Released: 21 December 1914, Keystone

Director: Mack Sennett

Writer: Mack Sennett

Duration: 74 mins (six reels)/85 mins (2003 restoration)

With: Marie Dressler, Charlie Chaplin, Mabel Normand, Chester Conklin, Mack Swain, The Keystone Kops, Charles Bennett, Charley Chase

Story: World-weary city man (Chaplin) meets fresh, innocent country girl (Dressler), and plots to get his hands on her father’s fortune…

Production: Widely regarded as the first proper ‘feature length’ comedy film made in Hollywood, Tillie’s Puncture Romance was created by Mack Sennett as a vehicle for stage actress Marie Dressler. If she’s recalled at all these days, it is more likely to be for her acerbic role in the brilliant Dinner at Eight (1933), co-starring Jean Harlow. Before 1914, the Canadian-born Dressler was a theatre and vaudeville veteran taking her first steps in the new-fangled world of movies. That Sennett built his film around the mis-cast Dressler and not his newest native movie star Charlie Chaplin betrays something of the projects lengthy and tortured gestation.

Sennett’s Keystone was only two years old when he embarked upon his first feature film production, inspired by news that his one-time mentor D.W. Griffith was working on a similarly lengthy project then called ‘The Clansman’ (later released as Birth of a Nation). Sennett employed most of his regular Keystone players in roles in the film, with Chaplin and Mabel Normand at the top of the list. The film, was, however, expressly designed to launch the then 44-year-old Dressler as a movie star. Sennett called her ‘a star whose name and face meant something to every possible theatre-goer in the United States and the British Empire.’ The project started shooting in April 1914, before Chaplin’s astonishing star status was fully established. Sennett feared that his regular Keystone performers, even Normand, would not automatically command theatre bookings, so he was relying on Dressler as a ‘known name’ to attract an audience. By the time the film was released at the very end of 1914, the audience were coming for Chaplin not to see some stage actress, although—as we’ll see—Chaplin wasn’t exactly playing his Tramp character.

Sennett secured Dressler for the film on a twelve week contract, paying her $2,500 per week. The film was based upon the musical play Tillie’s Nightmare by Edgar Smith with which Dressler had enjoyed some success on stage in 1910 (and she’d revive the production in 1920). Filming filled 45 working days across eight weeks, and the production had wrapped by June. All the while, the Sennett crew were continuing to produce their regular shorts. Sennett recalled: ‘I had to continue the steady flow of short comedies each week. This meant that I never had my Tillie cast all working together on any given day. One or two of them were constantly out of the picture acting in a two reeler.’

The film had a budget of $50,000, well in excess of the cost of six single-reelers. In fact, while Tillie’s Punctured Romance was in production Chaplin featured in no less than five other shorts: The Fatal Mallet, The Knockout, Her Friend the Bandit, Mabel’s Busy Day, and Mabel’s Married Life. That’s another reason why he wasn’t the star of the show: he had too many other Keystone commitments to be released to work solely on the feature film.

Dressler’s career was suffering one of it’s regular downturns, so the offer to star in a film couldn’t have come at a better time (she’d made two previous film appearances but as herself; Tillie’s Punctured Romance would be her first on screen performance as a fictional character). According to Glenn Mitchell in The Chaplin Encyclopedia, Dressler showed a great deal of business sense in organising distribution of the film through her husband’s company (this proved problematic later when distribution was actually handled by the Alco Film Company instead) and in claiming a co-ownership in the film itself. It was Keystone’s writer (or ‘scenario editor’, as they were then known) Craig Hutchinson who suggested filming the play that had brought Dressler great success, a notion no doubt welcomed by the actress as an opportunity to revisit past glories.

