Released: 27 April 1914, Keystone

Released: 27 April 1914, Keystone

Director: Mabel Normand

Writers: Mabel Normand, Charlie Chaplin

Duration: approx. 22 mins (two reels)

With: Mabel Normand, Harry McCoy, Chester Conklin, Edgar Kennedy, Minta Durfee

Story: A waiter (Chaplin) takes on the role of a foreign dignitary to impress a girl (Normand), only to be invited to a society garden party…

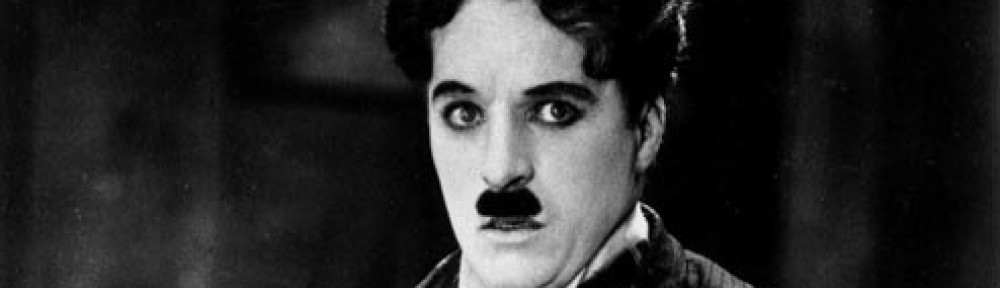

Production: Over the final weeks of April and the first few weeks of May 1914, Charlie Chaplin would more-or-less alternate between appearing in standard Keystone efforts churned out by either Mabel Normand or Mack Sennett and movies where he came up with the original scenario and took charge of how it would be staged. In some cases the difference between Chaplin in the regular Keystone shorts and the tentative steps he begins to take controlling his own material are like night and day.

Caught in a Cabaret is very much a bog-standard Normand/Sennett effort, with Chaplin straight-jacketed into playing a Keystone character any number of clowns could fulfil. There is some evidence, though, to suggest that Chaplin was having an effect on the work of those who employed him—remember, he was the ‘new boy’ and had only been at Keystone and even making films for a few months at this stage, although it is likely he didn’t think much of the even-at-this-point cliched pie throwing that features towards the end of Caught in a Cabaret: Mabel gets it in the kisser.

In his charade as a high-flying foreign dignitary (Baron Doobugle, Prime Minister of Greenland, according to a close up of his business card), it is possible to see some of the seeds of themes and issues that Chaplin would explore in more depth in his later work, such as class difference, something that wasn’t supposed to exist in America but which Chaplin was all too aware of from his lowly London origins. Elements from Caught in a Cabaret would be replayed in much of Chaplin’s later work, including in The Count, The Rink (both 1916), The Idle Class (1921), and in one of his mature films, Modern Times (1936). There’s some business with a dog sidekick in Caught in a Cabaret as well which looks forward to Chaplin’s pooch pals in Champion (1915) and A Dog’s Life (1918), although here his dachshund is little more than another prop. It’s the first film in which Chaplin’s Tramp has a regular job, and features him in various confrontations with his boss (larger than him) and a co-worker (who is much smaller), setting up contrasts of scale that would reoccur in later movies.

Chaplin’s clearly in command of his own performance here, and when he’s off-screen he is sorely missed. It’s evident just from the way he walks, puts on his hat and jacket, and the way he tips his hat in the street that he knows his Tramp character inside and out. The waddle as he walks, the skidding around corners, the fading gentility—it is all part of a distinctive character unlike any seen in movies before, and although it would be developed and changed over time, Chaplin had hit upon the basic core of his Tramp character this early in his cinematic work. His hero moment with a mallet where he evicts a surly bar patron is a nice touch, but it feels like it is from a completely different story (The Fatal Mallet, 1914, perhaps?) than the one this movie, as Normand no doubt originally conceived it, is trying to tell.

Done up in a more presentable frock coat and top hat ensemble, Chaplin’s Tramp arrives at Mabel’s garden party, where he is quickly the centre of attention and begins drinking the place dry. A return visit by Mabel and her coterie of debutant friends (engineered by her jealous boyfriend who’d earlier followed him to his workplace) reveals Charlie’s fraud and leads to the riotous climax. It was clear that in working together on Caught in a Cabaret, whatever the dynamics of the power relations within Keystone, that Chaplin and Normand had reached an accommodation with one another. In classic form, the result of all this industry would be a future in which Chaplin would triumph and Normand would fall, as scandals and ill-health plagued her until her early death at the age of 37 in 1930.

Slapstick: A swing door (a consistent inanimate adversary across several films, which he appears to have mastered by the end of this one) and some spilled food gives Charlie the waiter some trouble right at the start, and he (briefly) loses his little dog when he gets tangled up in its lead. There’s plenty of falling about when he sees off a ruffian who is bothering Mabel, while her boyfriend stands by doing nothing. A brick in the face and a slap from Mabel both put Chaplin on the floor at the film’s end.

Verdict: Some interesting moments and further signs of the progress to come, but not exceptional, 3/5

Next: Caught in the Rain (4 May 1914)

Available Now!

CHARLIE CHAPLIN: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION

An 80,000 word ebook chronicle of Chaplin’s early films from Keystone (1914) and Essanay (1915), based on the blog postings at Chaplin: Film by Film with 20,000 words of supplemental biographical essays.

Pingback: Chaplin at 100: Mid to Late March and April | Memoirs of a Mangy Loner

Pingback: Caught in the Rain (4 May 1914) | Chaplin: Film by Film

Pingback: Her Friend the Bandit (4 June 1914) | Chaplin: Film by Film

Pingback: The Knockout (11 June 1914) | Chaplin: Film by Film

Pingback: The Face on the Bar Room Floor (10 August 1914) | Chaplin: Film by Film

Pingback: A Jitney Elopement (1 April 1915) | Chaplin: Film by Film

Pingback: Twenty Minutes of Love (20 April 2014) | Chaplin: Film by Film

Pingback: The Count (4 September 1916) | Chaplin: Film by Film