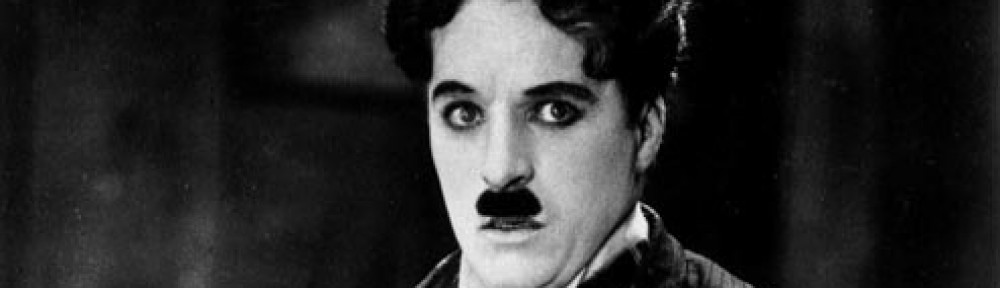

In early 1919, Charlie Chaplin joined with three other film business luminaries—Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and D. W. Griffith—to set up a new studio that would be driven by the creative talents who made the films. United Artists was born, and although it has endured years of turmoil, it is still around today almost 100 years later.

The first Hollywood studio established by the creative talent, rather than businessmen or mogul investors, was United Artists, launched on 5 February 1919. The founders of the newest Hollywood studio were Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, then two of the movie world’s biggest names, director D. W. Griffith and… Charlie Chaplin!

Chaplin had opened his own new physical studio space just a year before in January 1918 in order to fulfil his contract with First National. Since then, he’d released only three films—A Dog’s Life and his first near-feature length film Shoulder Arms, as well as the liberty bond supporting propaganda film The Bond. It was during his tour of major cities of the US selling war bonds to the public that the idea of establishing a new co-operative studio had come up in Chaplin’s discussions with Pickford and Fairbanks.

By this point in the schedule he’d agreed with First National, Chaplin was supposed to have delivered a total of eight films. He’d grown uneasy with the studio’s complaints about his tardiness, claiming the company was ‘inconsiderate, unsympathetic, and short-sighted’, which Chaplin biographer Peter Ackroyd interpreted as meaning ‘they refused to comply with all of his demands’. First National seemed unimpressed with both A Dog’s Life and Shoulder Arms, despite the fact that both films were instantly profitable, and seemed only concerned with the fact that Chaplin still owed the company five further films. Even though he had his own studio, Chaplin still felt he was under the control of his financiers. It is little wonder he was attracted to the utopian idea of total independence that he’d discussed with Pickford and Fairbanks.

By this point in the schedule he’d agreed with First National, Chaplin was supposed to have delivered a total of eight films. He’d grown uneasy with the studio’s complaints about his tardiness, claiming the company was ‘inconsiderate, unsympathetic, and short-sighted’, which Chaplin biographer Peter Ackroyd interpreted as meaning ‘they refused to comply with all of his demands’. First National seemed unimpressed with both A Dog’s Life and Shoulder Arms, despite the fact that both films were instantly profitable, and seemed only concerned with the fact that Chaplin still owed the company five further films. Even though he had his own studio, Chaplin still felt he was under the control of his financiers. It is little wonder he was attracted to the utopian idea of total independence that he’d discussed with Pickford and Fairbanks.

The new studio would be run by the filmmakers, allowing them to indulge their creativity without being beholden to distant management figures who knew nothing of their art but who only cared about the bottom line. That was the idealistic intent, at least. Establishing the studio as a kind of artists’ collective would mean all those principally involved would invest their own money, be responsible for producing their own films, and then control the distribution of those films to audiences. In their minds, this would mean true independence.

As Chaplin biographer David Robinson notes in Chaplin: His Life and Art, the concept of United Artists was ‘revolutionary. Until this time producers and distributors—with the exception of First National— had been employers, and the stars salaried employees. Now the stars became their own employers. They were their own financiers, and they received the profits that had hitherto gone to their employers.’

As well as the four already named, early discussions of what was to become United Artists involved cowboy film star and director William S. Hart, but he soon dropped out have negotiated better terms with his studio. The remaining four talents incorporated their venture with them each holding a 25 per cent share of the preferred shares in the company, while the common shares where distributed among them at the rate of 20 per cent each, with the final 20 per cent of common shares going to the company’s lawyer, William Gibbs McAdoo. He had been Secretary to the Treasury under President Woodrow Wilson (also his father-in-law) until the end of 1918 and had recently established his own law firm, McAdoo, Cotton & Franklin. The idea of being in on the birth of a new Hollywood film studio was attractive to McAdoo, and he stayed with the organisation until 1922 when he left to re-establish his political career.