Sennett was determined to make a big success of America’s first feature length comedy film, but wanted to focus more on the character of Tillie rather than in making a straight adaptation of Tillie’s Nightmare. Every resource his studio had was put in service of the film, with production weaving in and out of the studio’s regular output. It wasn’t an easy task as Dressler, more used to the environment of the stage, found it difficult to adapt to the techniques of film acting, something that Charlie Chaplin had quickly grasped instinctively. He was, in fact, in the process of pioneering a whole new approach to screen acting, something Dressler seems to have failed to grasp. The film was promoted as ‘The Impossible Attained: a SIX REEL comedy!’

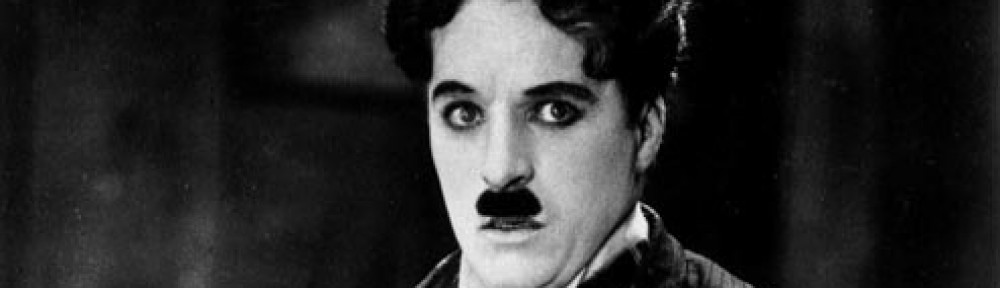

Playing a ‘city slicker’ type villain in a standard, if over long, Keystone caper probably did not appeal to Chaplin at this point. This film was made just as he was beginning to develop his Tramp character in new ways, taking ever more control of his own projects. Now, he was playing second fiddle to a theatre ‘star’ who employed the standard neo-Victorian over-emotive screen acting previously used by Ford Sterling (long gone from Keystone by this point). Under the direction of Mack Sennett, Mabel Normand’s role (she gets a significant close-up) was probably considered of more importance than Chaplin’s moustache twirler (his two piece minimalist moustache is not long enough for him to actually twirl it, nor is it full enough to hide his youth). It would be the last time (apart from guest appearances) that Chaplin would appear in a movie under someone else’s direction.

Even more irritating to Chaplin may have been Dressler’s later claim (in her own unreliable memoirs) to have ‘discovered’ the screen comedian. ‘I went up on the [Keystone] lot and I looked around until I found Charlie Chaplin who was then unknown,’ she said of beginning work on Tillie’s Punctured Romance. ‘I picked him out and also Mabel Normand. I think the public will agree that I am a good picker for it was the first real chance Charlie Chaplin ever had.’

The film’s theatrical origins are occasionally painfully obvious: it is split into six acts, separated by title cards. The opening sees Dressler appear in front of a curtain apparently as herself, before the scene dissolves to show her in character (a theatrical curtain also closes the film, and the principals, including Chaplin, take their bows). Despite being middle-aged, Dressler portrays Tillie as a ‘girl’ who quickly falls for Chaplin’s city slicker, although he’s only interested in her as a way to access the family fortune. He convinces the love-struck Tillie to elope with him and escape her abusive father, kicking off a series of adventures as the country ‘girl’ encounters city life. Cars and clothes give her problems, as does her new-love’s unexpected girlfriend (Normand). Plying Tillie with drink, Chaplin and Normand make off with her purse, buying themselves new clothes while Tillie deals with the law. After a brief stay with her uncle, Tillie finds herself homeless and penniless, finally winning a job at a local cafe. At the movies, Chaplin and Normand see a film in which a thief gets his just deserts. Feeling guilty, they track down Tillie—but learning of the family fortune they hatch a new plan. Much chaos follows, especially during a sequence set at a society ball in which Tillie pelts Charlie with ornaments and finally shoots off a pistol wildly in his direction. Tillie is then disenfranchised, so she pursues Chaplin and Normand, still waving the gun, and chase is soon joined by the Keystone Kops. Inevitably, in the way of Sennett and Keystone, several major players end up running off the end of the pier and splashing into the water. By the end, Tillie and Mabel are friends, and both turn their backs on the city slicker.

