carries out his duties within his own moral framework. Rather than arresting a woman who steals bread, he helps her (by stealing more supplies) after hearing her story of impoverishment (on the other hand, he arrests a man who simply laughs at his outsized uniform). He follows in the path Edna laid before him, one of bringing relief and aid to others. That, as much as anything else, motivates his drive to rescue her from ruffians at the climax.

Nonetheless, there is a moral ambiguity in Chaplin’s figure of triumphant authority. He is ‘converted’ from outlaw Tramp to productive citizen by his visit to the Hope Mission, as much by the beauty of Edna Purviance as anything the minister might impart. Once he resolves to join the police, he moves from lawbreaker to enforcer, although he carries out his duties within his own moral framework. Rather than arresting a woman who steals bread, he helps her (by stealing more supplies) after hearing her story of impoverishment (on the other hand, he arrests a man who simply laughs at his outsized uniform). He follows in the path Edna laid before him, one of bringing relief and aid to others. That, as much as anything else, motivates his drive to rescue her from ruffians at the climax.

In a curious way, Easy Street looks forward to The Pilgrim (First National, February 1923). Where both Easy Street’s predecessor Police and this film feature sanctimonious preachers whose words help move Chaplin’s Tramp in the ‘right’ direction, by the time of The Pilgrim, he himself has become the preacher figure (albeit in disguise), imparting wisdom to others. It was perhaps based upon a transformation Chaplin himself had undergone, during his time in the United States, from inexperienced newcomer to global superstar, able to dictate his own destiny.

Given that Chaplin is often accused of sentimentality in his filmmaking (something that increased over time), it is perhaps surprising how unsentimental is the depiction of the poor and impoverished in Easy Street. Perhaps this comes from the ‘Early Bird’ Karno sketch upon which Chaplin was drawing, with its depiction of ‘the gruesome jollity of English poverty, wretchedness and crime’. The sketch even included the central conflict of Easy Street between the youthful defender of the street’s put-upon inhabitants and ‘the brutal, remorseless “rough”’ who is ultimately tamed by the use of a table as a weapon (in the original sketch, an oven in Easy Street).

The entire film can be read as a kind of wish fulfilment for Chaplin, the (albeit on screen) realisation of a dream he had harboured since his own impoverished childhood. Chaplin’s brave cop is the one to restore order to the lawless streets, turning even Campbell’s bully and his wife into productive, well-behaved members of wider society. It is the triumph of order over chaos, of control over anarchy. This is not the creed of the Tramp, who spreads chaos wherever he goes, but of Easy Street’s reformed cop, who bests the bully and (in the spirit of Victorian charity) distributes food to needy children. It is an oddly different take on things than Chaplin normally presented in his comedy. At the end, a final title card proclaims: ‘Love backed by force, forgiveness sweet / Brings hope and peace, to Easy Street’. The question is whether this was Chaplin’s message, or simply the one he thought his audience expected to hear, especially during a time of war.—Brian J. Robb

The entire film can be read as a kind of wish fulfilment for Chaplin, the (albeit on screen) realisation of a dream he had harboured since his own impoverished childhood. Chaplin’s brave cop is the one to restore order to the lawless streets, turning even Campbell’s bully and his wife into productive, well-behaved members of wider society. It is the triumph of order over chaos, of control over anarchy. This is not the creed of the Tramp, who spreads chaos wherever he goes, but of Easy Street’s reformed cop, who bests the bully and (in the spirit of Victorian charity) distributes food to needy children. It is an oddly different take on things than Chaplin normally presented in his comedy. At the end, a final title card proclaims: ‘Love backed by force, forgiveness sweet / Brings hope and peace, to Easy Street’. The question is whether this was Chaplin’s message, or simply the one he thought his audience expected to hear, especially during a time of war.—Brian J. Robb

Charlie Says: ‘If there is one human type more than any other that the whole wide world has it in for, it is the policeman type. Of course, the policeman isn’t really to blame for the public prejudice against his uniform—it’s just the natural human revulsion against any sort of authority. Just the same, everybody loves to see the “copper” get it where the chicken got the axe. … The natural supposition is that the policeman is going to get the worst of it and there is intense interest in how I am to come out of my apparently unequal combat with “bully” Campbell.’

Trivia: Chaplin admitted to an uneasiness working with (or even simply being around) children, but this didn’t stop him (or his studio publicist) from using them to promote the movie. A statement was issued to the press that highlighted the fact that Chaplin did not like to see children being exploited by being put to work, even if it was by him at his studio. He’d seen enough of such things during his London childhood. Therefore, according to the reports, he instructed the children working on Easy Street to ‘play your favourite games. I will pay you for playing, not working.’ He later explained more in an interview, highlighting his own childhood experiences and recounting how at the age of six the poor financial and physical situation of his mother forced him onto the variety stage. The report noted that ‘conditions were not so favourable then as now, and Charlie looks back with horror on the late hours he had to keep to earn just a few shillings weekly.’

The Contemporary View: ‘In Easy Street, Charlie Chaplin supplies the Mutual [sic] with the two reeler that is almost a month late in release, but, it is said, from the fact that a lamp-post fell and marred the nose of the comic, forcing him to “lay off” for two weeks. There is a lamp-post used in Easy Street, and in the action it is bent and broken so that the alibi for the delay seems correct. Perhaps for the first time since he started with Mutual. Chaplin portrays a policeman … the resultant chaos and the several new stunts will be bound to bring the laughter and the star’s display of agility and acrobatics approaches some of the Doug Fairbanks pranks. Chaplin has always been throwing things in his films, but when he “eases” a cook stove out of the window onto the head of his adversary, on the street below, that pleasant little bouquet adds a new act to his repertory. Easy Street certainly has some rough work in it—maybe a bit rougher than the others—but it is the kind of stuff that Chaplin fans love. In fact, few who see Easy Street will fail to be furnished with hearty laughter.’—Variety, 2 February 1917

‘In Easy Street, Charlie Chaplin’s latest and best, if we may venture to obtrude so decided an opinion, an original key has been struck. At any rate, it is Chaplin at his funniest; and nothing much more entertaining, by way of comedy, could be imagined than his adventures with the street bully, when on occasion he has been placed on patrol duty in wild and woolly Easy Street, after having changed his profession from tramp to policeman. … With all this excellence of entertaining quality, the picture presented a couple of points which would require elimination. One of these occurs in the suggestive handling of an overturned baby’s bottle in one of the scenes in the East Street mission, and the other where the dope fiend makes too free use of the needle in one of the Easy Street tenements.’—Moving Picture World, 17 February 1917

Verdict: One of Chaplin’s most memorable outings, as much for the clash between his diminutive policeman and Eric Campbell’s outsized bully.

Next: The Cure (16 April 1917)

Available Now!

CHARLIE CHAPLIN: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION

An 80,000 word ebook chronicle of Chaplin’s early films from Keystone (1914) and Essanay (1915), based on the blog postings at Chaplin: Film by Film with 20,000 words of supplemental biographical essays.

Also available at Kobo, Nook, Apple, Scribd and other ebook outlets.