As well as the four already named, early discussions of what was to become United Artists involved cowboy film star and director William S. Hart, but he soon dropped out have negotiated better terms with his studio. The remaining four talents incorporated their venture with them each holding a 25 per cent share of the preferred shares in the company, while the common shares where distributed among them at the rate of 20 per cent each, with the final 20 per cent of common shares going to the company’s lawyer, William Gibbs McAdoo. He had been Secretary to the Treasury under President Woodrow Wilson (also his father-in-law) until the end of 1918 and had recently established his own law firm, McAdoo, Cotton & Franklin. The idea of being in on the birth of a new Hollywood film studio was attractive to McAdoo, and he stayed with the organisation until 1922 when he left to re-establish his political career.

Taking Over the Asylum

The plan for the new venture had come about just at a time when the management of Hollywood’s nascent studios were attempting greater control over the ‘talent’ who actually made the pictures. What would become known as the classic ‘studio system’ that worked so well in the 1930s and 1940s was slowly beginning to form through a series of company mergers, but the stars who set up United Artists wanted to forge their own creative paths. Richard A. Rowland, head of Metro Pictures (later part of the MGM conglomerate), is said to have uttered the legendary lament ‘The inmates are taking over the asylum’ when he heard of the plans for United Artists.

With Hiram Abrams (formerly a board member and president at Paramount) as the first managing director, United Artists opened an office at 729 Seventh Avenue in New York. The stars may have been a little premature in establishing their own concern, however. The agreement called for each of the stars to produce, through United Artists, five movies each year—however, almost all of them had current outstanding commitments to various studios, including Chaplin who still owed First National those other five films on his contract. Given that Chaplin’s rate of production had dramatically slowed in recent years, how he ever thought he could hold up his end of the bargain and produce five movies each year is a mystery.

Chaplin wanted to produce better work, and increasing the quality of his films meant increasing their costs. He’d said of the successful Shoulder Arms, ‘the film had taken longer than anticipated, besides costing more than A Dog’s Life’. Now he hoped that First National would agree to increase funding for his films in return for an improvement in their quality. However, when the idea was put to the First National board of directors, they turned Chaplin down. It seemed to them that quality, strictly speaking, was immaterial, as almost anything with the ‘Charlie Chaplin’ name on it would attract a willing, paying audience. They simply wanted Chaplin to complete the five films he owed them.

Chaplin wanted to produce better work, and increasing the quality of his films meant increasing their costs. He’d said of the successful Shoulder Arms, ‘the film had taken longer than anticipated, besides costing more than A Dog’s Life’. Now he hoped that First National would agree to increase funding for his films in return for an improvement in their quality. However, when the idea was put to the First National board of directors, they turned Chaplin down. It seemed to them that quality, strictly speaking, was immaterial, as almost anything with the ‘Charlie Chaplin’ name on it would attract a willing, paying audience. They simply wanted Chaplin to complete the five films he owed them.

Chaplin attempted to turn the tables on the studio, suggesting he could produce the pictures he owed them quickly, ‘if that is the kind of pictures you want’, meaning they’d be quickly made, cheap and cheerful, and of lesser quality. According to Chaplin’s autobiography, his blackmail gambit backfired when the board told him, ‘that’s up to you, Charlie.’ He attempted one last time to win their favour: ‘I’m asking for an increase to keep up the standard of my work. Your indifference shows your lack of psychology and foresight. You’re not dealing with sausages, you know, but with individual enthusiasm.’

It was to no avail. As far as the suits at First National were concerned, the Charlie Chaplin films may have well have been sausages—they were simply ‘product’ created in order that they could make a profit, what that product was seemed to be immaterial. It is little wonder that when the idea of United Artists became more fully developed, Chaplin couldn’t wait to joining Griffith, Pickford, and Fairbanks in forging their independence from Hollywood’s indifferent and grasping management.

The Early Years

By the time United Artists actually started producing material it was 1921 and the film world had changed. Shorts, the kind of film that Charlie Chaplin had thrived in, were on their way out to be replaced by eight-reel (about 90 minutes) feature films that were more expensive to produce and becoming increasingly star-studded. In the light of that, the five films each year commitment of the founders was quietly abandoned.