Chaplin’s character resembles more some of the earlier non-Tramp roles he played, people who have fallen low in society and are simply out for themselves. There’s enough comedy here, though, to make up for the absence of the Tramp character. His seduction of Tillie is well-done. Chaplin’s biographer David Robinson saw hints of a much later character in Chaplin’s performance here: ‘At moments, Chaplin’s characterisation of the deft, funny, heartless adventurer anticipates Verdoux, even though Verdoux could never insult the footmen and an effeminate guest at a party as Chaplin does.’ Robinson also noted that the screen experience of both Chaplin and Normand put them in a different league to Dressler whose ‘warm personality wins through’ nonetheless. Indeed, of the trio it was Normand who had the most film experience in front and behind the camera.

When the finished film was screened at a trade show on 14 November 1914 (ads began appearing in the press during the previous week), it was Chaplin rather than Dressler who found himself the centre of attention. When the film had been completed in the summer, Chaplin’s star was only just beginning to rise. Now, as the year was coming to a close, he’d become the most famous screen personality on the planet, and his services were much in demand. It was Chaplin, too, who drew comment from the critics. ‘Chaplin outdoes Chaplin,’ wrote Moving Picture World of Tillie’s Punctured Romance. ‘That’s all there is to it. His marvellous right-footed skid … is just as funny in the last reel as it is in the first.’ While Variety rightly highlighted Dressler as the film’s putative star, their correspondent went on to note that ‘Chaplin’s antics are an essential feature in putting the picture over.’ While his supporting role was seen as essential to the film’s success. It wasn’t a production that Chaplin thought much of. ‘It was pleasant working with Marie,’ he wrote in My Autobiography, ‘but I did not think that the picture had much merit. I was more than happy to get back to directing myself.’ While Sennett was hailed for his groundbreaking move in producing the first comedy feature film, Chaplin had outgrown the Keystone way of making movies and was ready to further develop his craft elsewhere. Many kicks up the backside were to follow.

Slapstick: A brick tossed by ‘the girl’ knocks ‘the stranger’ to the ground—that’s a 1914 example of cinematic ‘meet cute’. The pair then play footsie. However, courting proves painful for the city swell. Traffic proves a baffling obstacle for the ‘country girl’ in the big city, as does alcohol. There’s a lovely Tramp-style foot skid as Chaplin and Normand exit the cafe having stolen the country girl’s purse. At the police station, she drunkenly puts the bite on the desk sergeant. Chaplin has his usual trouble with swing doors as he enters the clothes store. Chaplin doesn’t appreciate the musical accompaniment to the film-within-the-film, nor the appearance of his analogue on screen. The reveal of Charley Chase’s lawman badge (he’s sitting next to them in the cinema) is the final straw… When the girl recognises Chaplin in the cafe he gets a face full of food and makes a swift exit. In attempting to get to the new heiress first, Chaplin has to navigate a wet floor, with inevitable consequences. High society proves to be physically challenging for the new groom (and for new servant Mabel), especially on the dance floor. A run-in with Chester Conklin’s party guest unleashes the usual Keystone tit-for-tat slaps and punches. A follow-up encounter sees punches thrown around the punch bowl. Chaplin struts his stuff on and off the dance floor with Marie, while Mabel drains the punch bowl. Cakes then a gun are Marie’s weapons of choice when she discovers Charlie and Mabel in a clinch, kicking off the long-time-coming climatic chase sequence. Charlie and Mabel exit, pursued by a bear, sorry, by Marie Dressler. A footman calls the Keystone Kops, who chase everyone off the end of the pier.

Verdict: The ultimate Keystone-Mack Sennett movie, for good or ill… 3/5

Available Now!

CHARLIE CHAPLIN: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION

An 80,000 word ebook chronicle of Chaplin’s early films from Keystone (1914) and Essanay (1915), based on the blog postings at Chaplin: Film by Film with 20,000 words of supplemental biographical essays.