The first United Artists film to see release was written by and starred Douglas Fairbanks. Largely forgotten now, His Majesty, the American was a comedy hit that featured future Frankenstein actor Boris Karloff in a small uncredited role as ‘the spy’. Over the first five years of its existence, United Artists only released five films, at an average rate of a single film each year, all a far cry from the founders’ original ambitions.

Where was Chaplin in all this? Well, for a while he was busy fulfilling his outstanding obligation to First National. Those films included 1921’s The Kid, often considered to be Chaplin’s first true feature film (it’s about 20 minutes longer than Shoulder Arms). He didn’t complete the First National contract until 1923 with the release of The Pilgrim, Chaplin’s final short and the last film he co-starred in with Edna Purviance (although she would play the lead in A Woman of Paris, which Chaplin directed but did not star in beyond a brief cameo).

Where was Chaplin in all this? Well, for a while he was busy fulfilling his outstanding obligation to First National. Those films included 1921’s The Kid, often considered to be Chaplin’s first true feature film (it’s about 20 minutes longer than Shoulder Arms). He didn’t complete the First National contract until 1923 with the release of The Pilgrim, Chaplin’s final short and the last film he co-starred in with Edna Purviance (although she would play the lead in A Woman of Paris, which Chaplin directed but did not star in beyond a brief cameo).

Chaplin’s first film for United Artists was probably not what his co-founders expected. Instead of a laugh-packed comedy featuring the Little Tramp, he offered them Destiny, later titled A Woman of Paris, a melodrama he would direct but would not star in. Part of Chaplin’s aim was to offer a showcase to former girlfriend Edna Purviance, in the hope that she could be launched into a film career away from his own films. Purviance plays the mistress of a wealthy Parisian businessman (played by Adolphe Menjou; this film helped give him a higher profile, less so for Purviance who only made two further films before retiring) who reconnects with her aspiring artist former boyfriend (Carl Miller), leading to a tragic denouement. Chaplin appeared uncredited and out of his Tramp outfit as a station porter, and his frequent co-star Henry Bergman has a small bit as a headwaiter.

Each member of the United Artists collective were free to pursue their own creative muse free from the impositions of the others, but there must’ve been some disquiet from the other three that they were going to release a Chaplin picture without Charlie Chaplin in it. In the event, Mary Pickford loved the movie. ‘A Woman of Paris allows us to think for ourselves and does not constantly underestimate our intelligence,’ she said. ‘It is a gripping human story throughout and the director allows the situations to play themselves. Charlie Chaplin is the greatest director of the screen. He’s a pioneer. How he knows women!—oh, how he knows women! I do not cry easily when seeing a picture, but after seeing Charlie’s A Woman of Paris I was all choked up.’

Artists Disunited

By 1924, director D. W. Griffith had left the United Artists set-up, while producer Joseph Schenck joined as president with a remit to put the company on a more professional filmmaking footing. He came with some additional value baggage, namely his wife movie star Norma Talmadge, her sister Constance Talmadge, and third Talmadge sister Natalie’s husband, comedian Buster Keaton. From 1926’s The General, United Artists handled the distribution of Keaton’s comedies until he returned to MGM (with Schenck) with 1928’s The Cameraman. Schenck also succeeded in bring in various independent producers, including Samuel Goldwyn and Howard Hughes, to work with United Artists. Schenck also established a separate deal with Chaplin and Pickford to own theatres across the US. By 1935, Schenck had left to created 20th Century Fox, merging his own 20th Century Pictures with the Fox Film Corporation. Throughout the 1930s, other producers continued to use United Artists as a distributor, including Walt Disney Pictures, Hal Roach Studios (home of Laurel and Hardy), David O. Selznick, Walter Wanger, and Alexander Korda.

By 1924, director D. W. Griffith had left the United Artists set-up, while producer Joseph Schenck joined as president with a remit to put the company on a more professional filmmaking footing. He came with some additional value baggage, namely his wife movie star Norma Talmadge, her sister Constance Talmadge, and third Talmadge sister Natalie’s husband, comedian Buster Keaton. From 1926’s The General, United Artists handled the distribution of Keaton’s comedies until he returned to MGM (with Schenck) with 1928’s The Cameraman. Schenck also succeeded in bring in various independent producers, including Samuel Goldwyn and Howard Hughes, to work with United Artists. Schenck also established a separate deal with Chaplin and Pickford to own theatres across the US. By 1935, Schenck had left to created 20th Century Fox, merging his own 20th Century Pictures with the Fox Film Corporation. Throughout the 1930s, other producers continued to use United Artists as a distributor, including Walt Disney Pictures, Hal Roach Studios (home of Laurel and Hardy), David O. Selznick, Walter Wanger, and Alexander Korda.

Chaplin released most of his features through United Artists, from 1925’s The Gold Rush, The Circus (1928), City Lights (1931), and Modern Times (1936)—all largely silent pictures. Three ‘talkies’—The Great Dictator (1940), Monsieur Verdoux (1947), and Limelight (1952)—were all released by United Artists, although Limelight was pulled from theatres shortly after release when Chaplin was forced into political exile in the UK and Switzerland. His final two features, A King in New York (1957) and A Countess From Hong Kong (1967), were made in exile in London.

Douglas Fairbanks died in 1939 and United Artists entered something of a decline in the 1940s. The movie business was changing and independent producers were finding it hard to compete with the ‘big seven’ studios. This situation would only begin to change with the 1948 ‘Paramount Decree’ that forced studios to sell their theatres, thus opening them up to independently produced films.

Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin were the only original founders still involved in United Artists as the 1950s dawned. In 1951, producers Arthur B. Krim and Robert Benjamin were put in charge of United Artists, with a remit to run the company successfully for ten years—at the end of that period, if the studio was profitable, they would take a half ownership. Immediate hits included The African Queen (1951) and High Noon (1951), but it was all too late for Chaplin, who was forced into political exile when his permit for re-entry to the United States was revoked in September 1952. In 1955, Chaplin—now based in Switzerland—cut his final business ties with the US by selling his 25 per cent share in United Artists to Krim and Benjamin for just over $1 million. A year later, Mary Pickford also sold up for $3 million. By 1957, United Artists went public, selling shares worth $17 million. The company was now producing around 50 films each year. None of the original founders were involved.

Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin were the only original founders still involved in United Artists as the 1950s dawned. In 1951, producers Arthur B. Krim and Robert Benjamin were put in charge of United Artists, with a remit to run the company successfully for ten years—at the end of that period, if the studio was profitable, they would take a half ownership. Immediate hits included The African Queen (1951) and High Noon (1951), but it was all too late for Chaplin, who was forced into political exile when his permit for re-entry to the United States was revoked in September 1952. In 1955, Chaplin—now based in Switzerland—cut his final business ties with the US by selling his 25 per cent share in United Artists to Krim and Benjamin for just over $1 million. A year later, Mary Pickford also sold up for $3 million. By 1957, United Artists went public, selling shares worth $17 million. The company was now producing around 50 films each year. None of the original founders were involved.

For the next 50 years United Artists would undergo a complicated history of take-overs (the TransAmerica Corporation in 1967, Ted Turner in 1986 for about five minutes), mergers (in 1980, when Kirk Kerkorian’s MGM joined United Artists to form MGM/UA Entertainment), asset stripping (Ted Turner again, throughout the 1980s), and near-bankruptcies. Along the way, the studio would move into records and television, and at one point owned 50 per cent of the James Bond franchise. By 2006, Tom Cruise became a partial owner of United Artists for a couple of years, before MGM once again fully took over the studio in 2015. Today United Artists continues as a brand name for the in-house material MGM produces and distributes.

It is all a long way from when back in 1919 Charlie Chaplin and three friends established United Artists as a place to be owned and operated by the creative talent that actually makes movies. However, despite all the turmoil the studio endured over the years, surely Chaplin (who died in 1977) would have been happy to know that the studio he helped found is still going strong almost 100 years later.

Charlie Says: ‘Within six months, Mary [Pickford} and Douglas {Fairbanks] were making pictures for the newly formed company [United Artists], but I still had more comedies to complete for First National. As Mary and Doug were the only stars distributing their pictures through our company, they were continually complaining to me of the burden imposed upon them as a result of being without my product. [This] ran the company into a deficit of $1 million. However, with the release of my first film [for United Artists], The Gold Rush, the debt was wiped out, which rather softened Mary and Doug’s grievances, and they never complained again.’—Charlie Chaplin, My Autobiography [1964]

—Brian J. Robb

Next: Sunnyside (15 May 1919)

Available Now!

CHARLIE CHAPLIN: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION

An 80,000 word ebook chronicle of Chaplin’s early films from Keystone (1914) and Essanay (1915), based on the blog postings at Chaplin: Film by Film with 20,000 words of supplemental biographical essays.

Documentary: Star Power—The Creation of United Artists